A balancing act spanning two countries and a diversity of interests

Located in southern British Columbia, Keenleyside Dam (or Arrow Dam) was constructed in 1968 to meet the demands of the original Columbia River Treaty. Photo by Pat Case

By Pat Case. Feb. 21, 2019. Controversy is to be expected when managing a river that drains seven states and crosses international borders. When that same river supports a multi-billion dollar barge industry, generates over 40 percent of the hydroelectric power used in the United States and serves as the main thoroughfare for endangered runs of native fish, the inevitable currents of controversy become even more complex and harder to navigate.

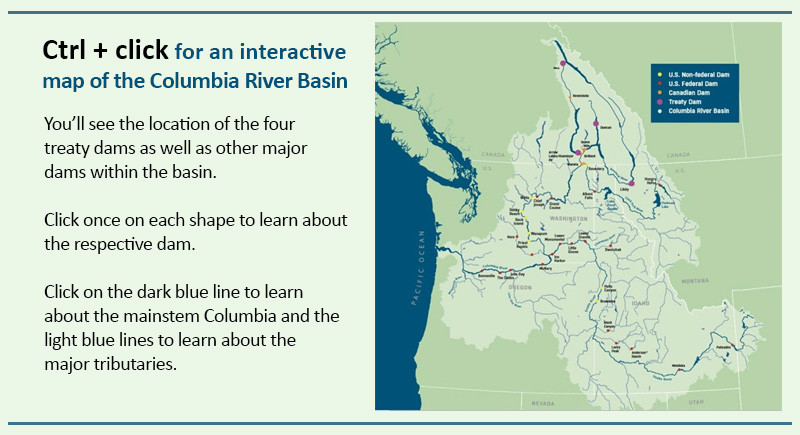

So it seems appropriate that Columbia Insight provide information on the challenges that negotiators face as they work to develop a new Columbia River Treaty. In this case, we suspect that many of our readers may not be altogether familiar with the details of what’s happening with the Columbia River Treaty and why.

And no, the Columbia River Treaty is not the treaty that governs Native American fishing rights on the river. The Treaty has a direct bearing on those rights, but it affects much more than those rights alone.

This particular treaty governs how much water flows along the Columbia River from its source in British Columbia to where it spills into the Pacific Ocean between Oregon and Washington. And during that 1,243 mile journey, this water is used in countless ways by an uncountable number of people, plants and animals.

[robo-gallery id=”10451″]

The History of the Columbia River Treaty

Implemented in 1964, the Columbia River Treaty is an international agreement between the United States and Canada. The two primary objectives in establishing the treaty were: to help prevent flooding in downriver cities such as Portland, Oregon and Vancouver, Washington; and to help ensure more reliable hydropower production at various power-generation dams along the river.

As defined by the existing Treaty, Canada — specifically the Province of British Columbia — is responsible for a network of three dams and an interconnected series of reservoirs on the Canadian side of the border. Their mandate is to manage this infrastructure in a way that benefits downriver U.S. interests in accordance with stipulations provided within the treaty.

In turn, Canada gets paid for their services through a combination of a lump sum payment and a percentage of income generated from hydropower production. In the Treaty, this payment is referred to as the “Canadian Entitlement.” Current estimates of the size of the Entitlement range from $229 million to $335 million annually.

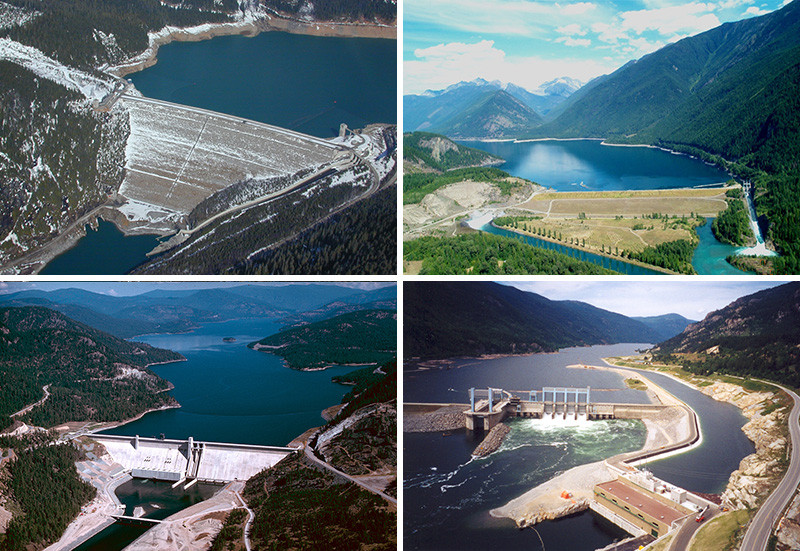

An additional dam was built on the U.S. side of the border as part of this collaborative effort. Libby Dam is located in Montana on the Kootenai River, one of the largest and uppermost tributaries of the Columbia. Collectively, all four dams — the Mica, Revelstoke and Keenleyside Dams on the Canadian side and the Libby Dam on the U.S. side — are known as the “Treaty Dams.”

