Chasing Wildlife Secrets, a new book by Scott McCorquodale, offers a firsthand account of the lives of professional wildlife biologists

Helicopter darting: The author of a new book demonstrates a common technique for capturing elk for research. Photo: B. Berry

September 18, 2025. Following is an abridged excerpt from Chasing Wildlife Secrets: A Biologist’s Journey, by Scott McCorquodale, recently published by Washington State University Press. The book is available online, at bookstores nationwide or directly from the publisher.

“There she is.” “Chirp, chirp, chirp….”

The voice on the helicopter’s intercom belonged to Jess Hagerman, our exceptional wildlife capture pilot. The audible electronic “chirps” were emanating from a GPS-equipped collar around the neck of a female elk somewhere below and ahead of us.

The mission was a familiar one. Locate a series of elk wearing the GPS collars we had deployed a year or two earlier. Each collar contained a bounty of sequential location information on the elk’s travels in the form of GPS waypoints. To access the data, we had to recapture each elk and retrieve the collar.

It was a typical late winter day in the Nooksack River country of northwestern Washington. The morning was cool, damp, and misty, with wispy bits of fog surreally blanketing the bottomlands. The snowline was another thousand feet up on the ridge above us. The cold, moist air blowing through the openings on the right side of the helicopter, where doors usually hung, stung our faces; for darting elk, we always removed both doors on the pilot’s side.

Above my head, the sound of the Jet Ranger’s turbine engine was a deafening roar, and I could detect the familiar pungent odor of Jet A aviation fuel combustion.

I checked my rigging—a four-point harness and a tether connecting the harness to the seat frame—and adjusted my gloves and helmet. The adrenaline rush of the chase would come soon.

“Chirp, chirp, chirp….”

The signal from the collar grew louder as Jess used the antenna mounted on the nose of the helicopter to hone in on this particular elk’s direction and close the distance between us.

“This might be tough,” Jess said over the intercom as we both viewed the nearly continuous blanket of forty-year-old conifers below and around us.

Darting elk in the open country of eastern Washington was generally straightforward, but this was Nooksack. Always tough. Clear-cuts were the best areas to work in these forested western Washington landscapes, but there were no clear-cuts near this elk.

“Wait a second,” Jess said as he sped forward and banked to our right, momentarily ignoring the direction of the collar’s signal. “There,” Jess said as we approached a small opening in the sea of trees—a lone gravel pit along one of the forest roads crisscrossing the area. “Not sure if she’ll cooperate, but this is our only chance.”

Jess flew quickly back toward the signal until he was sure we’d flown past the elk. He then banked sharply, sliding behind her, and putting the elk between us and the distant gravel pit.

The author aboard a Jet Ranger piloted by veteran wildlife capture pilot Jess Hagerman. A full day of this work typically yielded 15 to 20 captured elk. Photo: J. Gaydos

As we got closer to her and the “chirp, chirp, chirp…” increasingly became a loud “thud, thud, thud…” in our earphones, we got our first glimpse of her as she moved gracefully through the trees below. Game on.

Patient as ever, Jess kept gently pressuring her to move in the desired direction. He did this skillfully by turning her slightly left, then right, then left, constantly redirecting her with the aircraft and keeping her line of travel toward the gravel pit. Five hundred yards, then four hundred yards, then three hundred, and two hundred. She had the advantage, and our plan was a longshot. But for now, she was doing what we wanted. We saw her on and off, flashing through tiny gaps in the forest, but the signal always betrayed her location.

At one hundred yards, Jess spoke over the intercom, “Heck, this might just work. Get ready.”

With a dart already in my rifle, I put my right foot out onto the helicopter’s skid and leaned out the back seat doorway until the safety tether on my harness was taut. She was still on the line we wanted, due only to Jess’s skillful maneuvering. I worked the bolt to put a live charge into the rifle’s action and began to feel the effects of increasing adrenaline.

At twenty yards from the edge of the gravel pit, Jess said, “Here we go,” as he closed the distance for the final hard push to get her into the gravel pit. I flicked the safety off and brought the rifle into a shooting position. She was just in front of us, slightly forward and right of Jess’s door.

As she broke into the open, Jess slightly dropped the collective that controlled the aircraft’s lift, and we dropped almost next to her as Jess flared the helicopter and barked, “NOW!” Sensing her vulnerability on the open ground, she was running full-out—as fast as an elk can go. She was at my two o’clock position, fifteen feet below me and ten feet to my right.

There was no time for precision aiming—one chance, no hesitation. I pulled the sights onto her upper left hind leg and squeezed the trigger. “Pop!” The dart flew true, and as I saw it hit her perfectly in the thigh, I shouted, “Dart in,” into my helmet mic; Jess parroted, “Dart in,” as he pulled back on the cyclic and up on the collective, which quickly pitched the nose up as the line of trees on the other side of the gravel pit rapidly loomed in front of us.

