By Karen Schaefer. May 31, 2018. My dad howled like a fool at the full moon that night. They told me that later that night my granddad’s musty WWI army tent collapsed on me, and that I howled fit to equal my dad.

An old logging road/cattle trail threads its way some 20 miles east of Ridgeway, Colorado rising to 10,114 feet at Owl Creek Pass. My parents loved a place there at the edge of the San Juan National Forest?s wilderness. They first took me camping there the summer I turned two, the howl-at-the-moon trip.

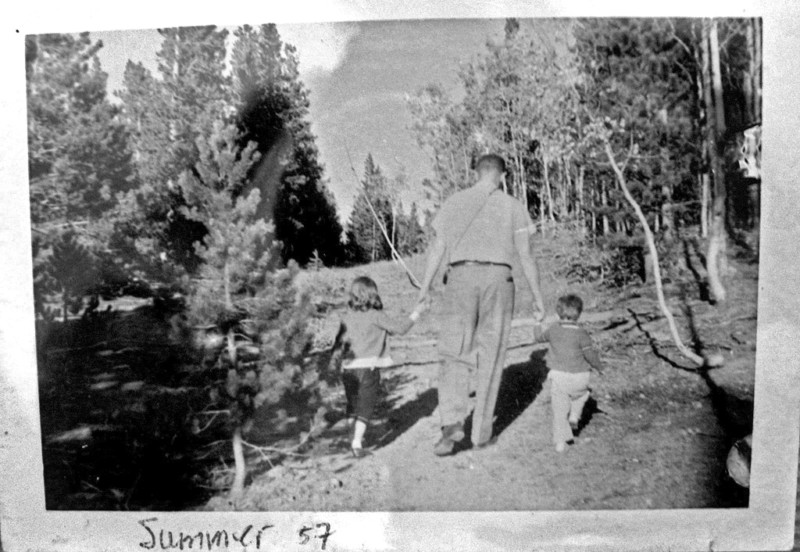

My brother was born the next spring, but my mother was ill for months afterwards, leaving me mostly in my grandmother’s care. By late summer Mother had regained her health, and my parents decided to carve out time just for me. They put my brother in the capable hands of a great-aunt for a long September weekend. And we three headed once again to Owl Creek Pass.

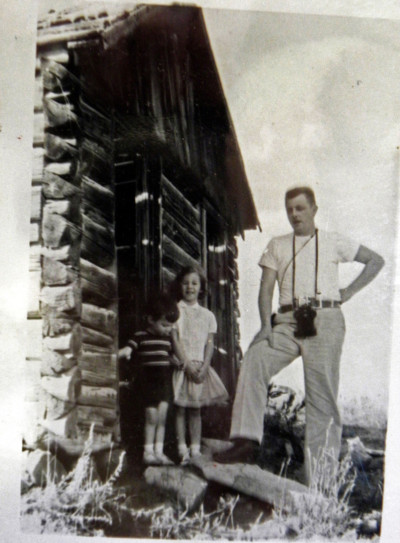

Our family went back there often in the years that followed. We drove our pre-war Buick past ranches in the valley far below. We sometimes met herds of summer-pastured cattle coming down from the high country, chaperoned by cowboys.

I loved those camping trips: singing cowboy songs around flickering campfires, loved the smell of aspen and pine that fed the flames, the twinkling star-strung Milky Way, and the yowls of coyotes. We’d hike to an overlook, where we could see the stony ramparts of Chimney Rock, Courthouse Mountain, the Sawtooth Range, and the distant smoky blue outlines of the Uncompahgre Plateau.

Another hike took us across fields of grazing cattle. “Now, watch where you’re walking,” Dad would warn my brother and me. “You don’t want to step into…Oh, Jesus Christ!”

On up the trail, we walked into a wide creek valley. A creek splashed noisily between long bars of river cobble, polished smooth by spring run-offs that re-shaped the valley every year. On one hike my dad stopped abruptly and hushed us. He hunkered his six-foot, four-inch frame down, pointing across the creek.

“Do you see there, across the rocks?” he whispered.

A big black bear and a tiny cub were snuffling up and down the creek bed for dead trout. The mama bear lifted her head and sniffed in our direction. But the wind kept her from being able to smell us. We watched the two until they ambled up into the pine forest.

