Lack of hi-res data is at the core of a challenge to a logging project conservationists say could cause unnecessary damage

Stop it: Plans to build fire break in the Mount Hood National Forest, like this one under construction near Sweet Home, Ore. in 2023, are running into resistance. Photo: Oregon Dept. of Forestry

This is the second installment in an ongoing investigation into ways the U.S. Forest Service is applying powers granted to it for fire prevention to boost sales of timber to logging companies. —Editor

By Nathan Gilles. February 13, 2025. Pretty much everyone agrees that preventing wildfires or minimizing their impact is a good thing.

Most people also agree that old-growth trees are critical to environmental health and that preserving them is wise.

But what happens when these two honorable ambitions come into conflict?

This question is at the core of an argument rising to a boil over the Forest Service’s plan to cut a fuel break through a section of forest in Oregon, and the project’s use of a legal exemption that allows the agency to avoid stringent environmental oversight.

The legal exemption is tied to both the wildfire crisis and agency efforts to increase timber sales.

Located in Wasco County near the Badger Creek Wilderness, the federal agency’s 27 Road Fuel Break Project seeks to log 2,807 acres of trees to create fuel breaks around a series of National Forest System roads that snake through the Mount Hood National Forest.

Accessible as a day trip from numerous population centers, Badger Creek Wilderness is a popular recreation area. Google Maps

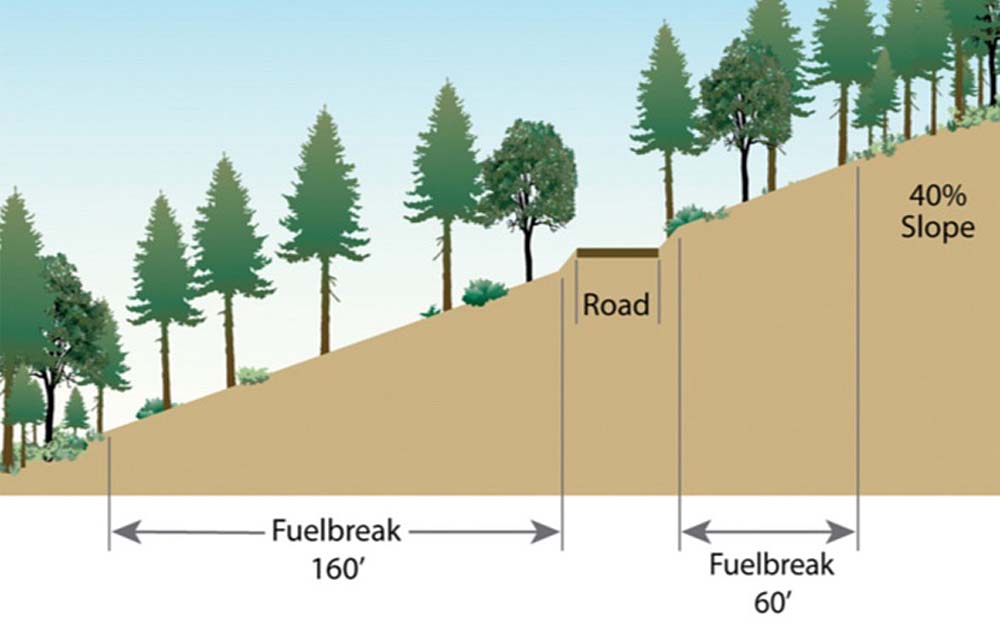

Fuel breaks are narrow strips of land where trees and other vegetation are removed or thinned to limit the spread of fire. The project proposes the creation of fuel breaks no more than 1,000 feet from the road.

Local conservationists oppose the project.

Citing a lack of technical rigor by the Forest Service, conservationists claim agency staff misapplied the region’s old-growth forest definitions, which allowed the agency to avoid the use of high-resolution datasets when designing the fuel break project.

Because of this, conservationists claim, the agency might end up allowing the logging of old-growth trees in the project area.

The fuel break project applies a legal exemption called a “categorical exclusion.”

By law, fuel breaks can be categorically excluded, or made exempt, from the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) requirement to prepare environmental impact statements and environmental assessments.

Wildfires and timber targets

Categorical exclusions are one a series of tools related to the wildfire crisis that the Forest Service has been using to meet its annual timber targets.