Seconds later, the elk made cover at the tree line just before the tree line sped by below us in a blur as we cleared it. She had been in the opening for ten seconds.

Now we were back to tracking her mainly by the collar. Typically, it took seven to ten minutes for the drug to put an elk on the ground, sedated. We faced a significant challenge—the same one we always had. We needed an open space to set the aircraft on the ground (or manage a one-skid landing on a stump) fairly close to where she ended up so that I and my “mugger”—who sat to my left in the back seat—could get out and perform the necessary hands-on tasks with this elk. We needed less space than for darting, but it had to be someplace with enough clearance for the rotor blades to accommodate a safe landing—or at least touch a skid to the ground.

At about five minutes, she had stopped moving as the drug dulled her cognition. We could barely see her through the trees, and at about eight minutes she wobbled and went down.

Jess took a GPS position, and then the search for a landing zone began in earnest. We were too far from the gravel pit for that to work—the roads below us were the best bet. As we backtracked on one close to her, we followed it around a corner and discovered a gap in the roadside alders that was just big enough for landing with a completely vertical descent.

As the aircraft settled straight down onto its skids, we back-seaters slipped out of the open doorway with our gear and dropped to one knee next to the skids. I extended my arm to Jess’s open doorway and popped my thumb up where he could easily see it—all clear. Jess made eye contact, nodded, and immediately powered up again, as he lifted straight up through our little gap in the trees.

It’s not easy to find a sleeping elk in a brushy forest on foot. We knew the general direction, but we were looking for a nonreactive, prone animal in dense cover.

Fortunately, we had an advantage. We’d done this hundreds of times in western Washington. Jess flew to the GPS waypoint he took where the elk had gone to sleep, used the helicopter’s tracking equipment to obtain her precise location, then just hovered there above the trees. We simply had to walk toward the sound of the helicopter’s roaring turbine. Well, “walk” might be understating it a bit—more like bushwhacking through blackberries, devil’s club, and the like. Still, in less than ten minutes we were kneeling next to her, completing all the tasks we had to do, including retrieving the GPS collar and its treasure trove of data.

Forty minutes after darting her, I administered a reversal drug injection to awaken her from a peaceful slumber. Three minutes later, we could see consciousness return to her eyes as they rolled back into their normal position, and a minute after that she was fully alert and up on her feet again. Glancing at us in bewilderment, she quickly pivoted and disappeared back into the cloak of the forest. Mission accomplished. It was time to start all over again with a different elk.

In field studies of elk, deer, moose, and black bears, helicopters and small airplanes were a regular and versatile tool. I flew often—weekly at times, even daily for some projects. By my count, I flew in twelve different helicopter models and at least eight distinct kinds of small, fixed-wing aircraft during my career.

I logged enough hours that, had I been a student pilot, I could have obtained licenses to fly both helicopters and small airplanes. But I was never up there to learn how to fly. I was up there to accomplish tasks like counting animals to estimate their abundance or density, finding animals with radio collars to determine their movements and survival, locating dens of radio-collared bears, or capturing animals to support various research objectives.

Besides the helicopter capture work, I spent many aircraft hours radio-tracking collared animals. To radio-track with an airplane, we attached two antennas, one on each wing strut. We flew along, listening with both antennas as we scanned for collars. When we detected one, we turned while I switched back and forth between the two antennas to get the strongest signal. We kept refining the estimated direction until we could finally fly a tight circle around a tiny area with the signal always staying stronger from the antenna on the inside of the turn—the collared critter was inside that circle, even if we couldn’t see it.

The kind of flying biologists do in support of wildlife research is interesting and exciting—but also stressful and risky. Normal people don’t do stuff like this. Often, our families wished we didn’t do stuff like this.

Helicopter captures were particularly complex efforts—managing a team of people and lots of gear; monitoring weather windows, flight plans, emergency contingency planning; and identifying staging areas and remote refueling spots.

More than once, with a public roadway near an area where we would be capturing elk, we prearranged with local law enforcement or the Washington State Patrol to be prepared to stop traffic if elk headed for the roadway. We tried to think of everything that could happen—make a plan for what we wanted to happen and contingency plans in case something different happened.