Arranged sequentially (clockwise from top-left), the four Treaty Dams are located in the upper reaches of the Columbia River Basin. Photos courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

And depending on how you define the word “dam”, there are up to 500 of them in the Columbia River Basin. Looking solely at the 274 hydroelectric dams in the Basin, they range in size from the relatively small, 16-foot tall Shoshone Dam on the Snake to the monumental Grand Coulee Dam, which is located on the mainstem of the Columbia and, at a height of 550-feet, is considered one of the biggest slabs of concrete in the world.

Combined, the electricity generated by all of the major dams in the Basin accounted for 55.7 percent of the Northwest’s power grid in 2017.

And while the Treaty Dams operate independently of the other dams, they play a pivotal role in controlling the flow of water through the Columbia River. Consequently, the way in which they are managed sends ripple effects throughout the entire Basin.

The Ticking Clock

The core part of the Treaty — the part that establishes how water is stored and released from the Canadian side of the border — is set to expire in 2024 unless measures are taken to either renew or modify it.

In recognition of the ticking clock, delegates from both sides of the border are currently working to draft a new, mutually beneficial version of the Columbia River Treaty.

The U.S. State Department heads up the U.S. negotiating team, which includes four other members: the Bonneville Power Administration and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Northwestern Division (which together comprise the “U.S. Entity” that implements the Treaty in the United States), the Department of the Interior and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

The Canadian Department of Foreign Affairs, Trade, and Development has the constitutional authority to negotiate international treaties. However, the British Columbia Hydro and Power Authority (B.C. Hydro) has been the Canadian Entity engaged in the Treaty review to date.

The stated objectives for the revised treaty include the continued careful management of flood risk, the continued assurances of a reliable and economical power supply, and, notably, the addition of a third objective: to improve the ecosystem of the river and increase fish passage.

Complex Issues, Multiple Stakeholders

To date, four rounds of negotiations have taken place between the U.S. and Canadian negotiating teams.

The issues involved are complex and controversial, defying easy solutions. That’s because the treaty affects a broad group of stakeholders, including: the barges and shipping companies that use the river to transport goods; the utility companies that add renewable, affordable electricity to the nation’s power grid; commercial and subsistence fishing operations that depend on healthy fish runs; and, of course, the farmers and residents of the Basin who depend on water from the river in order to live and grow food.

Regardless of that challenge, Jill Smail, the U.S. State Department’s chief negotiator for the Treaty, said in a recent interview that the negotiating team is committed to being “faithful to the desires of people who live in the Columbia River Basin.”

Farms throughout the Basin, including this cherry orchard in the Dalles, depend on irrigation water from the Columbia in order to grow crops. Photo courtesy of Oregon Dept. of Agriculture

The desires Smail refers to were clarified over the course of several years as part of an intense effort to analyze both the technical issues involved, as well as the human and ecosystem needs.

That effort included the creation of a “Sovereign Review Team”, which is made up of regional representatives from the four northwestern states affected, 15 tribal governments and 11 federal agencies. Other inputs were gathered from the public as part of a stakeholder outreach effort, which included a series of meetings, presentations and town hall gatherings over the course of several years.

Smail has indicated that those outreach efforts will continue as negotiations unfold.

That being said, it should come as no surprise to anyone who knows anything about the history of dams along the river that opinions on the subject range from measured and mildly enthusiastic to vehement and extreme.

Some people, for instance, hold the view that the Columbia River Treaty has helped create a “mechanized” river — one that is managed in a way that exhibits little concern for ecosystem needs. They often point to the significant decrease in today’s salmon runs (when compared to historical averages), and believe that the Treaty may have done more harm to the river than good.

Others argue that the Treaty has benefitted millions of people on both sides of the border by providing irrigation, renewable energy, recreation opportunities and countless other benefits to modern society. They claim that these benefits far outweigh any harm that may have been inflicted on the river’s biological community.

