Retired reactors from Navy subs are also going to nuclear waste sites on top of Idaho’s Snake River Aquifer

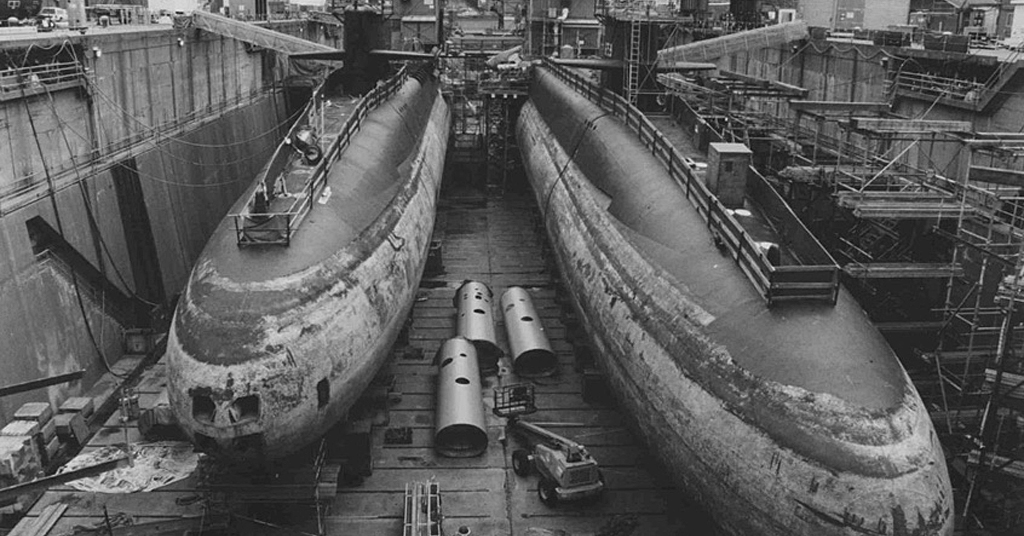

Beginning of the end: U.S. Navy submarines in dry dock for de-fueling and reactor compartment removal at Puget Sound Naval Shipyard in Bremerton, Wash. Photo: Department of Energy

A Columbia Insight article published in 2018 offered a glimpse into a relatively obscure program at the Hanford nuclear site in Washington: storage of hundreds of decommissioned reactor compartments that once powered U.S. Navy submarines. In this update to the popular story, Columbia Insight tracks the spent fuel that once powered these reactors to a facility in Idaho that, like Hanford, has a long history of environmental problems. —Editor

By Andrew Engelson. July 20, 2023. Update to article by Susan Hess originally published June 28, 2018. Compared to the massive scale of radioactive waste issues at the Department of Energy’s decommissioned Hanford nuclear site in southeastern Washington, the empty nuclear submarine reactor compartments stored there are a fairly minor part of the picture.

Hanford’s graveyard of submarine reactors nevertheless represents a messy and volatile problem.

Since 1986, the U.S. Navy has removed reactors from 123 retired submarines and eight cruiser warships and stored them in an open trench at the 581-square-mile Hanford site on the shores of the Columbia River.

At Puget Sound Naval Shipyard in Bremerton, Wash., the highly radioactive cores and spent fuel are removed from these reactor compartments, which are then carefully sealed and stored at Low-Level Burial Ground 94 (or “Trench 94”) in the 200 East Area of the Hanford Site.

Because of this sealing, and what the Navy says in a 2019 report is a 300-year durability of the casings, the compartments are treated as low-level radioactive waste by the Navy and the Department of Energy (DOE).

However, according to that same 2019 report, the empty compartments still contain substantial radiation.

Residual material found inside each former reactor contains up to 25,000 curies of radiation, enough to keep the interior dangerous for hundreds of years.

In addition, these reactor compartments contain substantial quantities of lead shielding, as well as residual PCBs in the insulation.

The Navy says it doesn’t remove the lead or PCB-laden material, because this would expose its workers to excessive radiation.

The Washington State Department of Ecology periodically monitors the reactor storage site, and an Ecology report filed in 2022 found that the trench was in compliance with state environmental regulations.

All of the Navy’s retired nuclear reactors are currently decommissioned at Puget Sound Naval Shipyard in Bremerton, Wash. In a complicated process, each submarine is placed in dry dock, and its reactors and fuel removed.

All the vessels’ equipment is stripped and the submarine is eventually cut up and recycled for scrap.

