Tribes, environmental groups and the state of Washington challenge Douglas County PUD’s bid for low impact certification for Wells Dam

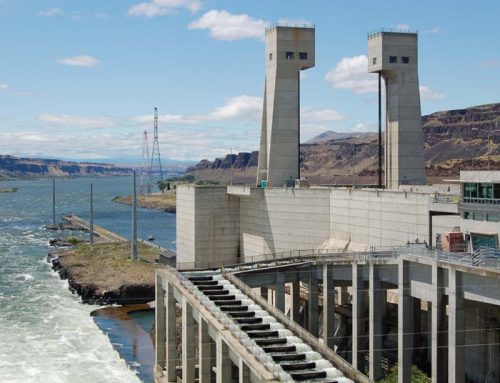

Big impact: Wells Dam is an 840-megawatt hydroelectric facility on the Columbia River spanning from Douglas County to Chelan County in Washington. Photo: Schnabel Engineering

UPDATE: On Nov. 25, 2025, the day after this story was published, Maryalice Fischer, certification program director for the Low Impact Hydropower Institute, informed commenters on the Wells Dam LIHI application that LHIH would be dropping its dam certification evaluation for the dam. “I am writing to inform you that Douglas PUD has elected to withdraw their LIHI application for the Wells Dam project located on the Columbia River in Washington,” Fischer wrote in an email sent to more than 25 government, tribal and nonprofit representatives, and other organizations. “We will not be conducting further evaluation of the project at this time.” —Editor

By Nathan Gilles, November 24, 2025. The Wells Dam Hydroelectric Project lies on the Columbia River near the Washington cities of Pateros and Bridgeport roughly 500 miles from the river’s mouth at the Pacific Ocean.

Environmental activists say the dam, which has been producing hydroelectric power since 1967, has destroyed 25 miles of Columbia River habitat, as well as habitat on the lower Okanogan River.

Although the dam has fish passages for migrating salmon and steelhead populations, critics of its operation are calling for changes they say are needed to help fish get to and from the Pacific.

Nonetheless, if the dam’s owner and operator, the Douglas County Public Utility District, gets its way, the Wells Dam could soon be one of just two hydropower facilities on the main stem of the Columbia River to be certified as “Low Impact Hydropower,” a move that could give the power provider both a reputational and economic boost.

Local environmental organizations, the state of Washington and the Confederated Tribes and Bands of the Yakama Nation oppose certifying the facility.

The would-be certifier is the Low Impact Hydropower Institute (LIHI), a Boston, Massachusetts-based nonprofit that has been certifying dams as low impact since the early 2000s.

“We are a low-impact, not a no-impact organization,” LIHI Executive Director Shannon Ames told Columbia Insight in a phone interview.

“Every single renewable resource or otherwise has an impact on the environment,” Ames said. “We’re trying to make a difference where hydro is concerned.”

Selling ethics

According to LIHI’s website, 186 hydropower facilities currently have LIHI certification, most in the eastern United States.

To date, LIHI has certified just 10 dams in Oregon and three in Washington.

As consumers we’ve become familiar with certifications for fair trade, organic and B Corp products. Communicated with distinctive logos, certifications proclaim that a product’s manufacturing or sourcing has adhered to the highest labor, environmental or other ethical standards.

Certifications ask us to vote with our dollars. In this way, we incentivize makers of goods to do good as well.

LIHI’s low impact hydropower certification is intended to work in a similar way. Think of it as a market-based carrot to federal and state agencies’ regulatory stick.

To receive LIHI’s low impact hydropower certification, a dam must “meet eight specific science-based environmental, cultural and recreational criteria” established by LIHI, according to the group’s website.

These criteria, which include providing fish passage and protecting threatened and endangered species, tend to correspond to federal and state environmental laws. That’s the stick.

The carrot in this scenario is that once certified by LIHI a dam’s power can be marketed as low impact. Here state laws help.

In efforts to lower their carbon footprints, multiple U.S. states have passed laws establishing “renewable portfolio standards” (RPS) for electricity. RPS laws tend to require large companies operating within a state’s borders to purchase a portion of their power from low carbon sources.

These laws also frequently provide marketplaces where state-mandated low carbon power can be purchased.

Douglas County PUD decision

To determine what power sources can be sold on their marketplaces—what qualifies as “low carbon” or “renewable” or “clean” energy—multiple states have turned to outside certifiers. LIHI is one of them.

At least five states require LIHI certification to sell power as part of their renewable portfolio standards, including Oregon.

Currently, eight of 10 LIHI-certified hydropower facilities in Oregon and one of the three facilities in Washington are approved to sell power on Oregon’s Renewable Energy Credit (REC) market.

Douglas County in red. Map: Wikimedia Commons

The Washington facility is the Dalles Dam on the Columbia River. A section of the dam was certified by LIHI in 2015.

