Editor’s Note: Our native Quercus garryana, the Oregon white oak, is also the focus of the newly formed East Cascade Oaks Partnership. Scientists, government agencies, conservation groups, and tribes have joined together to plan how to conserve and restore remaining areas of oak woodlands and prairies. Valerie Brown wrote about this iconic oak in a Dec 2014 Envirogorge article. We thought it was time to reprint it with updated information. SEH

By Valerie Brown. June 7, 2018. Tradition has it that east and west can never meet. Turns out that’s not true. In the Columbia River Gorge east and west meet in a fascinating blend of ecological features, and there is one adaptable tree that thrives in both wet and dry Gorge habitats: The Oregon white oak, Quercus garryana.

Not only does the Oregon white oak take good care of itself wherever it gains a foothold, but it also provides a rich array of benefits for everything ranging from jays and squirrels to turkeys and truffles. The species’ modern range extends from Vancouver, British Columbia to northern California on the west side of the Cascades and from central Oregon to central Washington on the eastern slopes of the Cascades. Oaks occur along the Columbia River from the Pacific Ocean to about Goldendale, Washington, providing the only link between east and west Oregon white oak systems in the nation.

Oaks east and west

In the Pacific Northwest, Oregon white oak is far better known west of the Cascades, especially in the Willamette Valley, large swaths of which were formerly covered with oak savanna. Today these areas are much reduced but can still be seen in parts of the valley, particularly around Salem amid rolling hills, fields and vineyards. In Salem, Bush’s Pasture Park maintains an elegant stand of the oaks, which also shelter native camas along the park’s eastern border. Before Europeans arrived, the Kalapuya Indians managed the oak stands and camas using controlled burns.

But if you go looking in the Gorge for oaks like the ones in Salem, you might not find them. Q. garryana is something of a shape-shifter. Where it is grouped together with others of its kind, it grows tall and develops a canopy reminiscent of a champagne flute. Where it is sparser, growing in more open areas of scrub and grassland, it takes on a mushroom shape. And in the Gorge’s more severe habitats like cliff-faces and ridgetops, it becomes gnarled and low-growing.

The Columbia Land Trust’s oak restoration project on the lower Klickitat River in Washington is a good place to see oaks in their various shapes, says Lindsay Cornelius, the Trust’s Natural Area Manager. Along Dillacort Creek there is a short hiking trail (although with a lot of poison oak, she cautions) and plenty of places on State Road 142 to pull over and survey the landscape.

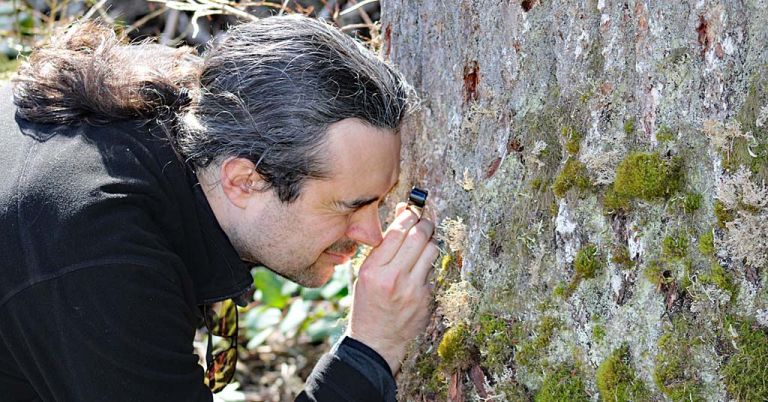

Roland Rose, U. S. Forest Service, leads a team to review a Burdoin Mountain (WA) site where it plans to remove conifers to enhance oak habitat. The oak behind Rose is obscured by surrounding conifers.