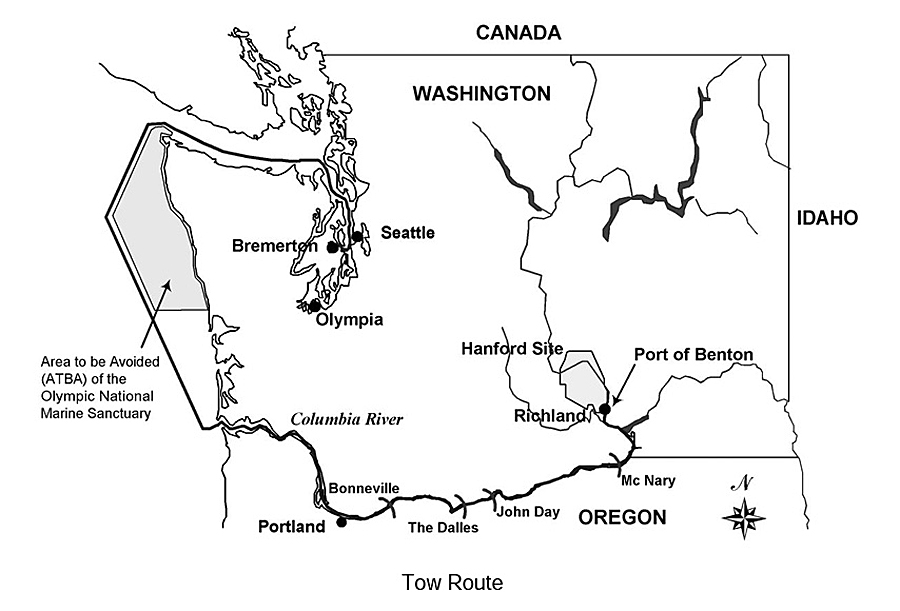

Transport route of nuclear submarine compartments. Map: Department of Energy

According to Anna Taylor, a U.S. Navy public affairs officer, the sealed reactor compartments then sail by barge out of Puget Sound, through the Strait of Juan de Fuca and south along the Pacific Coast, staying outside of the Olympic Coast National Marine Sanctuary, before eventually reaching the mouth of the Columbia River.

The reactor compartments are then barged up the Columbia River, through various locks, arriving at the Port of Benton in Richland, Wash., from where they’re trucked the remaining 26 miles to Trench 94.

“All reactor compartment packages are constructed to meet state and federal regulations for the transport and disposal of low-level radioactive waste and meet or exceed the Nuclear Regulatory Commission’s most stringent packaging requirements,” Taylor told Columbia Insight in an email.

Taylor also said the Navy currently decommissions about two submarines per year, and wrote in an email, “The task of disposing of the Navy’s nuclear power vessels will continue for many years.”

But what happens to the highly radioactive spent fuel once it’s removed from these submarines?

Where spent fuel piles up: Idaho

The U.S. Naval Nuclear Propulsion Program (NNPP) manages the life cycle of the Navy’s nuclear fuel, and oversees the removal and transportation of this high-level nuclear waste from decommissioned submarines.

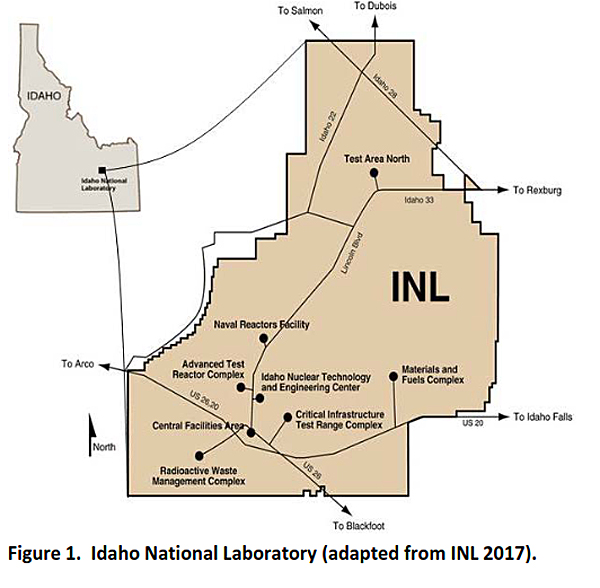

According to the Navy, after removal at Puget Sound Naval Shipyard, the spent fuel is packaged in specially designed containers that are shipped via rail by NNPP to the Naval Reactors Facility (NRF) about 50 miles west of Idaho Falls. NRF is located within the larger Idaho Nuclear Laboratory (INL), thought NRF is managed and operated separately.

Opened in the early 1950s to design and build the reactors that powered the Navy’s first nuclear submarines, the NRF has accepted all of the Navy’s spent nuclear fuel by rail since 1957.