Internal Forest Service documents for the agency’s Pacific Northwest region office, known as Region 6, also mention fuel breaks in connection to timber targets.

The documents were obtained by the New Mexico-based nonprofit WildEarth Guardians through a public records request and shared with Columbia Insight.

Fuel break above and below a road. Graphic: Stephen Fitzgerald/Oregon State University

Internal documents include the “Fiscal Year 2024 Program Direction” for Region 6 published in October 2023, which notes that the region plans to use funding from the 2021 Bipartisan Infrastructure Law and 2022 Inflation Reduction Act intended for fuel reduction to help meet its timber sales for fiscal years 2024 and 2025.

The document reads: “Preliminary regional target assignments are 611 million board feet (MMBF) in FY 2024 and 646 MMBF in FY 2025. These volumes include additional outputs anticipated through the BIL and IRA funding for increased wildfire risk reduction, commercial thinning, and shaded fuel break work…”

Nearly the exact language was used in an August 25, 2022, email sent by the then head of Region 6, Regional Forester Glenn Casamassa, to the region’s national forest supervisors.

In the email, Casamassa calls on his Region 6 employees to “attain a minimum of 630MMBF through the ‘3+1’ strategy and up 700MMBF timber volume sold by FY26, which includes additional outputs anticipated through Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL) and recently passed inflation reduction act (IRA) funding for increased wildfire risk reduction, commercial thinning, and shaded fuel break work.”

The term “3+1” refers to a “strategy for commercial timber production” designed to create a sufficient “NEPA shelf stock,” according to Casamassa’s email.

“NEPA shelf stock,” refers to the amount of logging projects far enough along in the National Environmental Policy Act process to most likely be approved and result in timber sales.

Nature never rests: In the distance, smoke plumes from a wildfire in the Badger Creek Wilderness in 2020. Photo: Jurgen Hess

In addition to providing funding for wildfire prevention, the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law also provided the Forest Service with emergency authorities to fast-track prevention treatments by using categorical exclusions.

In February 2023, Secretary of Agriculture Tom Vilsack (who oversees the Forest Service) invoked the law’s emergency authority to reduce fuel loads within 250 high-risk firesheds nationwide.

Firesheds are the wildfire equivalent of a watershed. Most average around 250,000 acres, or roughly 390 square miles.

A February 2023 email sent to regional foresters written by David Lytle, then director of forest management, range management and vegetation ecology for the National Forest System in Washington, D.C., appears to reference Vilsack’s emergency invocation and recommends the agency “identify a variety of approaches, including tools and authorities to be identified under the Secretary’s emergency declaration” to help meet annual timber targets.

The 27 Road Fuel Break Project received its categorical exclusion authority under the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law and is listed as one of Vilsack’s 250 high-risk firesheds, according to publicly available project documents.

Science questioned

As a result of using the categorical exclusion mechanism, an in-depth environmental analysis wasn’t created for the 27 Road project.

The Bipartisan Infrastructure Law’s relationship to old-growth trees is ambiguous. The law calls for the preservation of old-growth trees while also allowing their logging if that logging is part of an authorized “science-based ecological restoration project.”

Just how science-based the 27 Road project’s design might be is the topic of a pair of letters sent by 39 conservation organizations to Jacqueline Buchanan, the current regional forester for Region 6. The first letter to Buchanan was sent in September 2024, followed by another in October.

In the September letter, the conservationists outlined multiple concerns about the project, including their claim that the project’s narrow treatment plots will result in the carving up of “contiguous areas that may have old-growth conditions, which could result in old-growth stands of substantial size being fragmented.”

Fuzzy data

Arguably the September letter’s most noteworthy claim pertains to the 27 Road project’s technical rigor. This claim has to do with a regional old-growth standard called OGSI-200, a standard that conservationists say the agency misapplied.

The Old Growth Structural Index, or OGSI-200, is a set of definitions used to identify old-growth trees. Part of the Northwest Forest Plan, the “200” in “OGSI-200” refers to 200 years, the approximate age at which many tree species under the plan can be legally defined as old-growth.

“OGSI-200” can also refer to forest survey maps and datasets that are connected to another set of Forest Service maps and datasets known as the Forest Inventory and Analysis (FIA).