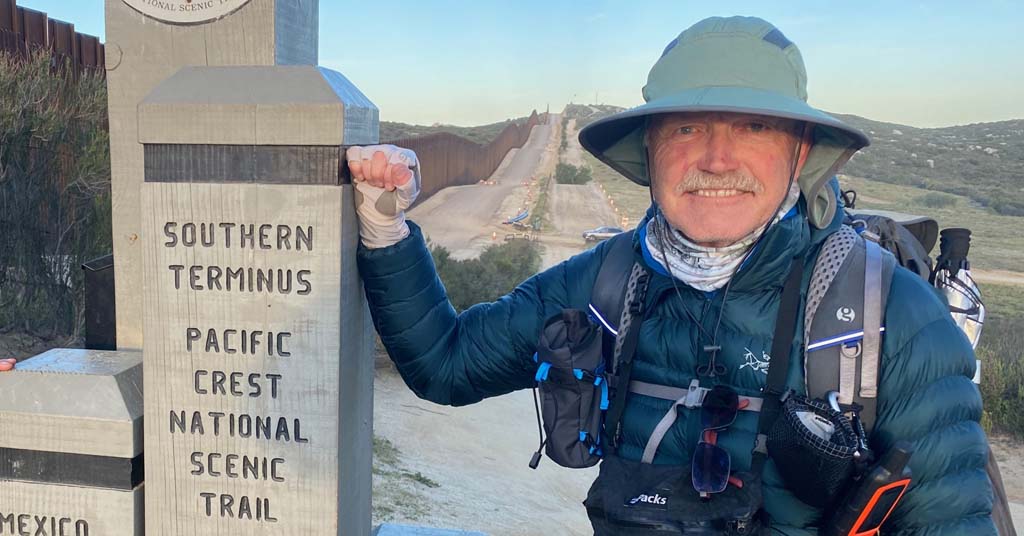

Scott McCorquodale, continuing to cover ground. Photo: Scott McCorquodale/WSU Press

I rarely slept well the night before an operation. I was, after all, responsible for the welfare of my team—and the welfare of the animals we’d be chasing. I both dreaded and loved it.

Technology evolved exponentially over the course of my decades-long career. GPS collars now exist that use satellites to pinpoint an animal’s location accurately and send that information to a desktop computer. A researcher can get such location information two, three times a day—even hourly, if necessary. Over half my career predated such technology.

At one time, we were wowed by a simple VHF radio collar that did nothing but emit a pulsed signal. Radio-tracking animals wasn’t even a widely available option until the 1960s.

Unmanned drones are some of the newest innovations, and wildlife researchers are still learning how to incorporate them. It’s possible that someday activities once requiring a person in an aircraft—at significant risk of harm—will be carried out using a drone flown by someone sitting in a truck or a heated office, watching a video screen.

I enjoyed the flying, mostly—the variety of missions, using so many different aircraft, and in virtually every part of Washington. I was able to see incredible things that are out of reach for most people—and I got paid to do it. I was fortunate, and I knew it.

As a large mammal researcher, flying was just part of the job. Okay—an enthralling part of the job. It was usually rewarding—I saw amazing country almost every time I went up plus other critters besides the ones that were the target of my research—mountain lions, mountain goats, bighorn sheep, and a wolf.

On one fall aerial survey for elk in the Mount Rainier alpine, we saw twenty bears in a two-hour flight. I witnessed more than one bull elk shed its antlers on late winter flights while I watched them from a helicopter.

We learned a great deal about wildlife that we could not have learned without being in the air. It was a unique vantage point for observing the natural world. The work promoted conservation and informed management of Washington’s wildlife. We developed new, innovative tools from data we had to fly to get.

It’s intuitive that flying around at low altitudes in pursuit of wild animals doing their best to avoid capture is inherently dangerous. No sane biologist thinks otherwise. We believed that the chances of an accident were low if we followed our protocols—but we also knew the consequences of any flying accident could be serious. I never approached this work with a cavalier attitude. It was serious stuff. I only got in an aircraft—or asked others to get in with me—when there was a compelling reason. The objectives had to be important and, in my mind, the risks had to be manageable.

I knew people had died doing this kind of work. Smart, careful, skilled people. I also read the study published in 2003 that explored the causes of on-the-job deaths of wildlife biologists. Flying accidents were the number one cause, accounting for over 60 percent of reported deaths. I had no illusions of invincibility. And I wouldn’t fly with people who didn’t take it deadly seriously.

Chasing Wildlife Secrets: A Biologist’s Journey is available online and from Washington State University Press. Reprinted with permission from the Washington State University Press.

Aircraft can be a horribly invasive and disturbing method to collecting data, particularly herd surveys. I’m hopeful that developments in drone, thermal, and even DNA technology will reduce costly and dangerous aircraft use. We are using both of the former to census animals on our private lands and have encouraged ODFW to limit aircraft use to collaring activities. My personal attitude really changed when I witnessed ODFW run elk and deer (on separate occasions) through our fences while censusing.

I hope future wildlife biologists will think more about the health and welfare of the actual animals they want to study by finding less stressful and invasive ways to collect this data. Using scats has its advantages. A lot of info can be learned from scat such as data needed for studies of genetic diversity and data on what the animals eat. Hormones and stress levels may also be found in scats. Photo traps are another less invasive method if used carefully. One of the worst has to be putting collars around the neck of wild animals. A collared elk calf in the Blue Mts elk study died after its collar became stuck in a fence. Another was abandoned by the mother after the horrible experience of having a calf collared. Do we really have the right to collar wild animals? From having horses, I know that horses love the time when we take all of the riding equipment off of their heads, faces and backs. It seems like change is coming as more younger people and women become wildlife biologists. Hopefully the ethical issues are now part of the the required curriculum too.