A Balancing Act

The fact is that both points of view have merit. The original Treaty did not include any provisions for ecosystem benefits, but a subsequent operating provision in the Treaty (known as the Fish and Wildlife Compensation Program) enabled the creation of an additional one million acre-feet of storage at Canadian dams in order to facilitate more “fish-friendly” flows.

Still, some say the inclusion of that provision may have done little to reverse the decline of salmon and steelhead populations.

After swimming over a thousand miles through a series of major dams on the mainstem Columbia and Lower Snake, wild coho rub their fins raw building redds in Idaho’s Salmon River. Photo courtesy of BLM

That point is, of course, contentious, since dams aren’t the only factors affecting Pacific salmon populations. The fish are also threatened by agricultural runoff and the presence of invasive ungulates (also known as livestock), industrial pollution, habitat destruction by timber and mining interests, and overfishing. There are also various ocean conditions to consider such as plastic pollution, ocean acidification, commercial aquaculture and the overall warming of the Pacific due to climate change.

In any case, these sorts of operating provisions may serve as little consolation for those who hold onto the promise that the fish might someday recover to their historical numbers, thereby restoring the Columbia River’s status as one of the most productive salmon superhighways on the planet.

But it’s difficult to argue with the fact that our society benefits tremendously from the so-called “mechanization” of the Pacific Northwest’s largest river.

And so a key challenge for the U.S. negotiating team is to give due consideration to the range of varying opinions, and to reconcile them into a coherent, workable treaty that meets as many needs as possible.

Complicating the matter is the sheer size of the area we’re talking about. The Columbia River Basin is the size of Texas in terms of landmass. It encompasses the southeastern part of the Province of British Columbia, the entire state of Idaho, most of Washington and Oregon, and parts of Montana, Wyoming, Utah and Nevada.

The negotiating team’s task is made all the more difficult by their stated intention to collaborate with the Canadian negotiating team so that the two countries can reach an agreement that satisfies stakeholders on both sides of the border.

Why It’s Important

In a recent interview, Smail said that the issues at stake are vitally important because the Pacific Northwest is a “pillar of the U.S. economy.” She brought up the fact that the mainstem Columbia River dams provide more than 40 percent of all the hydroelectric power produced in the U.S., and that the river itself irrigates $8 billion worth of agricultural products and moves 42 million tons (or $20 billion worth) of commercial cargo every year.

And as Smail pointed out, the Vanport Flood of 1948 was a key impetus for the Treaty. That flood wiped out an entire community in what is now known as North Portland. More than 18,000 people lost their homes and 15 people died. The complex of dams that have been built since then gave us the power to control the flow of — and effectively tame — the mighty Columbia.

And now with the looming threat of climate change and the burgeoning populations of cities like Portland, the risk of downriver flooding may be even greater today than it was in ‘48.

The Vanport flood occured in 1948, when the Columbia River rose to 15 feet above normal levels and punched a hole in a railroad dike. Photo courtesy of National Weather Service

Smail also recognizes that the Basin provides critical and irreplaceable habitat for fish…not only for the iconic Pacific salmon species such as chinook, coho and steelhead, but for dozens of other species including lamprey and sturgeon. In addition to the economic value that these species represent to the fishing industry today, they hold a significant cultural value. Considered “first foods” by Native American cultures, they were sustaining the indigenous peoples of North America long before the ships came over from Europe.

[perfectpullquote align=”full” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]”We believe that both countries have a shared interest in a sustainable ecosystem,” Smail says.[/perfectpullquote]

That could be considered good news on the environmental front, though whether the ecosystem needs are viewed as on par with hydropower and flood prevention remains to be seen.

Key Issues

Under the terms of the existing agreement, water is managed by Treaty Dam operators in a pre-planned manner, with the goal of ensuring consistently predictable flows that meet the needs for hydropower production and flood control on a reliable basis. And in order to meet the existing requirements for flood control and hydropower production, the treaty stipulates that the U.S. and Canada must work together to prepare an “Assured Operating Plan” six years in advance of each operating year.

That’s a lot of planning, and it costs a lot of money to plan that far in advance.

So a key question going into the negotiations has been whether or not the new Treaty will require that level of planning, or if it will result in a less well-defined approach. The latter option is being referred to as a “called-upon” approach, which essentially means that water storage and release would be determined on an as-needed basis.

In turn, this question has a direct bearing on the Canadian Entitlement.

