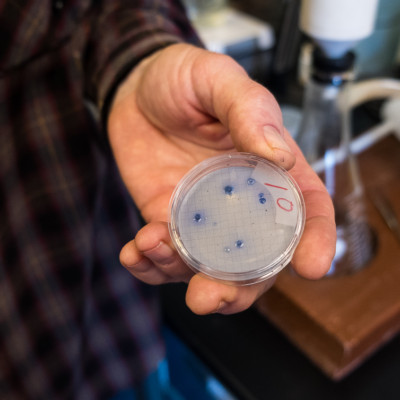

By Susan Hess. Mar. 22, 2018. Eight dark-blue, pebble-sized dots grew overnight in the petri dish Tom Hons held. Hons, who manages the Bingen-White Salmon Wastewater Treatment Plant, counted twice to make sure: 1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8. Eight fecal coliform bacteria colonies that went from invisible to visible in 24 hours.

Usually when we picture a wastewater treatment plant, should we ever think about them, it is of a circular concrete tank holding some brown substance that we don’t want to think about too deeply. But the reason they are called wastewater, rather than sewage plants, is that 99.9 percent of waste stream coming into the plant is water. Only 0.1 percent is solids. And all that water must go into the river.

Water from the kitchen sink, the dishwasher; water from the toilet and the washing machine and the shower. It all goes to the treatment plant. Wash latex paint out of your paint brush in the utility room sink and it ends up at the plant, swimming with the myriad things we put down the drain without a thought.

James ‘Buck’ Buckland and Tom Hons (left to right) work together to ensure that the wastewater leaving the Bingen-White Salmon plant meets or surpasses environmental standards. Photo by Jurgen Hess

Cue the tall and craggy Hons who, along with the mustache-sporting wastewater operator James ‘Buck’ Buckland, oversees the day-to-day operations at the Bingen plant. Both cheerful people, who love the complexities of their jobs. They follow standards set by the state—the Department of Ecology in Washington and the Department of Environmental Quality in Oregon—in order to take what comes in, called influent, and eliminate the harmful bacteria and pollutants. But today’s treatment systems are unable to eradicate newer pollutants, such as pharmaceuticals, PCBs, flame retardants and heavy metals, which are more difficult to remove.

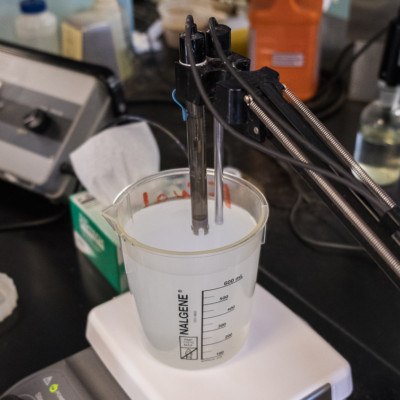

Every day, Hons and Buckland test both the influent (coming in) and effluent (going out). Samples are tested for heavy metals like cadmium, lead, mercury, zinc and copper. (Luckily there’s not much to test for because, as the soft spoken Hons says, Bingen and White Salmon have little industry.) Every space in the kitchen-size lab holds some kind of equipment to test the amount of oxygen in the water, pH levels, temperature, suspended solids and so on.

Hons’ lab is filled with specialized equipment that measures, among other things, the oxygen, temperature and pH levels of the water. Photo by Jurgen Hess

Twice a week they test for fecal coliform, an indicator species of pathogenic bacterium that can pose potential health risks. The people, along with the salmon, sturgeon and lamprey that rely on clean water in the Columbia River depend on people like Hons and Buckland to signficantly reduce the population of fecal coliform.

One way the Bingen-White Salmon plant does this is by using ultraviolet lights to disinfect the influent. The system sends water past the lights, which lowers the population of fecal coliform before it leaves the plant as effluent.

“The water that we’re sending out to the river is really clean,” Hons says. “And most bacteria are attached to particles, so if you can make the water have few particles, then you’re going to be cutting down the population.”