Raised right: Douglas fir and Western Hemlock old-growth in Cedar Flats, Gifford Pinchot National Forest, FS Road 25, Skamania County. Photo: Jurgen Hess

Both OGSI-200 and FIA data provide something like a mile-high or overall forest-level view of the kinds of trees and their ages that can be found in specific areas.

However, neither OGSI-200 nor FIA data are especially detailed. This means that while the overall picture of the forest they provide might be correct, the fine details—actual living trees—are often missing.

Due to its low resolution, OGSI-200 should be used cautiously, says Ryan Talbott, Pacific Northwest conservation advocate at WildEarth Guardians and the lead author of both fall 2024 letters opposing the project.

“[OGSI-200] is a broad landscape, scale model that isn’t good at fine-scale analysis, like a timber sale,” says Talbott. “It’s meant to be used at [the] scale of hundreds of thousands of acres.”

Talbott and colleagues’ letters claim the Forest Service used OGSI-200 as a broad first pass that allowed the agency to eliminate multiple logging plots from old-growth protection without checking to see if old-growth trees existed in those plots.

In essence, the claim is that the OGSI-200 map is not the forest territory.

The OGSI-200 maps didn’t show old-growth conditions on 89 of the 91 plots. But whether old-growth trees are there, Talbott and others claim, is another story because finding those old-growth trees would have required higher resolution maps and data that the agency didn’t use.

As for the remaining two plots that did show old-growth conditions, the Forest Service did use finer scale data to look for old-growth trees. However, the conservationists’ letters claim the agency, rather than sticking with the OGSI-200 definitions tied to the Northwest Forest Plan, instead used pre-Northwest Forest Plan 1993 interim forest definitions.

This included using definitions that don’t apply to Wasco County and the forest types where the project is taking place, according to the letters.

Different kinds of data

What the Forest Service should have done for the 27 Road project, according to Talbott, was start with low-resolution OGSI-200, using the standard to get a general picture of the kinds of trees within the project area, then use high-resolution data to fact-check the low resolution data, a process that would have filled in the details and allowed the agency to find individual trees that might need protecting.

As it happens, this is exactly what a different Forest Service wildfire-related logging project has done.

Located in Skamania and Klickitat counties, the Little White Salmon Forest Resiliency and Fire Risk Mitigation Project is a fuel reduction and climate resilience project proposed for the Gifford Pinchot National Forest in Washington.

Slimming down: USFS foresters discuss a forest thinning operation in Washington’s Gifford Pinchot National Forest. Photo: Jurgen Hess

The project is not using categorical exclusions and has a detailed draft Environmental Assessment that is publicly available.

An appendix attached to the Little White Salmon project’s draft Environmental Assessment appears to share Talbott’s concerns about using OGSI-200 with caution.

The appendix cites previous Forest Service research, noting that OGSI-200 should be used only “to identify minimum thresholds for old growth status …”

The document describes how the Little White Salmon project was designed, including how it started with OGSI-200, then added fine details to its effort to find old-growth trees in the proposed logging plots by using high-resolution remote-sensing data, including Light Detection and Ranging data known as LiDAR.

LiDAR uses lasers mounted on satellites and aerial vehicles to map the Earth’s surface.

The appendix to the Little White Salmon project was written by Jessica Hudec, a Forest Service fire ecologist for the Gifford Pinchot National Forest, who oversaw the creation of the project and its use of high-resolution data.

In an interview with Columbia Insight, Hudec said using this additional high-resolution data allowed her team to find “substantially more old-growth” in some areas of the project “than we had identified originally in the project [using OGSI-200] …”

USFS responds

In a letter dated December 23, 2024, Regional Forester Buchanan responded to Talbott and colleagues’ letters sent in the fall of 2024.

While not ceding any ground to the conservationists regarding the 27 Road project, the letter acknowledges that different national forests in the region “have access to different kinds of vegetation data with varying levels of specificity when conducting project planning.”

Buchanan’s letter also seems to concede the conservationists’ claim that using higher-resolution data does help find old-growth trees. She writes, “We encourage units to consider use of finer scale information such as remote sensing data, stand exam data, or field observations where available to identify old growth forest conditions as this finer scale information may provide greater precision in determining the location of old growth stands on the landscape.”

