In Central Oregon “there just isn’t enough water to go around.” Managers, users and enviros must hash out tough compromises

Intractable? In Jefferson County, the North Unit Irrigation District is a part of a consortium of eight irrigation districts and municipalities that collaborate on critical issues facing Central Oregon water users. Photo: NUID

By Kendra Chamberlain. March 30, 2023. Farmers in Central Oregon are looking at another bad water year.

The Deschutes river basin is entering its fourth year of drought and as snowpacks have failed to materialize over the last few winters, both farmers and wildlife are struggling to survive.

“I’ve seen—since 2019—this downward trend in our water supply,” says Mike Britton, executive manager of the North Unit Irrigation District in Madras. “The last four or five years are what we consider dry years. Historically, we’ve seen, you know five, 10 years of good water years and then a few years of dry years—it’s cyclical like that. But in this case, that cycle hasn’t broken. Something is changing.”

The drought has forced water managers to strike a delicate balance between diverting water to irrigators for crops and pastureland, and keeping enough water in the river to preserve what’s left of the riparian and wetland ecosystems that line the Deschutes.

There are currently four aquatic species in the Deschutes basin that are being threatened by the drought, habitat degradation and the river’s managed flows—and there are hundreds of farms that depend on water diversions for their livelihood.

The question is whether there will be enough water over the next 30 years in the basin to support both.

Demise of Oregon spotted frog

The Oregon spotted frog, named for the black spots that dot the frog’s back, was once prolific in wetlands and riparian habitats from British Columbia down to parts of California.

But the species has seen 90% of its habitat destroyed, most of that in the last 50 years, according to Meg Townsend, senior attorney at the Arizona-based Center for Biological Diversity.

“I live in Portland, and I’m well aware that a century ago you could have seen the Oregon spotted frog everywhere around here, including in the Willamette Valley—where it’s now completely gone,” says Townsend.

Tough going: Oregon spotted frog. Photo: USGS

The species was the first ever to be emergency listed as endangered in Canada in 1999.

In the United States, the frog was identified as a candidate for listing in 1991, but it wasn’t until litigation brought on by the Center for Biological Diversity that the species was listed as threatened in 2014.

“The Upper Deschutes is really considered one of the frogs’ last strongholds,” says Townsend.

The Oregon spotted frog is an aquatic frog, meaning it completely relies on river and wetlands to survive. After a hundred years of human manipulation of flows in the Deschutes, the frogs are struggling.

“Certain populations of Oregon spotted frog below the Wickiup Reservoir have been identified as important to protect—not just to make sure that the frog doesn’t go extinct, but to make sure it can recover and then be taken off the endangered species list altogether,” says Townsend. “If we don’t restore the habitat for the populations of frogs that live between Wickiup Dam and Bend, the frog may not have a chance of survival at all.”

Problems with irrigating an arid basin

Central Oregon’s geology makes the soils surrounding the Upper Deschutes ideal for farming, despite the arid conditions.

In the early 20th century, the uniform and constant flow of the Deschutes River gave settlers a reliable water source to support extensive irrigation.

As in most of the West, water rights in the area were doled out to settlers first come first serve, and were later adjudicated in a lengthy legal process.

The areas around Bend and Redmond, which were settled first, received the senior water rights in what’s now the Central Oregon Irrigation District (COID)—and at the time those communities were largely rural and agrarian, says Kyle Gorman, region manager at the Oregon Water Resources Department.

Field and stream: Carrot farm in Culver, Oregon. Photo: NUID/Marissa Hossick

The North Unit Irrigation District (NUID), however, which today is economically dependent on its agricultural production, wasn’t formed until after that adjudication process, which means farmers in the area around Madras have the most junior water rights on the Deschutes, and consequently receive the least amount of water in dry years.

That mismatch of rights status is “one of the great ironies of the basin,” says Gorman.

“The folks that are trying to make a living growing food and material for sustaining all kinds of industry have the most junior priority date and the least secure water supply,” he says.

Today, the Deschutes supports some 120,000 acres of farmland, ranches and residences.

Together, COID and NUID account for more than 80% of the water diverted from the river.

