“No man ever steps into the same river twice, for it’s not the same river and he’s not the same man.” – Heraclitus

By Dac Collins. Oct. 11, 2018. We launched on the brighter side of dawn. A lift of the bow and a firm push sent the dusty aluminum boat sliding off the trailer with a racket that offended a pair of mergansers on the far bank. The winch squealed against the weight as it slowed the slick bottom’s progress over the roller, then THWAP! The echo of the stern hitting the water bounded from one canyon wall to the next, chasing the ducks in their harried flight downstream.

(Try as we may to meet the morning’s grace with a peaceful and quiet demeanor, we humans have a way of making our presence known.)

I pulled the boat into shin-deep water before dropping the anchor and walking idly toward the gear pile. Looking down as I walked, I avoided the roundest rocks and focused on the sloshing sound my calves made in the shallow water. Its surface reflected more light with each passing second. In a few hours it would be a mirror.

Looking up, the size of the pile struck me. How long were we going to be out? Two days? I threw a dry bag over my shoulder, grabbed the cooler with both hands and, back bent, carried the load to the boat.

I recognized the sound of squeaky rubber boots on the pavement before she made her voice heard. “Where’s Willow’s food? We brought it, right?” With that, the dog trotting alongside her stopped suddenly. She looked at me, ears raised, clearly understanding the gravity of the question.

“It’s under the seat with the tarps and propane bottles,” I said, pulling the boat closer so the two of them could hop in.

“Oh!” She smiled. The dog dropped her ears, breathing easier now. Above them, the eastern skies blushed faintly. The stars had all but winked themselves out.

“The truck is locked and keys are in the spot,” she said as she dropped a leg over the side of the boat. Her other foot pushed off the bank and she turned around to take a seat as the dog jumped in behind her. “Just look at the sky! Let’s go!”

“Okay,” I said. “All systems go. If we don’t have it we won’t need it.”

In my head, I rattled through a disjointed list of “essentials”: socks, water jug, tent stakes, wine cups, chocolate, flies, first aid-kit. Then I hopped onto the rower’s seat, gave the oars a push and found myself pleasantly aware of our place in the world. Adrift.

A week before we launched at Mack’s Canyon and left the dead-end gravel road behind, I drove down to Maupin determined to learn more about the Lower Deschutes River.

Like all rivers, the Deschutes gives up her secrets infrequently and in small doses. So in order to claim with any confidence that you “know” any given river—and especially a big, brawling river like the Deschutes—you must devote a significant portion of your life to greeting it in all its lights, moods and seasons. After years of this learned devotion, patterns emerge. A language begins to develop. And although you know deep down that the only constant feature of a river is the notion that it is constantly changing, you just might start to understand why some of those changes occur.

So, seeking knowledge, I went to see two people who knew the lower Deschutes.

I met up with John Hazel and his wife Amy at their fly shop, the Deschutes Angler. Along with a grocery store, a bar, a mechanic and a couple of raft outfitters, the shop is one of the few enterprises along Maupin’s Main Street and, depending on the season and time of day, it can be one of the busiest.

“Well, when I was young it’d be 275 days a year,” John told me from behind his desk, referring to his time spent on the Lower Deschutes when he started his guiding career in the late ’70’s. “Now that I’m old it’s, you know, 60.”

In that span of forty years, the grey-bearded steelhead guide has witnessed plenty of change on the 100 miles of river below Lake Billy Chinook. As fly fishing’s popularity grew over the decades, the Lower Deschutes attained fabled status. Fish tales featuring dense clouds of salmonflies and bright summer steelhead began to circulate, and anglers started pouring in from every corner of the country. They still do.

To protect the resource, managing agencies like Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife (ODFW), Bureau of Land Management (BLM) and Oregon Parks Department began regulating the river. They outlawed bait and banned fishing from boats. They increased the production of hatchery steelhead and chinook at the Oak Springs Hatchery. They created an online permit system. They built composting toilets at some of the popular campsites and forbid the killing of wild steelhead.

Meanwhile, Hazel’s understanding of and relationship with his home water only deepened. Then, about ten years ago, when the Pelton Round Butte Hydroelectric Project reached its fiftieth year in operation, he began to notice a drastic change. More of a transformation, really.

