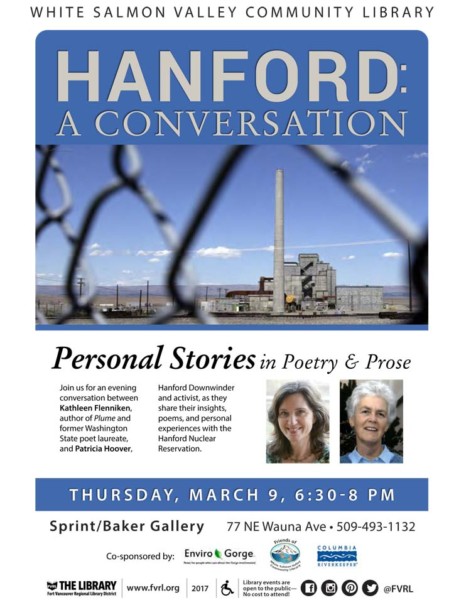

Kathleen Flenniken and Patricia Hoover will be at the White Salmon Library March 9, 6:30 p.m. A conversation about Hanford. Flenniken reads from her poetry collection, Plume, and between readings Hoover talks about being a downwinder.

Hanford Nuclear Reservation Reactors

Poet Kathleen Flenniken grew up next to the Hanford Nuclear Reservation. There may be more forbidding places than Hanford. But not many. Chemicals made on the 586 acre site are some of the most toxic on earth.

Ironically, “for a kid, it was an ideal place to grow up,” Flenniken (56) said. “It [Richland, Washington] was a city overrun with children. Almost everyone was middle class, white, of childbearing age. The schools were good.” Children at an early age picked up the culture: nobody talked about work. “It all felt normal until I moved away. Then I started to see there was a kind of tribal mentality, an us-versus-them mentality.”

Her father and all her friends’ fathers were chemists, part of the vast workforce creating plutonium for atomic bombs. That she came from this environment to become a poet, and the Poet Laureate of Washington, seems remarkable.

She grew up surrounded by brilliant scientists, people who were good parents, neighbors, and friends. They were moral, ethical, and doing their best for their country. The familiar world of science and engineering was part of her identity. She says those fields felt safe—a word not many of us would use in the same breath with Hanford. At Washington State University she graduated with a bachelor’s degree in civil engineering and returned home to work for Rockwell Hanford.

While the career fit, Eastern Washington’s desert landscape didn’t. “I never loved that landscape,” she said. “I liked the green on the west side of the state.” Adding to its allure was a boyfriend, and later her husband, in Seattle.

Once there, she plunged deeper into her career. At the University of Washington, Flenniken took a master’s degree in civil engineering, and joined a firm that specialized in the cleanup of superfund sites.

After several years, she found the work less and less satisfying. “I went into it for the wrong reasons,” Flenniken said. “I identified with the scientific people I grew up with; I liked the people, and my dad was great; he supported and encouraged me. I liked the idea of going into a formerly men-only field that in the 1980s was opening to women.”

She left the engineering field when her second child was born to be a full time mom. As anyone who has left a demanding career to stay home with small children knows, you need some outside interests. For Flenniken it was poetry. She took some night classes.

The gap between superfund sites and poetry is immeasurable, but she took poetry seriously as a vocation immediately. “This is what I was meant to do,” she said. “And I was driven to do the work I needed to do to get better.” That was part of the Hanford culture she absorbed growing up. She read poetry, took classes, joined a critique group, and her own poems were selected for publishing in small magazines at first. She started teaching and giving workshops. Washington State Arts Commission selected her for their teaching roster.

Her first collection of poems, Famous, won the 2005 Prairie Schooner Book Prize in Poetry. It was a finalist for the Washington State Book Award and named Notable Book of 2007 by the American Library Association.

In 2012 she was appointed the Poet Laureate of Washington. It’s a two year position. Two years to do what she loved. She took poetry to each of the state’s 39 counties, giving classes at the schools, especially targeting elementary schools. “I try to make poetry less scary.” She gave readings and workshops at the libraries. She developed a poetry website for the state.

Flenniken’s second collection of poems, Plume, won the Washington State Book Award and was a finalist for the Pacific Northwest Book Awards and the William Carlos Williams Award for the Poetry Society of America.

Both the poems and graphics “help tell the story, convey the feeling and history, and stay true to facts.”

She captures in poems childhood friendships, the close family life, the history of the place they referred to only as ‘the area,’ the gradual understanding of the effects those chemicals had on the people she knew and loved, what the atomic bomb did to life on earth.

“Hanford is part of my identity. It was a community built around a destructive force.”

The people, she said, were trying to be the best they could for their families, neighbors, to be good scientists doing the work no one wanted to do.

Yet, she says, “Hanford is the most contaminated waste site in our hemisphere. It’s a continuing struggle for me to make sense of my identity due to a fundamental mismatch.”

Related EnviroGorge Posts:

The Newest National Park: Hanford Reactor B

EnviroGorge Kids Writing Contest Winning Essay: Hanford

Hanford Site: A Photo Essay