Oregon white oaks have historically been something of a poor relation to trees considered more valuable. Douglas fir is probably the richest relation, being much more desirable for timber. On the east side of the Cascades, oaks have at times been specifically removed to grow conifers for this purpose. Since fire has been suppressed, many oaks in natural mixed stands with Douglas fir have been stunted or killed because the latter grows much faster and cuts off the light. The difference in perceived value between the two species may have led people to discount the loss of the oaks.

Agriculture and development have also contributed to the oaks’ decline throughout much of their range. Overly intensive grazing, timber harvest and other ground-disturbing activities have contributed to shifting oaks’ associated plant communities to a growing prevalence of invasive annual grasses. Annual grasses provide poor nutrition to grazers; they out-compete flowering plants and native grasses; and they alter fire behavior. Along the Columbia, oaks were burned to produce steam for sternwheelers in their heyday, says Cornelius, and people still burn Oregon white oak in wood stoves. The wood is also sometimes used for flooring and furniture.

But these days the virtues of Q. garryana are starting to be better understood. While west-side groups have been working to restore oak habitat for many years, it’s a relatively new idea for Gorge and east-side conservationists.

“A number of individuals and agencies are starting to have a general conversation, a growing interest and appreciation of white oaks,” says Dan Richardson, watershed resource technician for Washington’s Underwood Conservation District. Oregon white oaks are “just about our most important wildlife tree,” Richardson adds. “Insects, birds, even large mammals like bobcats will find places to den because oaks tend to lose a limb from time to time and open up a hollow. There is a lot of cavity nesting.”

Q. garryana may also be hollow inside, says Cornelius, which means that in addition to providing all the benefits of a living tree—leaves, acorns, mycorrhizal fungi to support the roots, and insects—it also functions as a snag would function in the way Richardson describes. And speaking of fungi, the white oak is often host to numerous species including truffles, a favorite food of the threatened western gray squirrel, which prefers Oregon white oak habitat, especially in the Gorge. Some 200 vertebrate species have been associated with oak ecosystems and the list, should someone actually go looking, is likely to be much longer. Balch Lake, located in a mixed oak and pine savanna east of White Salmon, is critical habitat for one of two natural western pond turtle populations in Washington.

Mature trees that have room to spread out are particularly good for birds, including acorn woodpeckers, downy woodpeckers and scrub jays. Lichens and bryophytes on older trees host insects and other invertebrates favored by wrens, vireos and nuthatches.

East side oaks in changing climate

Oaks’ adaptability and hardiness bode well for their capacity to adjust to future disruptions, of which climate change is a major concern. Most model results, Cornelius says, is that oak range is expected to expand east, while conifer range will shrink, possibly creating better conditions for oaks. Oaks’ deep taproots allow them to find groundwater other trees may not be able to reach.

They also tolerate fire well, another advantage in a hotter climate regime.

“If an oak is burned intensely and the whole top of the tree is killed, it will sprout back from the base quite profusely,” says Andrew Bower, a geneticist with the U.S. Forest Service. Bower is studying the genetic differences between oak populations on either side of the Cascades. “A fire may kill all the leaves from this year,” he adds, “but a lot of times they’ll resprout from the trunk or branches next year.” This trait poses a challenge for groups like the Oaks Partnership.

Thirteen years ago Columbia Land Trust thinned dense stands of spindly oaks hoping that would allow the remaining trees to mature into large trees producing more acorns and nesting cavities and more resident to fire. Now they’re evaluating. “We have more questions than answers,” Cornelius says. Are those spindly trees capable of changing into the spreading canopy shape? “Then the oaks we cut down, re-sprouted, even when we sprayed and painted the cuts.”

While projects to encourage white oaks in the Gorge may not actually be returning the landscape to a pre-European configuration, there is little disagreement that fostering healthy white oak habitat is a good idea. The multiple ways Oregon white oaks provide food and habitat for many different species suggest that they can probably help stabilize ecosystems at risk from the stresses of climate change and further development.

“What I often ask,” says Cornelius, “is whether it’s important to go back to what it was, or is it [more] important [to know] what’s resilient, what’s likely to survive in the face of looming changes?”