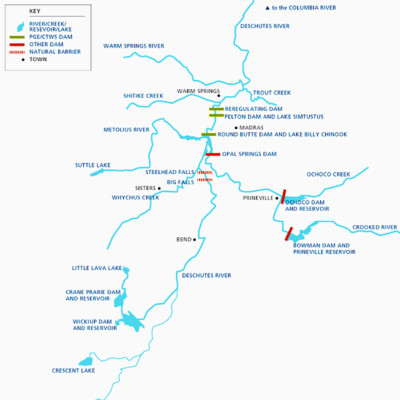

The Wild and Scenic Lower Deschutes flows north out of the Pelton Round Butte Hydroelectric Complex, which forms Lake Billy Chinook. From here, the river flows freely for 100 miles before joining the Columbia. Photo courtesy of PGE

In 2008, Portland General Electric (PGE) was required to reapply for a contract with the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) in order to continue operating its dam that, upon being built, blocked access to nearly 200 miles of sockeye, steelhead and chinook habitat. As part of that re-application process, PGE was required to mitigate these losses. So the utility came up with a plan to reintroduce these species above the dam and restore their runs to sustainable numbers. They started collecting fish from the river and transporting them above the dam with trucks. The problem remained, however, of getting the next generation of salmonids below the Pelton Round Butte Hydroelectric Complex and on their way to the Pacific.

Enter the Selective Withdrawal Tower

The idea behind the selective withdrawal tower was that if PGE could engineer a tower above the dam that would allow warmer water to spill from the top of Lake Billy Chinook instead of the bottom—as dams usually do—they could create enough current in the reservoir to pull juvenile salmonids in the right direction. Those fish could then be loaded up and trucked below the dam, where they could begin their migration to the Pacific Ocean in earnest.

So PGE’s staff of engineers and scientists collaborated with a diverse group of stakeholders— including the Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs, ODFW, the Native Fish Society and American Rivers—and formed a strategy to restore wild salmon and steelhead to the upper Deschutes Basin, and to re-establish a natural flow regime in the lower river. They touted scientific models showing that wild runs could be reintroduced to tributary streams like the Metolius and Crooked Rivers, and in 2010, they finished building the intake tower that is still in operation today.

100 miles upstream of the river’s confluence with the Columbia, a bird’s eye view of the Pelton re-regulating dam shows the selective withdrawal tower and collection facility (at bottom right), where juvenile salmon and steelhead are loaded up in trucks to be transported below the dam. Photo courtesy of Northwest Power and Conservation Council

But it was “not even close to what they initially thought,” John says, referring to how the reality of fish passage (for both adults and juveniles) through the Pelton Round Butte Complex compared to PGE’s models.

PGE spokesman Steve Corson admits that the project hasn’t been an overnight success, but he also maintains that the project is “by definition a long-term effort.”

“These runs were cut off a half-century ago,” Corson explains. “And realistically, we’re only a couple generations of fish into the process of bringing them back. We fully appreciate the fact that we’re a long way from having the kind of sustainable, harvestable runs that are our goal, and we fully expect it to take many years to get there.”

Emphasizing their commitment to “a collaborative approach to managing fisheries and water quality on the river,” Corson explains that the utility and the Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs, who co-own the hydroelectric project, are constantly seeking ways to improve fish passage at the project using adaptive management strategies. By hosting a monthly round table discussion with the Pelton Round Butte Fish Committee, PGE and the Tribes receive feedback from a variety of voices about how the project should proceed. One example of this adaptive management strategy relates to when the withdrawal tower is in operation.

“Power generation needs at the hydroelectric project have historically required passing more water through the turbines in day-time hours, but since flow through the selective water withdrawal systems is what attracts juvenile fish for downstream migration—and fish like to move at night—we found that the system wasn’t attracting fish as efficiently as we’d expected. So a couple of cycles ago we ran a pilot project to test night generation,” Corson says. “We found that it helped, so this year we began prioritizing night time flow during peak migration periods.”

Whether or not these pilot projects and other adaptive management strategies seem to be working depends on what data you look at, and on which year that data was taken. Since anadromous fish face a growing number of adverse pressures, from worsening ocean conditions and shrinking mountain snowpack to the hydroelectric gauntlet known as the Columbia River, runs can vary drastically from year to year. Likewise, the complex life cycle of salmonids makes it difficult to ascertain which of these pressures is most detrimental to the fish.