We camped many places in the West, but always came back to Owl Creek. My brother and I spent whole days hanging out on the creek’s gravel bars, engineering harbors and roads through the river rocks, freezing our feet in the glacial melt. We learned to climb solo, to shimmy up a rock chimney without ropes. To climb cliffs where a slip would have meant a broken limb or worse.

We learned what plants we could eat, and which we shouldn’t touch; which streams were safe to drink from. We chilled our milk in glass bottles in the creek. Some mornings a layer of ice topped the water pail. We spent lazy hours watching golden eagles soar on the thermals above barren ridges that topped aspen and pine-covered slopes.

My brother and I learned to be on our own in the wilderness. Or so we thought.

Once, I caught my dad slipping through the forest to check on us. I realized then that he must have been doing it for years. But mostly he left us alone, to figure out for ourselves how to deal with our environment.

That freedom to explore, to believe ourselves to be alone in the mountains, was one of my greatest childhood joys. And every camping trip cemented another chink in my memory of that special place.

When I was very young, there were never any other people, except for an occasional forest ranger. Later, there were more people. But not in my childhood.

In 1973 I turned 21. That May I made one of my last trips to Owl Creek Pass. I was heading home to Durango, but passing Ridgeway I impulsively decided to drive up to Owl Creek Pass. I passed the Forest Service office wondering if I should check in, but shrugged and drove on.

The car shuddered along the familiar shelf road, as yet ungraded for the season. I looked down at the infrequent valley ranch houses. I noted with a smile the last homestead with smoke coming from its chimney. I was going into wilderness. Four miles further, I rounded a bend and braked. A massive landslide obliterated the road.

I put the car in reverse, but the tires spun in the wet clay. I was stuck. Snow began falling in thick, lacy flakes in the waning afternoon sunshine. If ever there was a moment to howl, this was one. But instead I locked the car, who knows why, and began the trek down the muddy, rutted road.

Dogs barked furiously as I neared a ranch house. A woman opened a door.

“Are you okay?”

“I’m fine!” I shouted. Cold, feet rubbed raw in places, but fine.

“We saw you heading up two hours ago,” she said. “And when you didn’t come back, my husband went up there to see what had happened to you.”

She gave me bandaids. Fed me hot coffee and soup. Gave me clean socks and boots. Her husband arrived back with my car and gently chided me.

“You were headed to Owl Creek Pass? There’s still 30 feet of snow up there.”

“I grew up in Colorado; we used to camp up on Owl Creek Pass,” I said. How had I forgotten to check road conditions, that late May is still winter high in Colorado’s mountains.

A dozen years later, I wanted to camp with my husband and our four-year old daughter at Owl Creek Pass. At the Forest Service office, we learned the road had since been cleared, but was still too rough for our car. Looping around we found another route and arrived at a small Forest Service campground just before dark, set up camp, and ate a simple meal by lamplight.

My daughter and I spent our days by the creek, wading out in the icy cold water to the gravel bar islands. Watched clouds. Chased but didn’t catch brown trout with our clumsy fingers. Built bulwarks of river cobbles to no purpose whatsoever. Watched eagles soar. Ate the wild strawberries. Gazed at the diamond-bright stars of the Milky Way until our eyes burned with tiredness. And slept in the deep wilderness quiet.

My daughter, a totally urban child, embraced it all. I learned that coming of age and loving the wilderness doesn’t have to end in your own childhood. It can go on.

Very nice! Makes me want to write one of these for the Idaho Sawtooths.

I’m like Valerie. I could picture the trail head and the Sawtooth Wilderness Area where I backpacked in many an autumn and woke up to the silence of the first snow and knew it was time to start back to the town and a job I had escaped for a time. Time when you could find pure water and the goats were not very afraid of you; when you could be alone…..

What a lovely portrait–not only of Owl Creek, but even more so of a loving family and the gifts we can pass on to our kids by lettingthem share in our memories.

Lovely, Karen, and a memory of youth that was bittersweet until the end. Such an uplifting lesson.

Do you want to go back?

Ann Hoffner, of course I do! Not sure I’ll be able to make into the high country again, though. I’m 71 now. And camping is no longer an option.