Map: Department of Energy

According to Kevin Magic, a spokesperson for NRF, as of May 2023, the facility has received 916 shipments, accounting for about .05% of the nation’s spent nuclear fuel.

In the past three years, the Navy has made an average of eight shipments of spent fuel by rail to Idaho each year.

“To date, the NNPP has placed over 30 metric tons of naval spent nuclear fuel in dry storage, representing material from over 250 naval reactor cores,” said Magic.

Ongoing contamination of Snake River Aquifer

Both the Naval Reactors Facility and the larger Idaho National Laboratory (INL) complex have long histories of environmental contamination.

Tami Thatcher, a former engineer at Idaho National Laboratory who was a whistleblower at INL, now volunteers for the Environmental Defense Institute (EDI), a nonprofit that has long been critical of the INL. She says the INL and NRF have been contaminating the land, water and air of this 890-square-mile site for decades.

“INTEC [a facility at INL] was reprocessing research reactor fuel and submarine fuel,” Thatcher told Columbia Insight, “and from that reprocessing, there was a lot of radiological contamination to the aquifer, a lot of contamination to the air, and we still have the high-level waste resulting from that reprocessing.”

“Reprocessing” involves a series of chemical interactions that separate plutonium and fissile uranium from spent nuclear fuel. Though reprocessing can reduce the total amount of spent fuel needed to be stored long-term and increase the energy output of nuclear fuel, the United States stopped reprocessing civilian fuel in the late 1970s and all government fuel in 1992, mostly out of proliferation concerns: only a relatively small amount of plutonium is needed for a terrorist group or rogue state to manufacture a nuclear weapon. The United States limits the risk of small amounts of plutonium going missing by banning reprocessing, which puts plutonium in a much more stable state that’s easier to steal.

Open storage: Naval reactor compartment package in Trench 94 at Hanford Site. Photo: Department of Energy

Reprocessing is also a “dirty” endeavor, producing other wastes as a byproduct.

Thatcher says reprocessed waste, which was generated by the Navy between 1952 and 1992, includes calcine waste, a highly radioactive powder, and sodium-bearing waste, a radioactive liquid.

“They’ve just started [in 2022] treating that,” she said. “It was supposed to have been completed by the end of 2012.”

Leigh Ford, executive director of the Snake River Alliance, a nonprofit that considers itself Idaho’s nuclear watchdog, says that this reprocessing of wastes—including the Navy’s spent fuel—has left an ongoing, toxic legacy.

“We at the Snake River Alliance are against reprocessing because it is so dirty and dangerous,” said Ford. “It separates the uranium and the plutonium out, which is horribly dangerous and filthy.”

INL and NRF were declared a Superfund site in 1989. According to a 2016 report published by EDI, 27 tons of the Navy’s spent fuel was put into wet storage in unlined outdoor pits and trenches at various locations at INL between 1952 and 1980.

Between 1952 and 1990, INL and NRF injected nuclear waste into wells, stored waste in unlined pits and accidentally spilled wastes, resulting in radioactive materials contaminating the Snake River Aquifer, an underground water source feeding the Snake River.

Equal in size to Lake Erie, the Snake River Aquifer is North America’s second largest aquifer.

A 2019 U.S. Geological Survey report from sampling wells at INL found that radioactive materials continue to be detected in the aquifer, including concentrations of tritium and strontium-90. Cesium-137, plutonium isotopes and americium-241 were also detected, though at decreased levels from a previous study.

According to EDI, for decades INL also received shipments of Defense Department nuclear waste, commercial spent nuclear fuel, extremely toxic wastes from the Rocky Flats nuclear weapons plant in Colorado, as well as most of the radioactive material removed from the 1979 nuclear accident at Three Mile Island.

A 2020 report from the Department of Energy estimates that a total of 325 metric tons of spent nuclear fuel is stored at INF. In total, cleanup is occurring at 368 contaminated sites across INL, at a cost of $33 billion.

Accepting nuclear waste

In reaction to this massive inflow of waste, the state of Idaho signed an agreement with the Department of Energy and the Navy in 1995 and amended its agreement in 2008 and 2019.

The original agreement set limits on the amount of spent nuclear fuel the Department of Energy and Navy could ship to Idaho, and agreed that by 2035 the DOE and Navy would work to treat and remove most of the waste from the state.

However, because plans for a national nuclear waste repository at Yucca Mountain, Nev., were abandoned, it’s not clear where all of this waste will end up.

The Department of Energy says it plans to ship much of it to the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant in Carlsbad, New Mexico.