Corson points to “strong indicators that we’re headed in the right direction, such as the record-setting 463 returning adult sockeye we passed upstream in 2016 and the roughly 450,000 smolts we passed downstream in 2017.”

These promising returns were recorded long after the water quality of the Lower Deschutes began to change, however. By 2011, within a year of the tower’s installation, the effects of the lower river being fed by warmer water from Lake Billy Chinook’s surface instead of the cold, highly oxygenated water from the bottom of the reservoir were noticed almost immediately.

“All of the sudden, fishermen were scratching their heads, going, ‘What the heck happened? Where are all the caddis?’” Amy says. “You used to have a lantern full of caddis at your camp, and then there’s practically none. It was significant and it was noticeable.”

“Those were the first signs,” John adds. “The insects were completely different; the hatch timing was completely off. Then we noticed that the bird populations were changing.”

Biologists believe that these black spots are an indication of ecological changes in the lower river. Photo by Nick Wheeler, courtesy of DRA

And if those clues were disconcerting, the black spots that started appearing on the fish during the summer of 2012 were devastating. The result of parasitic flatworms burrowing into the skin of the trout, the prevalence of the disease became an unsightly reminder of how quickly things had changed.

“I was literally in a state of depression,” Amy says, “rowing past all these places where I could pull up and I knew there would be a fish there…and they [weren’t] there anymore.”

So the Hazels organized a coalition of concerned long-time Lower Deschutes anglers—some of them scientists and lawyers—to form the Deschutes River Alliance in 2013. Their goal was to create a science-based non-profit organization focused on the health and well-being of the Lower Deschutes. The DRA took PGE to court, suing the utility company for numerous violations of the Clean Water Act. They conducted their own in-depth study looking at how nutrient loads, flow regimes and water temperatures have changed since the selective withdrawal tower’s inception. They created the only thermal imaging of the entire Lower Deschutes and claimed they had proof of what they had already figured (and feared): that these negative changes in the lower river were directly correlated to the selective withdrawal tower.

“Years later, the story unfolds in court,” John says. “and Judge Michael Simon ruled for PGE. Because he’s really excited about getting wild steelhead and salmon above the [dam]. That’s his goal. And I think it’s the goal of most of the people that hold steelhead and salmon close to their heart here in the Pacific Northwest. I mean who wouldn’t support the reintroduction of sockeye, chinook and steelhead above the project? We’re all in. That’s fantastic. But the real problem here is what it has done to the water quality in the lower 100 miles. The whole ecosystem has seen a very sizable negative impact on the water quality since 2009-2010 when they started the withdrawal…So if there wasn’t any impact downstream, I guess this would be a non-issue.”

The issue remains, however, and the debate over the Lower Deschutes and its fish has only grown more contentious since Judge Simon’s recent decision. The DRA will continue to fight for the cleanest, coldest water possible in the 100 miles of river below Lake Billy Chinook, while the utility company, for its part, will continue to invest its time and energy into getting salmonids above the reservoir.

On the surface it seems like a bitter fight between two opposing forces, but the underlying irony is that both sides are in it for the fish.

Still blocked from the sun by vertical canyon walls, the three of us drifted downstream and out of sight of the boat ramp. Up in the bow, one passenger pulled down her hood before jamming her balled fists deep into her jacket pockets. The other sniffed inquisitively at the chilly September air. None of us paid any attention to the strung-up fly rod sticking out the back of the boat, but I knew it was there. For I came to the river that morning searching for steelhead, and I was full of hope.

I enjoyed your article very much, Dac. Glad to learn about the science-based coalition involved in research and collaboration since 2013. No matter how difficult and contentious the issues are, collaboration is the right approach, and it should set a standard for a wide range of nature-related, regional disputes in the decades ahead.

Thanks, Darryl. I agree with you about the value of taking a collaborative approach, especially when dealing with the management and protection of special places like the Lower Deschutes.

Bottom line; between less fish, less insects, less birds, brown slime on the rocks and PGE’s refusal to acknowledge how they have made a mess of the lower Deschutes I’ll be taking my rod and reel to other rivers. I love the Deschutes but once again, greed has ruined a pristine environment.

Until people start making a lot of noise versus running it continually through litigation this river will only get worse. I’ve made my voice heard to PGE but like most corporations it falls on deaf ears. We need collective and very public complaints, from many choices.