[/media-credit] It cost East Fork Irrigation District $12 million to pipe 5.1 miles of their Central Canal. Standing in the 6 foot pipe from left Sharon Swyers, Mick Swyers, Cindy Sheppard.

By Sunnie Brown. Oct. 3, 2016. “It’s not all dire,” says Cindy Thieman, Watershed Coordinator for the Hood River Soil and Water Conservation District (HRSWCD). “There’s so much that we can do to save water in our basin. Even in the face of climate change, which will decrease stream flows, we can improve conditions for fish, make up for the lost water, and go beyond that.”

Each year as winter’s snowpack washes away, anxieties about water security—the valley’s reliable access to water in the future—rise. Over the years, a decreasing snowpack has become clearly visible to long-time Oregonians, regardless of profession.

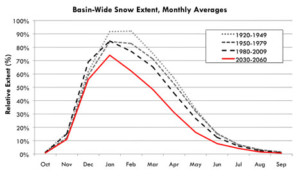

Snowpack depths on Mt. Hood have varied significantly over the past decades, but the amount of land that accumulates snow is shrinking. Since the 1920s, the Hood River basin-wide snow extent has dropped steadily; within the next 15 years, 10-15 percent of our current snow-covered areas will run off as rain instead of storing snow.

Slides courtesy of Watershed Professionals Network

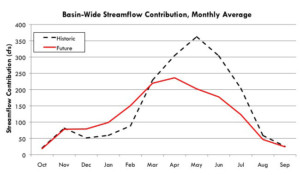

As a result of these trends, 35 percent less water will enter the streams in the spring and summer, which are the months when orchardists need substantial irrigation. Streams will carry plenty of water in the winter, but the farmers and the fish need secure flows in the warm months. With so many challenges of a changing climate, doom might seem certain. But, there is room for hope.

Irrigation in the Hood River Valley has steadily adapted to water scarcities throughout the past century. As fruit production swelled, shortages emerged, so irrigation districts diverted more streams and built reservoirs to accommodate the increasing demand. However, this time the problem is different. This time demand is steady, but supply is dropping. But this time, irrigation districts have technology and agencies on their side.

The Hood River Water Planning Group has acknowledged that historic methods, like simply increasing water input, are not feasible to conquer today’s problems. Therefore, they teamed up and received funding from the Bureau of Reclamation and Oregon Water Resources to launch investigations into the valley’s future water security.

After almost six years of research and collaboration, the project resulted in The Hood River Basin Water Conservation Strategy, a report that outlines multiple methods for conserving irrigation and potable water. The document, presently in its final editing stages, applies climate change models to forecast future flows, compares those to current water usage, and suggests potential conservation methods for farms and homes. Simply put, the study has helped identify the rate at which we need to modernize the systems. “It’s putting it all into a framework,” Ms. Thieman explains. “How much should we do in the next 20 years? How many projects should we do a year? How many acres or how many miles of ditch to pipeline should we do a year?” This type of information is useful because it helps plan and prioritize.

Improvement opportunities range from irrigation modifications and on-farm opportunities, but piping canals takes the glory. Irrigation canals were practical 100 years ago, but as we face warmer temperatures, we cannot afford to lose so much water through evaporation and seepage. However, major irrigation districts such as Middle Fork Irrigation District and Farmers Irrigation District have already piped much of their canals. This allows them to pressurize water, which returns up to 20 cubic feet (1 cubic foot=approximately one basketball) to the rivers. Imagine 20 extra basketballs floating past a given point in one second. Piped and pressurized canals better prepare us for drought, and benefit fish habitat due to the increased flows and decreased water temperatures.

According to Julie Davis O’Shea, Executive Director of Farmers Conservation Alliance in their video, “Irrigation modernization is the single greatest opportunity for supporting agriculture, creating drought resilience, and creating extraordinary conservation benefits. It’s incredible.”