Under normal water conditions, COID diverts roughly 300,000 acre-feet to irrigate 45,000 acres of land, according to a 2017 report from the nonprofit Headwater Economics. But NUID diverts just 188,000 acre-feet of water to irrigate nearly 60,000 acres.

But the geology of the area has also led to incredibly inefficient diversions. The open-air ditches and porous ground conditions lead to huge transmission losses when moving water from the river to the irrigation districts. NUID can lose up to 60% of its water in diversions in low water years like last year.

“For example, we diverted 110,000 acre-feet at Bend and we delivered 36,000 acre-feet to irrigators,” says Britton. “That’s a lot of loss. The bottom falls out with the less amount of water you can deliver. It hurts and hurts in different ways.”

Water management over the last century has dramatically transformed the river’s shape and flows. Diversions on the river peaked in the 1950s, says Gorman, when the area experienced a series of unusually wet years.

“Virtually all the water that flowed from the Upper Deschutes was diverted at Bend,” says Gorman. “At times, the flow of the river [past Bend] was close to zero.”

At that time, there was no legal standing for keeping water in the river for the river’s sake. On the contrary, says Gorman, there was incentive to remove as much water from the river as possible.

“There was what we call a gentleman’s agreement to allow not more than 30 cubic feet per second to pass over North Canal Dam,” he says.

Those changes to the river’s natural flow have triggered a cascade of other issues over the years: the wetlands become disconnected from the river during low periods, and high flows in summer have widened the channel, scouring the banks of its vegetation. Invasive animals and plants have moved in, while some of the river’s native species—including the Oregon spotted frog—are struggling to survive amid degraded habitat and new predators.

“This really is the crux of the issue—how the Upper Deschutes has been managed really is the complete opposite of how a river should flow,” says Townsend. “It’s really been turned upside down.”

Keeping water in the river

Prior to colonization, the Deschutes Basin was home to the peoples that now make up the Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs (CTWS).

In the Treaty of 1855 with the U.S. government, the Tribes ceded the land where the cities of Bend, Redmond, Madras, Tumalo, Sisters and Prineville were later built.

But the tribes still hold enforceable rights for the majority of the Deschutes Basin. The CTWS’s water rights were further settled in 1997, and include instream flows in the Deschutes River for the benefit of the riparian ecosystem and its wildlife within the CTWS reservation.

Robert Brunoe, Branch of Natural Resources general manager at the CTWS, spoke about the CTWS’s water rights in a February 2023 seminar held by the Deschutes River Conservancy.

“Creator gave us gifts in order,” Brunoe told the audience. “And the first thing he gave us—or she gave us—was water. We’re supposed to take care of that water, protect that water and make sure it’s there for future generations.”

