Water users in Washington and Oregon are working together to keep streams flowing in the Walla Walla River Basin

Crossing the line: Here experiencing flooding in 2020, the Walla Walla River originates in Oregon but joins the Columbia in Washington. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

By Kendra Chamberlain. October 17, 2024. Conserving water across state lines is no easy task.

Last year—for the first time ever—Washington was able to enroll an Oregon surface water right, held by the Washington City of Walla Walla, into the state’s Water Trust Program, ensuring minimum stream flows throughout the summer in Mill Creek to ensure fish migration.

An important tributary of the Walla Walla River, Mill Creek Watershed is Walla Walla’s primary source of water. It has been federally identified as having insufficient stream flow and high water temperatures, both of which severely limit access for summer steelhead and bull trout to upstream habitat.

It’s taken decades of work to get to this point, according to Brook Beeler, Washington Department of Ecology’s eastern regional director.

“In the Walla Walla watershed, the Oregon-Washington state line has long been recognized as a barrier to managing water supply and instream flows for the benefit of fish,” Beeler told Columbia Insight via email.

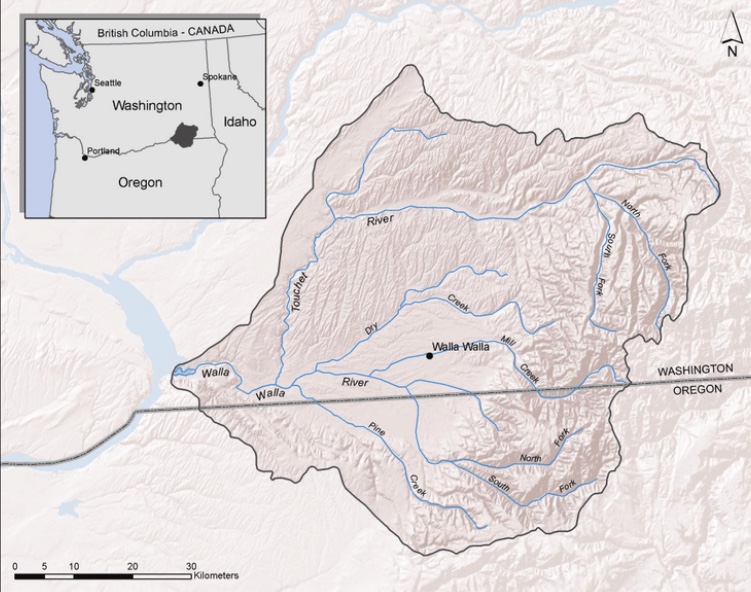

The Walla Walla River begins in the foothills of the Blue Mountains in Oregon, and flows north across the Oregon-Washington border before turning west to the Columbia River. The basin’s rivers and streams flow through both states.

Walla Walla Watershed. Map: Marc Nelitz/ESSA Technologies

European settlers developed the area into an agricultural hub of fruit orchards, alfalfa seed, onions and wine grapes—sucking up massive amounts of water in the process.

According to the Department of Ecology, water rights in the basin have been over-allocated for more than a century. Annual agricultural diversions have left streambeds dry, contributing to the extirpation of salmon.

In 2000, irrigators from Oregon and Washington settled an agreement with U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to leave water in the Walla Walla River through the dry summer months. But there was no mechanism to save that water from being legally diverted once it crossed state lines into Washington.

“After decades of water planning, a new approach was deployed by both states, the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation and local stakeholders to develop a 30-year strategy to improve streamflows and maintain sustainable water supply,” said Beeler.

The Walla Walla Water 2050 Plan was released in 2021, outlining a bi-state water management approach to coordinate efforts to protect minimum stream flows. This summer, the first out-of-state temporary surface water right was enrolled into the trust.

There were hiccups along the way, including a faulty gauge led to an over-diversion of water into Mill Creek, leaving streamflows in nearby Yellowhawk Creek unusually low.

But as the first foray into bi-state water management, the summer of 2024 marked an unprecedented achievement in the Pacific Northwest.

This is good news in a good article. But first for a brief history, the Hudson’s Bay Company had identified the Walla Walla drainage of the west slope of the Blue Mountains as a fertile well-watered valley over two hundred years ago. Salmon used the waters to build and maintain the fertility of the watersheds they spawned in, providing both the nutrients and the calories to power the distribution system. This is a good, but awfully small, step in the right direction.