Whether Douglas County PUD plans to sell Wells Dam’s power on Oregon’s REC market is unclear.

The push to certify the dam is being overseen by Douglas PUD’s Shane Brickford and Andrew Gingerich, according to documents submitted to LIHI. Neither man returned phone calls requesting comment.

Meghan Vibbert, Douglas County PUD public relations officer, declined to comment for this story.

Douglas PUD sells power to the Washington-based Puget Sound Energy, which a September 2024 press release credits with helping the company achieve its “decarbonization goals.”

In addition to LIHI certification, dams that want to sell power on Oregon’s REC market must register with another nonprofit, the Western Renewable Energy Generation Information System.

Douglas PUD has registered the Wells Dam with WREGIS, according to WREGIS’s website.

“Certain important parties” unaware

In her interview with Columbia Insight, LIHI Executive Director Ames highlighted the science-based standards her organization uses when certifying a dam.

She also stressed her organization’s transparency, including how LIHI holds a public comment period for every dam it considers certifying.

Ames, however, declined to comment on the Wells Dam application itself, saying only that the dam’s public comment period had been extended when her organization learned “that certain important parties were not aware” of Douglas County PUD’s application with LIHI.

Shannon Ames. Photo: LIHI

LIHI’s guidelines require applicants to provide contact information for “relevant state, federal, provincial and tribal resource agencies.”

The important parties not notified were the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife and the Confederated Tribes and Bands of the Yakama Nation.

The two groups co-manage the Wells Dam’s Habitat Conservation Plan with Douglas County PUD.

In its application to LIHI, Douglas County PUD failed to provide contact information for its co-managers.

The conservation plan is designed to help anadromous fish, including legally protected salmon and steelhead populations, traverse the dam on their trips to and from the Pacific Ocean.

The Wells Dam lies within the historical territory of the Yakama Nation, which has treaty-protected fishing rights that give the Tribe management authority over fish bypassing the dam.

According to letters sent to LIHI and posted to the group’s website as part of the public comment period, while Douglas County PUD first submitted its application to LIHI in May 2024, WDFW and the Yakama Nation didn’t hear about the proposal until October 2024, after LIHI had already issued a preliminary approval for the Wells Dam to receive low impact certification.

Not surprisingly, both WDFW and the Yakama Nation were unhappy with being left in the dark.

“The application for certification is lacking in its omission of the relevant fisheries co-managers from the contact list and does not adequately address the fisheries related issues identified above,” wrote Gerald Lewis, chairman of the Yakama Nation Tribal Council in an Oct. 21, 2024, letter to LIHI.

Lewis couldn’t be reached for comment.

Keely Murdoch, a fish biologist employed by the Yakama Nation who has been overseeing the Tribes’ interactions with LIHI, did not respond to email questions sent by Columbia Insight.

A Nov. 15, 2024, WDFW letter to LIHI, starts by informing the Boston nonprofit that both WDFW and the Yakama Nation have “statutory co-management authority over Columbia River salmon and steelhead.”

What is a “low impact” dam?

The letters sent by WDWF and the Yakama Nation in the fall of last year outlined concerns the groups have about the fish management at the Wells Dam and why they thought certifying it as low impact was unwarranted.

Included are a series concerns about what the groups claim is inadequate monitoring of ESA-listed spring chinook, high mortality rates for steelhead at the dam and low numbers of Pacific lamprey passing the dam.

While WDFW and the Yakama Nation’s arguments against certifying the Wells Dam get well into the management weeds, they boil down to a debate about what the term “low impact hydropower” should mean and whether the dam meets LIHI’s criteria by simply complying with the law.

What’s green? The Wells Dam in Douglas County Washington delivers power to Confederated Tribes of the Colville Indian Reservation, Puget Sound Energy, Portland General Electric Company, Avista Corporation and Okanogan County PUD. Photo: Douglas County PUD

In documents sent to LIHI arguing for low impact certification, Douglas County PUD has championed the Wells Dam conservation plan and the dam’s compliance with state and federal environmental laws.

However, in their own letters to LIHI, WDFW and the Yakama Nation dispute these claims, saying the dam’s conservation plan doesn’t do enough to protect struggling fish populations. They argue that the plan and compliance with the law by itself shouldn’t be enough to certify the dam as low impact.

This is also the position taken by the Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fish Commission (CRITFC).

Pete McHugh, fish passage scientist at CRITFC, told Columbia Insight that one reason his organization is opposing certification is that while adhering to rules of the Endangered Species Act have kept some fish population from going extinct, simply following the law shouldn’t be enough for LIHI to certify Wells Dam.

“Columbia Basin chinook salmon and steelhead, they’re not doing much better than when they were first ESA listed,” said McHugh. “So, just conceptually, it [low impact certification] really should be reserved for something special rather than projects that are meeting their obligations.”