Massive haul: Retired nuclear reactor compartments are barged up the Columbia River and offloaded at Port of Benton in Richland, Washington. Photo: Department of Energy

The 2008 addendum to the agreement also required the Navy to move all the spent nuclear submarine fuel that remained in water storage at Naval Reactors Facility into dry storage by 2023. This was completed two years ahead of schedule.

The addendum also placed limits on the amount of spent fuel the Navy can ship to Idaho.

“The agreement requires that the Navy will make a running average of no more than 20 shipments per year of naval spent fuel to the INL,” said Magic, the NRF spokesperson.

In addition, the DOE was required to unbury and remove from the state at least 65,000 cubic meters of radioactive trans-uranic waste at INL. Though it recently celebrated the completion of this task, Thatcher said in an op-ed for the Idaho Falls Post Register that much low-level radioactive waste remains, including 90% of the americium-241.

“They’re leaving 100% of the rest of the waste because it wasn’t targeted for exhumation,” Thatcher told Columbia Insight. “So you’re leaving a huge burial dump and then having cupcakes celebrating.

“Cleanup is expensive. Its dangerous. And often doesn’t come anywhere near meeting published cleanup standards. They simply say: it was too hard to do that. So we’ll put a sign up and that will keep people away from it for now.”

Though the 1995 agreement now prevents most commercial waste from entering Idaho, the Navy can continue to ship its spent submarine fuel to the state until at least 2035.

And the waste keeps piling up nationwide.

A Government Accounting Office report in 2020 estimates there are 86,000 tons of radioactive spent nuclear fuel from commercial power plants stored at 75 locations across the country.

“The biggest issue is our country has no permanent repository, and so everybody’s sitting on nuclear waste,” said Ford. “The caskets are aging, and that’s a problem for everybody.”

How can I get an up dated picture? I am making a model for our submarine veterans convention.

Along with the names .

loopie@flash.net

Hi, Ciro. I took that photograph when I was on a press tour. I don’t have any more current photos. The site is in the central plateau, the most restricted area on the Hanford Nuclear Reservation so it’s not easy to get access. To get information for the article I had to contact the Naval office in Richmond. They may be able to get you a better photo. Also the site where the cores are is open so you can probably see it via Google Earth. My understanding is that the site is left uncovered because of a bilateral agreement with Russia–both countries leaving sites open.

Your article is not correct. These are not spent nuclear reactor cores from nuclear submarines. Nice for a sensational title and all, but totally inaccurate. As you state these are the reactor compartments from submarines and nuclear surface ships that have been dismantled at PSNS in Bremerton,Wa. Throughout the article, you contradict yourself many times stating reactors, spent reactor cores and such, but the reactor cores have been removed and sent to a separate site not in Hanford and are no longer contained in these compartments. These compartments and the materials they are made from will outlast us and many generations after us with no effect whatsoever to the environment. This is one of the safest ways of storing and disposing of the low level waste and other materials that are contained within the compartments. Maybe a little research and fact verification before writing and publishing will help bring true value to your article. As such as it is written now, it is nothing but inaccurate states. It sure is not news.

Fred, thank you for writing. I will check and make any necessary corrections regarding what you wrote about cores. We have corrected the article and reposted the corrected version.

Wow. Simply pointing out that there were inaccuracies probably would’ve been enough.

There are more ways to get your point across without being condescending and rude. You could have simply suggested what the issues were, without being a jerk.

Where on earth did you get your information? You are wrong yourself and maybe you’re the one who needs to do some research before bashing on someone els. You have no idea what metal those containers are made out of or what is in them either.

A better term for reactor core would be reactor fuel rods, which are removed during defueling. The control rod are not removed.

https://www.xceed-eng.com/nuclear-reactor-refueling/

No, these reactors do not use fuel rods. You’re using information from commercial reactors.

Christopher and Chad,

On a site that bills itself as “Journalism” a 200 word article with many key errors is not acceptable and reduces the credibility of the site and the author.

Had the reactor cores still remained, then that is a much different issue than just the empty reactor and reactor compartments. Those reactor compartments were made to withstand many hundreds of feet of seawater, so in a desert they should entomb their contents quite well for a long time.

Also, Hanford is about 575 square miles (depends on how you draw the borders and the time period), not 75 square miles (maybe the 200 Areas total?).

https://www.hanford.gov/page.cfm/HanfordHistory

I was employed at Puget Sound Naval Shipyard during the time that the Ship-Submarine Recycling Program was established.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ship-Submarine_Recycling_Program

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The Ship-Submarine Recycling Program (SRP) is the process that the United States Navy uses to dispose of decommissioned nuclear vessels. SRP takes place only at the Puget Sound Naval Shipyard (PSNS) in Bremerton, Washington, but the preparations can begin elsewhere.