Some argue that a “pay as you go” approach could create more unpredictable flows, and consequently, would cost the U.S. more money than the current, pre-planned approach. According to this line of reasoning, unpredictable flows would result in a fair amount of crisis management, which, as a general rule, tends to inflate costs.

Motoring past Wishram, Wash., a barge heads west toward the Pacific. Photo by Cindy Mc

Another key issue has been to what extent tribal needs and concerns have been taken into consideration.

In this regard, Smail says that a decision had been made, in the interest of time, to limit the negotiating team to a small group of federal agencies. She emphasized, however, that the expertise and input of tribal members is highly valued, and that there are mechanisms in place to ensure those inputs are gathered.

What People Are Saying

A series of Town Hall meetings have been conducted by the U.S. State Department for the purpose of gathering input, and more are planned for the future.

Comments from the Portland Town Hall meeting that took place in October of 2018 were, not surprisingly, varied. People stood up to represent the interests of flood control, hydropower, tribal needs and the ecosystem.

Here are a few highlights from that meeting:

- Miles Johnson from Columbia Riverkeeper indicated that the renegotiation of the treaty offered a potential opportunity. “This is an opportunity to put the ecosystem and salmon on an equal footing with the needs of hydropower and flood control,” he said, imploring the panel to “please run the modeling to show what the temperature effects will be in the mid and lower Columbia.”

- Ted Wheeler, mayor of the City of Portland, indicated that the predictable management of floodwater is essential. He stressed that the treaty needs to be adaptable to changing conditions, and that the expertise of the 15 tribes along the river should be given full consideration. He also stressed that the treaty needs to consider the interests of shipping needs along the river.

- A spokesperson for the Sierra Club was more reticent in his comments. He questioned whether or not the river had any real voice at the negotiating table.

- Bill Bradbury, representing the Oregon Secretary of State, spoke about the importance of commerce, and indicated that both regional and national assets were at risk. He emphasized that the lower Columbia River hosts the largest wheat exporting terminals in the nation. He also emphasized that the City of Portland was at considerable risk should there be a breach in any part of the 27 miles of levees that keep the Columbia River from flowing into the city.

- Peter Marbach, a landscape photographer from Hood River, Oregon who is producing a book on the Columbia River, spoke about the Grand Coulee Dam. He asked the question of why — given the fact that it is the biggest barrier to migrating salmon — the Treaty does not seem to address this issue.

Learn More

Negotiations will continue for the foreseeable future and town hall meetings soliciting input are expected to continue. These meetings are open to the public, so feel free to attend any of them as they become scheduled — both for the purpose of learning more and to voice your opinions.

To receive regular updates regarding the Columbia River Treaty and upcoming town hall meetings, email: ColumbiaRiverTreaty@state.gov

Read the Congressional Research Service’s Columbia River Treaty Report for more information.

Monumental Reporting from Pat Case

Hands Down that global and national agencies charged with any type of resource stewardship impacting our environment could learn from these challenges and processes.

I’m hoping also that this comprehensive reporting is able to reach others who may not know about your publication.

Uh, that barge is headed West towards the Pacific, I should hope. The article certainly gives food for thought.

Thanks for pointing that out, Pj. And for reading. The caption has been updated accordingly.

Thank you Pat. I learned a lot from your article.

Great article!! Taking a complex issue, breaking it down and reporting both sides of the issues in a logical and sincere effort to inform readers. Keep it up!

The Columbia River supports the south – EAST of BC, not the west.

Thanks for the clarification, No Indians Allowed.

Salmon was never a consideration, really.

>COPY PASTE FROM Chewelah radio news< In September 2024, the Columbia River Treaty faces potential changes in flood risk management provisions between the U.S. and Canada. If an agreement is not reached, the U.S. may shift to "called upon," where Canada is asked to specify flood risk management needs. Alternatively, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers is now considering "real-time operations" or "real-time flood risk management." This shift may lead to deeper drafts in Lake Roosevelt and reduced flexibility, possibly causing a significant drawdown. Without a treaty, the dedicated Canadian flood risk management provision will expire, impacting downstream flood control needs.

Public webinars highlighted potential implications, including temporary closures of boat ramps, disruptions to ferry services, shoreline erosion, and environmental concerns such as sediment transport and changes to the thermal structure of the reservoir. Despite drawbacks, higher flows from drawdowns might benefit white sturgeon recovery efforts.

Ongoing negotiations since May 2018 involve various U.S. entities, tribal advisors, and Canadian counterparts. As the critical date approaches, the outcome of negotiations and the practical effects of transitioning to real-time operations on flood risk management remain uncertain.