By Valerie Brown, Feb. 19, 2016. The recent news that Flint, Michigan children have been poisoned by lead in their drinking water has rekindled the nation’s anxiety about this toxic heavy metal. But is the Flint scandal just a local disgrace or should the rest of us be concerned about unexpected sources of lead exposure?

Lead was formerly used in paints, gasoline, and countless consumer goods. But it was found to be a health hazard. In adults, lead exposure has been associated with high blood pressure and kidney failure, and in children with aggression, attention deficit disorders, loss of IQ points and other neurological problems. Getting lead out of gas and paint in the 1970s caused a radical drop in Americans’ lead ‘body burden,’ which in turn has been credited with, among other effects, lowering the crime rate.

[/media-credit]

[/media-credit]

Thus much lead exposure these days is of the ‘legacy’ sort–from remodeling homes built before 1978, in plumbing held together by lead solder, and in batteries and ammunition (although it has not been banned from plastic and still remains a worrisome contaminant in many products ranging from lipstick to children?s toys and imported candy).

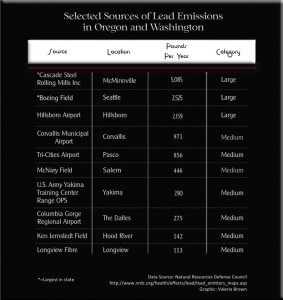

But the largest source of airborne lead that remains unregulated is avgas, also known as ‘100LL’ – the most common fuel used by piston-engine airplanes and helicopters. These are the small aircraft that use general aviation airports like Columbia Gorge Regional in The Dalles and Ken Jernstedt Field in Hood River.

Evaluating the dangers of lead from general aviation sources requires balancing a number of considerations: For example, while lead is a dense, heavy metal, it is ground so fine in avgas exhaust that much of it can travel far from the point of emission.

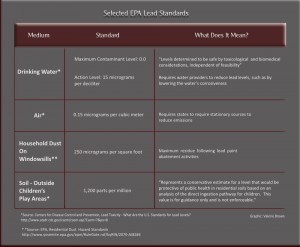

And even though blood lead levels are declining, researchers have found that the steepest increase in health effects occurs at the lowest levels of exposure; and it is very clear that there is no threshold no ‘safe’ level of exposure below which we need not worry about damage.

In the 1960s the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention set allowable blood levels at 60 micrograms per deciliter (mcg/dL), lowered them to 10 in 1991, and has recently lowered them yet again to 5 mcg/dL in response to the news that there is no threshold for harmful effects. The CDC estimates that about half a million U.S. children have blood levels above 5 mcg/dL. Damage to academic performance has been measured at levels as low as 2 mcg/dL – so children continue to be at risk even as lead in their environment decreases.

[/media-credit]

[/media-credit]

It would be impossible to remove 100% of the lead from the environment or our bodies, but regulators still have to come up with some benchmarks that end up being de facto thresholds. (See sidebar.)

While general aviation is a small part of overall aviation, it may be a significant source of local lead exposure. A 2011 study revealed that about 16 million people live within 1 kilometer of a general aviation airport, and 3 million children attend school within that perimeter. The closer the residence to the airport, the higher the blood lead levels in the children living there. And while the ambient lead level falls off rapidly with distance from the source, airport levels have been measured at more than four times the concentrations in the general environment, and are higher downwind than upwind of an airport.

Except for a few steel and lumber mills, the most significant lead sources in Washington and Oregon are airports, most emitting hundreds of pounds annually. In Oregon the second-highest source of lead emissions is the Hillsboro Airport, which releases about a ton into the skies every year – nearly twice Portland International Airport’s emissions. Hillsboro’s figures are a direct result of the extremely high number of operations at the airport attributable to general aviation flight lessons.

[/media-credit]

[/media-credit]

According to the Aircraft Owners and Pilots Association, the reason pilots don’t yet make much use of the nine potential alternatives to avgas is that without leaded fuel, a small piston engine is susceptible to forces that would “literally tear itself apart during operation.” Although the AOPA participates in a broad coalition of organizations including the FAA and the EPA working toward a substitute fuel, there is still no deadline for eliminating lead from aviation fuel.

A consortium of environmental groups including Friends of the Earth, Physicians for Social Responsibility and Oregon Aviation Watch has petitioned the EPA to take action, but the EPA remains unwilling to consider an endangerment finding for avgas, putting its decision off until at least 2018. An endangerment finding would require the EPA to take steps to protect human health.

In the meantime, says epidemiologist Bruce Lanphear, a childhood lead exposure expert at the University of British Columbia, “We are [allowing continued use of avgas] on the backs of future generations. It has to stop. The question is when. It’s a technology that is obsolete. It should be banned or phased out.”

As the global aircraft industry is expanding at a decent pace, competition among aircraft fuel production in all sectors is also getting intense.