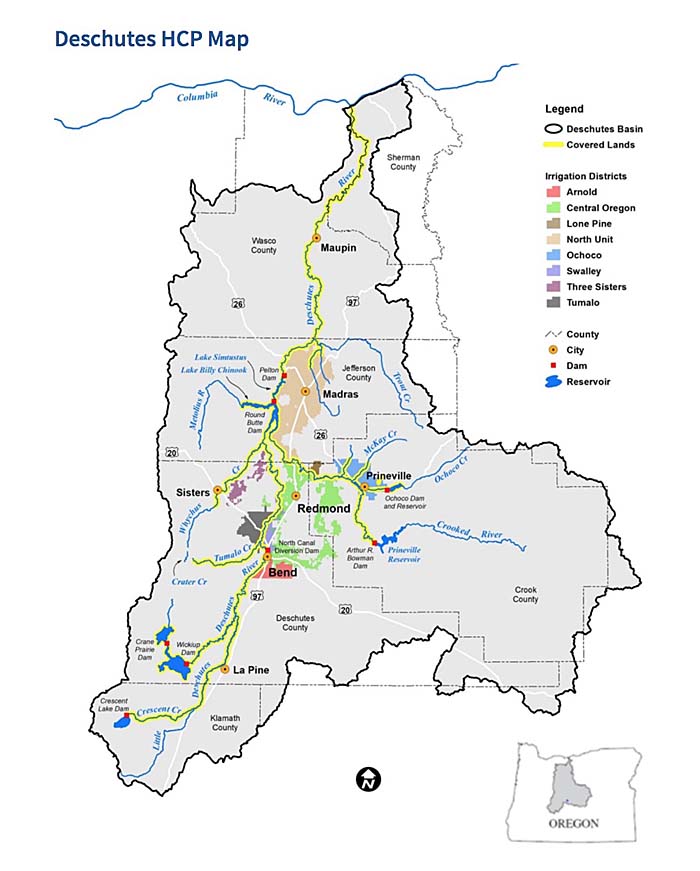

In 2008, the eight irrigation districts and the city of Prineville, along with the Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs and other stakeholders, developed a habitat conservation plan (HCP) to address the damage being done to the river’s ecology and the species that rely on it. In 2020, the plan was approved by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. It outlines a series of adjustments in water management that aim to mitigate some of the damage done to the river’s ecosystems, including increasing the winter flows, which could help the Oregon spotted frog’s chance at survival.

Deschutes Habitat Conservation Plan Map: USFWS

The plan would see North Unit increase winter flows from the current 100 cubic feet per second (cfs) to 300 cfs in the first 10 years of implementation, and aims to reach 400 to 500 cfs at the end of a 30-year period.

The HCP also outlines further water management adjustments among other irrigation districts and the city of Prineville to help the threatened fish species.

The plan is far from perfect. The CTWS expressed concerns that increased winter flows in the Upper Deschutes might negatively impact other fish species that are endangered in the river, such as the bull trout and the Middle Columbia River (MCR) steelhead.

In a 2019 filing to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the CTWS stated the HCP and related environmental impact statement “prioritize the needs of the Oregon spotted frog at the expense of other covered species, specifically the covered fish species—including Chinook salmon, the bull trout and MCR steelhead—and other tribal trust resources.”

“By failing to consider the Deschutes Basin from a holistic perspective, the [draft environmental impact statement] and HCP run afoul of the 1855 Treaty, the federal-tribal trust relationship, the ESA, the National Environmental Policy Act and applicable secretarial orders and agency policies,” the filing said.

CTWS did not respond to a request for comment on this story.

Townsend said the promised increased winter flows may not even be enough to ensure the frog’s survival. The Center for Biological Diversity released a notice of intent to sue the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service earlier this year for approving the plan, which the organization argues doesn’t go far enough to support the remaining frog populations—and, in fact, runs counter to some of Fish and Wildlife Service’s own science regarding the frog’s recovery.

Townsend points out that the 400-500 cfs winter flow target promised in the HCP falls short of the 600 cfs minimum winter flows that USFWS had determined in 2017 were required for the frog’s recovery.

So far, NUID hasn’t been able to make much progress in bringing those flows up.

“We’re three years into the HCP and they’re only getting five cfs above where we were in 2020,” says Townsend. “It’s really difficult to see how this plan will ever get to 300 cfs.”

Re-thinking water policy

All told, the HCP, the drought and the district’s most junior water rights have left NUID in a difficult position.

But Britton says the district is taking strides in water conservation efforts in order to meet the HCP requirements and also deliver more water to its irrigators.

The district is working on an infrastructure modernization project to pipe its irrigation ditches, which will reduce the district’s transmission losses.

The district is also part of a pilot water bank program, now in its second year, that would help redistribute some of the water from other districts to North Unit.

Paddle pusher: The Lower Deschutes River Back Country Byway provides access to the scenic and recreational wonders of the area. Photo: BLM

Britton says NUID is also part of an effort to tweak the state’s water law in order to accommodate water transfers between farms.

“The conservation projects we are pursuing, in-district and with outside partners, will conserve enough water [to] meet minimum flow requirements,” Britton said in an email. “We remain optimistic we’ll meet those goals.”

In the meantime, the Center for Biological Diversity is hoping to get more specific answers on how the irrigation districts will deliver on the promises made in the HCP.

“The reality is there just isn’t enough water under the current scheme to go around,” says Townsend. “Everybody needs to come together and to re-think how water is managed in Central Oregon.”