Program overview

Defueling and decommissioning

Before SRP can begin, the vessel’s nuclear fuel must be removed, and defueling usually coincides with decommissioning. Until the fuel is removed, the vessel is referred to as “USS Name,” but afterward, the “USS” prefix is dropped and it is referred to as “ex-Name.” Reusable equipment is removed at the same time as the fuel.[citation needed]

Spent fuel storage

Spent nuclear fuel is shipped by rail to the Naval Reactor Facility in the Idaho National Laboratory (INL), located 42 miles (68 km) northwest of Idaho Falls, Idaho, where it is stored in special canisters.[1]

Hull salvage

At PSNS, the SRP proper begins. The salvage workers cut the submarine into three or four pieces: the aft section, the reactor compartment, the missile compartment if one exists, and the forward section. Missile compartments are dismantled according to the provisions of the Strategic Arms Reductions Treaty.

Until 1991, the forward and aft sections of the submarines were rejoined and placed in floating storage. Various proposals for disposal of those hulls were considered, including sinking them at sea, but none proved economically practical. Some submarines built prior to the 1978 banning of polychlorinated biphenyl products (PCBs) had the chemicals on board, which are considered hazardous materials by the Environmental Protection Agency and United States Coast Guard, requiring their removal. Since then, and to help reduce costs, the remaining submarine sections are recycled, returning reusable materials to production. In the process of submarine recycling, all hazardous and toxic wastes are identified and removed, and reusable equipment is removed and put into inventory. Scrap metals and all other materials are sold to private companies or reused. The overall process is not profitable, but does provide some cost relief.[2] Disposal of submarines by the SRP costs the Navy US$25–50 million per submarine.[citation needed]

Reactor vessel disposal

Once the de-fueled reactor compartment is removed, it is sealed at both ends and shipped by barge and multiple-wheel high-capacity trailers to the Department of Energy’s Hanford Nuclear Reservation in Washington state, where they are currently, as of 2016, kept in open dry storage[3] and slated to be eventually buried.[4][5] Russian submarine reactor compartments are stored in similar fashion at Sayda-Guba (Sayda Bay) in northwestern Russia and Chazhma Bay near Vladivostok.[6][7][8] The burial trenches have been evaluated to be secure for at least 600 years before the first pinhole penetration of some lead containment areas of the reactor compartment packages occurs, and several thousand years before leakage becomes possible.[9]

Ciro here is a link to trench 94

https://earth.google.com/web/@46.56552923,-119.51959689,170.35165048a,1010.00737328d,35y,240.79827036h,0t,0r/data=ClAaThJICiUweDU0OTg1NGE0ZGJkY2Y5ZDM6MHhhZTJhNGJkYzMxODkxMjI1Kh9IYW5mb3JkIFJlYWNoCk5hdGlvbmFsCk1vbnVtZW50GAEgAQ

hello, DDonald, This is the picture I was looking for. NOW I just need the names or hull numbers as to where they are placed. I have the 1st 130 or so. This picture is about a year old in itself.

817 991 9033 or loopie@flash.net.

Would you by chance have a contect number that I might call to get the names of all of the boats?

Let me run this WAI past the members of this group.

I’ll start by asking how much would you be willing to pay for a certificate of authenticity issued by the US DOE giving

you the exclusive right to sell or will to heirs the USS Nautilus reactor, currently resting on the Handord nuclear reservation.As you are aware adequate funding for cold war legacy cleanup is not up to the task and will take many decades to complete. There are many treasures to future generations disposed at these sites across the country.

I’m including a link to The latecomers Guide To Crypto from the Sunday New York Times business section.

Please pay special attention to the sections on NFT Nonfungable Token

and DAO Decentralized Autonomous Organization as way for the owners of the NFT’s to administer the enterprise and allocate a certain percentage of the administrative fee to cleanup. I would start the bidding at $300 for the nautilus reactor.

https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2022/03/18/technology/cryptocurrency-crypto-guide.html

Hello,

I am an old nuclear boat sailor. I am in the process of building a model of the reactor site. I am in need of the latest picture of all of the RC,s and a list of all of the names of the boats.

Any help will be greatly used.

Thank you,

Ciro

Ciro Lopiccolo

3536 Elizabeth ST.

Slidell, LA. 70458

817 991 9033

Best wishes Ciro with your project. I would love to see the final result!

The image at this site is the only one I know of that links the reactor compartments with the boats they came from:

https://wikimapia.org/1494143/Trench-94-Defueled-Nuclear-Reactor-Storage#/photo/262360

The Hanford Public Affairs Office may have a more recent photo and index.

David Winyard