Asked to comment on Buchanan’s letter, Talbott told Columbia Insight: “That sounds like the regional office doesn’t want to do what it can to protect old growth in the Pacific Northwest.”

In a February 3, 2025, letter responding to Buchanan’s letter, Talbott and colleagues again claimed the methods used by the Mount Hood National Forest are “almost certainly underestimating the amount of old-growth that is present on the ground.”

The Forest Service’s Pacific Northwest region office declined multiple Columbia Insight requests for an interview related to the project with Regional Forester Buchanan. It also declined Columbia Insight’s request for an interview, which included a list of questions, with Mount Hood National Forest Supervisor Meta Loftsgaarden.

In a January 24, 2025, email to Columbia Insight, Pacific Northwest region public affairs spokesperson Kristin Carver wrote: “After reviewing your questions more closely, we cannot offer an interview at this time. We are in a transition time, working with a new administration and we cannot speculate on future actions. … On executive orders: USDA is reviewing all the executive orders signed by President Trump and expects to share guidance on implementing them to agencies and mission areas as soon as possible.”

Fuel breaks are a good idea, logging trees to create them is a bad idea. As I age, I have the time to go through my old files and sigh about how much time I wasted on folks who didn’t learn the correct way to manage trees. I also find relatives who made REAL money making mistakes and then harvesting trees.

So, back to basics: When it rains enough to prevent fire spread across an open area, the Forest Service should take a drip torch and burn the dry fuels under the canopy. How much rain is enough to be safe?

To evaporate 1 pound of water, it takes approximately 970 British Thermal Units (BTU). Forest floor litter is about 7000 btu per pound. So, take a scale out, measure how many pounds of litter is out there, set up a rain gauge, and go figure.

Under the canopy will stay dry. When the canopy area is burned, then pick another wind free dry day, and burn the open areas.

Do that for a couple of seasons the forest floor is clear enough. Keep on doing present practices, hey, enjoy your share of zero. It is the same as many of you folks promised the Indigenous People after Boldt, ZERO.

Which of course is the income most folks have in Afghanistan.

Nathan Giles–once again–has done excellent work here, detailing the inconsistencies in Region 6 decision-making in the needed context. Direction from D.C. will doubtless push more projects into the Categorical Exclusion category–where public is given no voice. We’re seeing this already in the Oregon Coast Range Siuslaw National Forest.

Fuel breaks have no place in forests that historically don’t experience low-severity, frequent wildfire. They must be permanently maintained, where only the first entry might defray the expense. Add invasives and adjacent-stand dessication/microclimate changes from these canopy openings, and one understands that meeting an arbitrary timber target is the only justifiable explanation for these travesties.

We have GOT to get back to realistic forest management! Better to lose a few trees than the whole forest. There is nothing more terrifying than wild fire.

People really need to understand, if nothing is done to manage the fuel loadings in these forest, all the old-growth will burn up. Look at all the forests up and down the Cascade Range – large fires have burned thousands of acres of old growth. These systems are the hardest to take fire suppression efforts; there is a large fuel loading that leads to high intensity fire that gets into the crowns and spots easily. Most tradition fire suppression tools are not successful in these forest types and a change in weather is the only thing that slows them down. Plus the resource damage from trying to put out these fires far outweighs the resource damage from fire suppression efforts. And due to the high fuel loading, these are high severity fires that burn 80-100% of the trees which also means the seed source for regeneration is lost.

This project area is on the east side of the Cascades that is a drier system, has historically had the low to mixed severity, frequent fires that keep the forest more open. Using harvesting techniques to thin out these areas falls in line with the historic forest conditions and provide for fuels reduction. Harvesting is one of the quickest, most economical methods to do fuels reduction work. Doing things with hand crews takes hours of very costly work. Prescribed fire takes a large work forces (which federal agencies no longer have) and has risk associated with it. You cannot burn a forest when there is rain. Even if the understory does not get very wet, the humidity is high enough that those small, fire fuels will not burn under those conditions. I don’t like clear cut harvesting, and I’ve seen my share of poor harvesting practices and I’m a big fan of prescribed fire. But, prescribed fire alone is not the answer; there is not enough staff, money and time to do the amount of prescribed fire that needs to be done; the forest is so departed from it’s natural conditions that no amount of prescribed burning is going to get the forest back to where it needs to be in the next few years to help prevent major damage from wildfires.