Orchardists have also gained momentum in modernizing their systems. By replacing impact sprinklers (the sprinklers that shoot a large, single arch of water while clucking back and forth) with rotator ‘micro’ sprinklers, which spray a smaller area concisely and save approximately ten inches per season. Although the cost of updates daunts many growers, the benefits appear in the fruit and future costs. Micro sprinklers direct water evenly, which decreases weeds, fungus, and fertilizer leach-out, and can lead to lower labor costs.

With less storage in the form of snow, the irrigation districts are looking at increasing their reservoir space to capture increased winter rainfall. One recommendation the Hood River Basin Study proposed was adding dams and/or raising levels in existing ones to meet future water requirements. For Laurance Lake Dam that’s a 3 foot rise; Upper Green Point Reservoir: 8 feet. The study pointed to potential new storage site on West Fork Neal Creek for East Fork Irrigation.

By updating their systems, irrigators have potential to win against a changing climate—all while improving fish habitat. However, funding dictates the progression. Grant money and partnerships shape the scoreboard, project by project, but it can pay off; for example, in 2015 partners from HRWSCD and the county won a three million dollar grant for Farmers Irrigation to fix a leaky pipeline and expand storage at Kingsley Reservoir. The reservoir plans are progressing.

Unfortunately the race against climate change is tight and East Fork, the largest irrigation district in the valley, faces many barriers; the first priority is to pipe its remaining 60 miles of open canals, but it will be costly—an estimated $28 million. East Fork and groups like Hood River Soil & Water Conservation District are reaching out for funding bit by bit. “We’re hoping for a miracle,” says John Buckley, Manager of East Fork.

[/media-credit] John Buckley

Farmers and Middle Fork have put hydrogenation in their systems,which helps fund their piping projects, an asset East Fork lacks.

East Fork is still more advanced than other irrigation districts in Oregon, and was recently awarded a $600,000 grant to pipe its Highline Canal. If they continue receiving more grants, even bits at a time, 30-35 CFS will eventually be returned to the East Fork of the Hood River. Mr. Buckley estimates the district’s canals lose up to 20 percent of their water. “EFI needs to have sources available to pipe at a much faster pace than what it is currently doing,” he says. “Canals have got to be a thing of the past.”

Mr. Buckley thinks the dam for East Fork proposed in the basin study will not hold the amount of water they need. The Basin Study identified the West Fork Neal Creek as a potential reservoir site. It could provide 2,557 acre-feet of new storage. But according to Mr. Buckley, “The District would like to find a site that could hold about 5,000 acre-feet of water for irrigation purposes.” They’ve discussed other options, but funding is still lagging. “The District,” he says, “will continue to pipe open systems to help with conservation and improvements.”

Although East Fork sputters behind Middle Fork and Farmers, the successes of the leaders allow the attention and action to focus on East Fork. With reliable data, strong partnerships, and a strengthening economy, there’s optimism for future funding opportunities. Beating climate change will not be a swift or simple battle, but there’s reason to hope and surge forward.

Cited Sources:

Thieman, Cindy, Ed Salminen, Nikalas Christensen, and Jason Keller, RG. The Hood River Basin Water Conservation Strategy. Working paper. The Hood River Watershed Group. N.p.: Watershed Professional Network, LLC, n.d. Print. In Press.

Thieman, Cindy, and Nikalas Christensen. “The Hood River Basin. Opportunities for a Sustainable Future.” Hood River Watershed Group and Watershed Professional Network. N.p.: n.p., n.d. Print. PowerPoint Presentation.

Another great Envirogorge piece, highlighting the importance of irrigation efficiency upgrades to maintain regional agriculture while leaving more water instream for our endangered fish and wildlife.

Thank you, Nick.

Did Bryant pipe and supply supply the piping or design the project for East Fork? It seems they are show cased.

Mark, Thanks for bringing this to our attention. The article was assigned and written before we asked Bryant Pipe if they would like to advertise on Envirogorge. We are new to getting advertising and we didn’t consider the connection, but certainly will for the future. We are working on finding ways to pay our writters and staff to continue our mission. We hope that readers like you will support us.