“Then we have limits on temperature also, like 23 to 25 degrees centigrade That’s a new limit in the last 5 to 10 years. And that’s a tough one,” he continues, “because there’s not much we can do to lower the temperature.” He and Buck talk about putting shade cloths over the aeration basin and the clarifier (settling) tanks—someday.

Temperature matters very much to salmon, as Hons explains: “Let’s say at 20 degrees centigrade, which is 68 degrees, at zero degree chlorinity, the maximum amount of soluble oxygen is essentially 9 parts per million. So think of that: 9 parts per million! That’s all the oxygen in water available to aquatic life to extract for life. To breathe!

“It doesn’t seem possible. And we have 20 percent of oxygen when we’re breathing in. So we have a pretty rich amount of oxygen available. 9 parts per million! That’s completely soluble at 20 degrees. If you get hotter than that, the solubility goes down. That’s why salmon and trout need the cold water, because of the solubility of oxygen. At 25ºC you’re down to 8.2. Those are in parts per million. So these organisms are really sensitive to how much oxygen they have available.”

According to Lori Epstein, Water Quality Director for Columbia Riverkeeper, “The ideal temperature for salmon is 5 to 13ºC.” But, she explains, “the Columbia is often above 20ºC, especially in summer. Temperatures above 25ºC are lethal for salmon, if they are in it for a length of time. Salmon leapfrog to cold refugia, like at the mouths of tributaries.” This forces them to collect in masses, where diseases easily spread, especially in hot temperatures, adding more stresses to the cascade of life-threatening conditions along the river, including dams and pollution.

The 0.1 percent that does end up at the Bingen wastewater plant is biosolid, organic matter recycled from sewage. The plant is required to reduce the solids suspended in the liquid by 85 percent.

“We’re much higher; we can be up to 99% efficiency,” Hons says. Once a year, trucks haul the biosolids to wheat and barley fields near Goldendale, where Hons and Ecology soil scientists calculate the per acre loading rate to determine the amount of nitrogen to apply.

Each blue dot in the petri dish Hons is holding represents a colony of coliform bacteria. Photo by Susan Hess

A wastewater plant is a place where most of us would work hard to not touch anything. It is, after all, full of bacteria. Most plants, like the one in Bingen/White Salmon, are activated sludge plants, which means they use bacteria—good bacteria—to consume incoming sewage as food. By balancing the temperature, pH and oxygen levels in the water, the plant operators help the good bacteria eat up that food efficiently and turn it into carbon dioxide and water.

“Bacteria are incredible at what they do,” says Hons. The day he counted the coliform in the petri dish, he talked with admiration about even these not-so-good bacteria.

“So in 24 hours, one bacteria grew into each of these colonies to be this visible. That’s an amazing growth rate! A bacteria is totally small. Totally invisible. So in 24 hours they multiplied into a visible spot that’s got billions of bacteria.”

Thanks for for the great article, Susan! Probably like most people, l have a steep learning curve on the subject. And I’ll be very careful about what goes down the drain.

Intereresting article. Not often do we hear what goes on in a waste water treatment plant. Thanks, Susan!

The old proofreader in me reared its head shouting BACTERIUM!! ?

Gosh, Thank you, Maria. We will get that fixed!

Bacteria, bacterium. I checked with a physician, a gramarian, searched internet resources. Bacteria, for those of us just learning, is the plural; and bacterium, the singular. However, even in medical journals, ‘bacteria’ is commonly used for both singular and plural. I went through the article and tried to put them right, keeping words said in quotes as the person stated them. We’re open to our reader thoughts.Chime in.

Great article! Thank you guys!

Thanks, Trish. Please let us know if you think of something we cover.

There once was a lonely bacterium,

Who wandered the sludgy mysterium.

He then joined a gang with diphtheria

And we now know him as bacteria.

Hurrah!!! So excellent, John.

Susan

Thanks so much Susan. I always wondered what went on in there!