Thinning is very different than clear cutting. Typically in a thinning, understory and smaller shade tolerant trees are removed, leaving the larger diameter trees that provide wildlife and other ecosystem benefits. Leaving the large trees help keep the area shaded and therefore traps more water, keeping the area from drying out as fast as say, an open clear cut area.

This project area is being focused on because the Badger Creek Wilderness is a mass of insect infected, dead trees that, under the right circumstances could cause fire to spread out into the flats where Pine Hollow, Pine Grove, Wamic, Tygh Valley, Dufur, agriculture crops, homes, ranches could be impacted. By doing road side treatments, suppression resources have a higher probability of being able to manage a fire; the road corridor already provide a fuel break, but those need to be expanded on to be effective.

I would suggest working closer with the Forest Service to understand what type of harvesting they are doing and the specifications. Work with them on the type of trees they are leaving, the equipment they are using that may have an impact on soils. Being against logging is subjecting old growth to a quick death by fire.

A few problems with the project at issue in this article. First, the Forest Service was flat out wrong in asserting there are no old-growth forest conditions anywhere in the project area. There is and they have stand exam data that shows it. But disclosing that would have slowed the process down, which wouldn’t be good for local and regional staff who are under immense pressure to boost logging to meet increasing and arbitrary timber targets set by DC (see the Columbia Insight’s first article in this series on that). And, as the article notes, they improperly used OGSI-200 to narrow it’s old-growth review to just two units and then used old-growth definitions that, by their own admission, are not applicable to this project area. There’s a serious problem when the Forest Service cites data to support its factual claim that there is no old-growth but that underlying data specifically states it doesn’t apply to the project area in question.

Second, while the Forest Service included diameter limits in a few units and inner riparian zones, most of the project area has no diameter limits. So while they are thinning from below, the lack of diameter limits for most of the project area gives the Forest Service too much discretion to take large diameter trees that are also the most fire-resistant. And, again, when the agency has been directed to meet higher timber volume targets and job performance is assessed on whether those targets are met, the lack of diameter limits puts a lot of the biggest and oldest trees on the chopping block.

Very well stated

! This fuel break is in the dry side if the forest. Not the same as the Gifford Pinchot mentioned or shown in pictures. I have visited the Road 27 fuel break & know what is proposed. Some of

The conclusions by Columbia Insight are incorrect.

Wasco County has east side forests and not the wet drippy forest of the west side of the Cascade Range and shouldn’t be treated as such. Fewer wider spaced trees is the norm for the east side forest but 100+ years of over zealous fire elimination has created very unnatural conditions. I live on the east side of the Cascade crest and consider myself to be an environmentalist and want fire to play a larger roll in how the forest is managed, and realize that fuel breaks are necessary to limit the unwanted spread of the intense fires that can occur during the late summer fire season.

I would much rather have wide fuel breaks along forest roads than to see the forest totally eliminated by wildfire like what has happened to huge expanses of the forest to the east of the Cascade crest near Mt Jefferson, where the forest trees has been replace by impenetrable scrub and the land may take centuries to revert to forest again. Tree ring data shows that centuries old trees may have experienced dozens of wildfires without being mortally harmed, but between years of fire suppression and climate change these trees are today often killed in mass when a fire breaks out.

I have said for years that if the Forest Service wanted to create a fire plan designed to create the largest possible fires it would look very similar to the fire plan that has been in place for the last 100+ years, so it is time to junk that plan and try something new and wide fuel breaks along the primary forest roads is a step in the right direction.

No disagreement about impacts of fire suppression and climate change. See my response to PJ above for general problems with the way this project was designed. Also, fuel breaks have limited utility in stopping the spread of intense fires. In large part, fires are spread by winds, which can carry embers far beyond the width of fuel breaks. The Eagle Creek fire jumped the Columbia River. If a fire can jump the Columbia River, which is essentially a mile-wide fuel break, a much smaller fuel break along Forest Service roads is not going to do anything stop the spread of fire. Federal resources would be much better spent creating and maintaining defensible space around structures and adjacent to communities.