CRITFC is a joint effort between the Yakama Nation, the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation, the Confederated Tribes of the Warms Springs Reservation of Oregon and the Nez Perce Tribe. CRITFC’s stated goal is to protect and restore salmon, sturgeon and lamprey populations in the Columbia River Basin.

“Quasi-regulatory agency”

In spring 2025, WDFW, CRITFC and the Yakama Nation decided on a new strategy in dealing with LIHI, one that would use the certification process as leverage.

How they plan to do this is laid out in a March 12, 2025, letter to LIHI signed jointly by representatives from the three groups.

The letter starts by reiterating the groups’ position that to earn LIHI’s low impact certification, a dam owner should be “advancing species recovery” beyond its “minimum legal requirements.”

The letter then lists a series of changes that Douglas County PUD should make at Wells Dam if LIHI certifies the facility.

“There’s nothing low impact about a 60-year-old hydropower facility that drowned 25 miles of the Columbia River.”

The list of requested changes addresses concerns about management of spring chinook, steelhead and Pacific lamprey populations.

Under this joint proposal LIHI would make continued certification of the dam contingent on Douglas County PUD meeting the groups’ requests.

However, as the letter states, implementing the changes will be difficult, suggesting that the true intent of the proposal is to make oversight of the dam so onerous for LIHI that the nonprofit decides to cut its losses and deny certification.

In an interview with Columbia Insight, Michael Garrity, special assistant for Columbia River Policy at WDFW, hinted at this, stating that the joint proposal was unlikely to be accepted by LIHI because it would require the private nonprofit to act as a “quasi-regulatory agency,” which would be “fairly intensive.”

Douglas County PUD’s cooperation would also be required for the proposal to work.

“LIHI would have to be willing to enforce the additional conditions, and Douglas PUD would need to be amendable to that. The easier approach would be to deny certification,” said Garrity.

Garrity declined to comment further, saying only that to characterize the joint proposal from WDFW, CRITFC and the Yakama Nation as part of a negotiation with LIHI would be inaccurate, because LIHI—being a private nonprofit that sets its own standards—was under no obligation to negotiate.

“This is not a negotiation. It’s really their [LIHI’s] choice,” said Garrity.

From Portland to Portland

Though based in Boston, LIHI has its roots on the West Coast. It was first incorporated in California in 1999. The group moved to Oregon, where it briefly had offices in downtown Portland, before moving operations to Portland, Maine, where it was run for years from the house of its then executive director, according to government records.

During its early years LIHI had financial difficulties, according to a 2016 white paper written by the organization for the HydroVision International conference held that year in Minneapolis.

HydroVision International is a leading conference for the hydropower industry.

According to the white paper, while certifying larger dams was profitable for the nonprofit, certifying “smaller facilities did not fully cover the Institute’s expenses.”

LIHI makes its money largely by charging dam owners to certify their dams.

LIHI responded to its early financial problems by raising its application fees and requiring yearly fees for continued certification. These changes helped raise the nonprofit’s revenue, according to the white paper.

LIHI’s Ames says her nonprofit’s business model in no way affects its decision to certify a facility. As proof, she notes LIHI turns down about 20-40% of the applications they receive.

“We are a nonprofit organization, not a for-profit organization,” said Ames. “We are mission driven and it would undermine our program to certify things that did not actually meet our criteria. A project must meet either straight up or conditionally our science-based definition of low impact.”

In Oregon, LIHI certified dams include the Pelton Round Butte Hydroelectric Complex on the Deschutes River. That dam’s operation has come under fire from sport fishers who claim it has led to negative conditions for fish downstream. The dam is approved to sell power on Oregon’s REC market.

The three Washington dams currently certified by LIHI include the Skagit Dam in Whatcom County northeast of Seattle. A 2021 investigative report from KING5 News found that certification for the dam relied on outdated science.

Groups in favor of certifying the Wells Dam include the Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation, which, like the Yakama Nation and WDFW, is a co-manager on the dam’s conservation plan. The Colville Tribes have a 5.5% share of the electricity from the Wells Dam. Douglas County PUD markets the Tribes’ share of the dam’s power, according to a February 2024 press release from Puget Sound Energy promoting its purchase of Wells Dam hydropower from the Colville Tribes and Douglas PUD.

In July, 15 conservation organizations joined WDFW, CRITFC and the Yakama Nation were joined in their opposition to certifying the Wells Dam.

Columbia Riverkeeper has led the effort.

“There’s absolutely nothing low impact about a 60-year-old hydropower facility that drowned 25 miles of the Columbia River and causes migration problems for salmon. It’s just ridiculous,” Miles Johnson, legal director for Columbia Riverkeeper, told Columbia Insight.

Glad someone is watching. Thank you

This is a great article. In addition to explaining LIHI it clarifies the remarkable ecosystem of organizations strategizing and cooperating to advocate for the fish. And it explains the economic motivations for an operator to pursue the LIHI certification.