If past evidence is any guide, Q. garryana will be able to blend the best of both worlds, east and west, wet and dry, to flourish in a future Gorge landscape.

Thanks for reprinting this article Susan – new to me. I often see the gray squirrels in association with them. And I cringe when I see people cutting down oaks with hollows. There was one on theNW corner across from the skate park that looked to be a survey marker tree. Got cut down.

Speaking of cutting, I have a concern that the city continues to cut down trees that have internal rot in Jackson Park, but they never replace them. This is in the 45 years I have observed that. We have a great city crew that maintains the parks, but I wonder if they have long term plans.

Speaking of the gray squirrels, do you have a saved up article on them and their habitat? I have the pesky red squirrels but would like to encourage the shy grays somehow. (I have one neighbor who feeds the big reds and another neighbor who calls them ‘rats with bushy tails’!)

Hi, Judy. There is a City of Hood River Tree Committee. Email me and I’ll send you information on it. I like the idea of doing a feature on the native Western gray squirrels. They get pushed out by the non-native red/brown one.

Susan

Oh, I love our oak trees. Thank you for the article.

A few years ago, I did a blog about our Camas Prairie camas and the oak trees.

http://glenwoodwashington.blogspot.com/2017/11/our-camas-flower-and-garry-oak-tree.html

This year, I saw what I think was a new field of camas blooming, north of the town of Camas, WA. And in the middle of the field was a giant old Quercus garryana.

My intention has been to gather some acorns and try to start some seedlings. Your article once again stirs my interest to give it a try.

What a beautiful, knowledgeable, and informative article, Susan. Thank you for reprinting it, since I never read it’s first publication. Greater knowledge increases my reverence and my will to contribute what I can to protect and increase the preciousness of this earthly place where we live. Is there a way to share EnviroGorge? I have some friends—one in Portland, one in Salem, and another in Eugene—who I know would love to read what you publish.

What a beautiful, knowledgeable, and informative article,

Susan. Thank you for reprinting it, since I never read its first publication. Greater knowledge increases my reverence and my will to contribute what I can to protect and increase the preciousness of this earthly place where we live. Is there a way to share EnviroGorge? I have some friends—one in Portland, one in Salem, and another in Eugene—who I know would love to read what you publish.

Thank you, Kat. For your friends in Portland and Salem, just send them the EnviroGorge link: https://columbiainsight.org/. The subscribe button is in the right hand column. Then once a week we send an email with links to our latest article. Or you can email me and I can put them on the list.

Susan

Thank you, Susan. I think they will be very interested.

I love your article, Susan. It really sets a high standard for stories about the Garry oak. Thank you for the reprint.

Thanks so much for this article. I had not fully appreciated how important the Garry oaks are to wildlife.

Those who love these beautiful trees may want to know that the city of Hood River is pushing to cut down more than 50 of them to put housing on Morrison Park, a 5-acre park in the middle of town. If this concerns you and you’d like to help save them if possible, please get in touch with Protect Our Parks, a new organization forming to protect Hood River parks: info@ProtectOurParksHoodRiver.com.

There is a lovely stand of tall oaks at Meyer Park as you drive in and first park. Are these the garyanna?

I loved the art

I enjoyed the article on Q.garryana very much. For the last 13 years we have planting various native shrubs and trees on our small farm since we stopped growing Christmas trees. We had grown Christmas trees for three decades and decided to put our efforts in a more environmental direction. Along with a variety of native plants and trees we planted a number of White Oaks. They are now about twelve years old and I am adding Garry Oaks every year. The information in this article is one of the best I have read on this subject. Douglas Tallamy’s books (The Nature of Oaks, Nature’Best Hope, etc.) have also been excellent sources of information about Oaks. It is complemented by Valerie Brown’s article that is filled with information that is more centered on our region. This is appreciated.Thanks