The public wants species protection but lawmakers are struggling with dwindling funds, higher fees and a biodiversity crisis

Budget trap: Everyone wants healthy wildlife populations. Not everyone wants to pay for them. Photo Illustration: Nicole Wilkinson

By K.C. Mehaffey. July 24, 2025. If a government’s budget is a statement of its values, consider this: this year, legislatures in Oregon and Washington dedicated roughly 2.4% of their total 2025-2027 biennium budgets to all of their natural resource agencies combined. In Idaho, about 4.6% of the state’s total fiscal year 2026 budget will go to natural resources.

The state departments of fish and wildlife—or fish and game in Idaho—make up only a fraction of those slices of the budget pie.

Natural resource funds also cover the costs of agencies that manage state parks, outdoor recreation, water resources, agriculture, environmental quality, forestry and many smaller state entities—such as the Puget Sound Partnership in Washington or the Wolf Depredation Control Board in Idaho.

State officials and nonprofit organizations say they think the public in the Pacific Northwest would be surprised at how little their states spend on natural resources.

Facing inflation and lower revenues from taxes, legislatures in Oregon and Washington this year raised user fees and made significant cuts to their state fish and wildlife agency budgets. The Idaho Department of Fish and Game—which relies solely on the sale of hunting and fishing licenses and federal funds—got a small bump in funding.

But with federal cuts looming and stagnant or decreasing participation in hunting and fishing, officials from all three state agencies say they’re deeply concerned about their budgets in the coming years and decades.

“We know with climate change and with all the federal impacts coming down the pike that we have a hard future ahead of us,” Brandon Bean, Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife’s budget officer, told Columbia Insight.

Wildlife budgets

The Idaho Department of Fish and Game is self-sufficient, funding its entire department with revenue from the sale of fishing and hunting licenses, and with matching federal and non-federal grants.

“We have been fortunate to escape some of the cuts our sister states have seen this year,” Jon Oswald, IDFG Administration Bureau Chief told Columbia Insight.

He said that people who don’t hunt or fish are increasingly using IDFG resources—like paddleboarders accessing the water on state boat ramps—but the state hasn’t attempted to monetize that use. At least not yet.

While Idaho gets none of its funds from the state general fund, Oregon gets about 13%, and Washington receives roughly 40% from its state’s general fund.

Ken Loffink. Photo: ODFW

That reliance on general funds means that inflation and projections for reduced tax revenues this year took a toll on Oregon and Washington’s fish and wildlife budgets.

Compared to the 2013-2015 budget, the new Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife budget reduces its staff by almost 100 full-time employees, ODFW Chief Operating Officer Ken Loffink told Columbia Insight.

This biennium, the agency is reducing its budget by $8.5 million and will enact a fee increase for fishing and hunting beginning in 2026, which will be rolled out incrementally over six years.

“Those reductions were necessary just to balance our expenditures with revenues,” said Loffink.

He added that inflation has increased costs by roughly 25% over the last decade.

“At the same time, our expectations on the department continue to grow and challenges from climate change are increasing,” he said.

The Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife is in a similar situation.

The Washington Legislature this year dealt with a long history of being underfunded—ever since the 2008 recession. Lawmakers fixed this longtime structural deficit by raising hunting and fishing licenses by 38%—the first increase since 2011—and making deep cuts elsewhere.

“Essentially, we’re being asked to do less,” said Bean, WDFW’s budget officer.

A June email from WDFW Director Kelly Susewind to staff—which agency officials sent to Columbia Insight—shows the extent of those cuts.

Under the new budget, WDFW is losing up to 197 positions by laying off 29 people and by not filling as many as 168 vacant positions. If all go unfilled, the department will lose 7.5% of its workforce, WDFW spokesperson Samantha Montgomery told Columbia Insight.

Susewind’s email lays out a whole list of cuts, ranging from the closure of a hatchery and the loss of aquatic lands restoration grants to reduced funding to respond to wildlife diseases and treat forest fuels to prevent wildfires.

Bean said the current budget sets the agency back, but also enables WDFW to live within its means.

Looking at the three states, Zach Lowe, executive director of the Western Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies, said they are representative of the many ways fish and wildlife agencies are funded across the West.

Some states have big departments, big budgets and big expectations, while others have smaller departments with fewer obligations, and can rely largely on hunter and angler fees.

Idaho, for example, has a separate agency that works to preserve and restore species listed under the Endangered Species Act. Washington and Oregon manage marine species in addition to land and freshwater animals. Their reliance on general funds reflects the desire of state residents who don’t hunt and fish to preserve wildlife.

But Lowe believes comparing budgets as though they are report cards on state values makes little sense.

“It’s not even comparing apples to oranges. It’s more like apples to bran flakes,” he said.

Still, Bean noted that while it may not be a fair comparison, a state’s budget is still a statement of its values, especially when looking at the state-generated general fund.

In Washington, 2.4% of its total budget goes to natural resources, but those agencies get only 1.4% of the state’s general funds, with a fraction of that going to WDFW.

“I would say Washingtonians love conservation. They love their natural resources. They love the value we bring both economically and intrinsically,” said Bean.

He thinks the public would be surprised to know that such a small portion of the state’s funds support these agencies.

Funding gaps

Throughout Oregon’s long legislative session this year, Jennifer Fairbrother, legislative and policy director for the Native Fish Society, followed the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife budget and proposed cuts.

A hunter and angler herself, Fairbrother said a significant reliance on license fees and sportsmen taxes likely has an impact on the agency’s focus.

“We’re spending more on hatcheries than we are for the entire [ODFW] Wildlife Division,” she said.

Jennifer Fairbrother. Photo: Native Fish Society

Her organization is concerned that a large part of Oregon’s deficit is being filled by cutting the monitoring that helps ensure sustainable salmon and steelhead fisheries.

“This wasn’t adequately funded even before the cuts,” she said. “All these nongame species that are needing our focus and resources—they get the short shrift again and again.”

While the bulk of funding goes to hatcheries or protection of wild salmon and game animals, Oregon has identified nearly 300 “Species of Greatest Conservation Need” that get far less attention—and funding.

Species like Columbia spotted frogs, American marten and Lewis’s woodpecker “are defined as having small or declining populations, are at-risk and/or are of management concern,” according to the Oregon Conservation Strategy.

The list includes 17 amphibians, 58 birds, 29 mammals, five reptiles, 60 fish, 62 invertebrates and 63 plants and algae.

In Washington, Mitch Friedman, executive director of Conservation Northwest, said the state’s structural deficit from 2008 led state lawmakers to order up a third-party audit of the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, and to form WDFW’s Budget and Policy Advisory Group (BPAG), of which he is a member.

The hunters, fishers and conservation groups that agreed to sit on BPAG thought they’d be fighting over where the money should be spent, he told Columbia Insight, “but we all got along.”

The department passed its audit, and the advisory group agreed that WDFW needed to get its structural deficit fixed and develop a plan to preserve the roughly 280 at-risk species in its State Wildlife Action Plan.

The plan is a good one, he said, but although the plan was adopted 20 years ago, “only about 4% of the steps identified get implemented because the money isn’t there.”

Friedman said the legislature provided only half of the agency’s request for protecting biodiversity, and then cut that by $1 million a year in the latest budget.

“We’re better off than we were three years ago, but it’s only about half of what it should be,” he said.

Critical role of hunter and angler fees

Lowe of the Western Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies said across the country hunters make up less than 5% of the population but pay upward of 80% of state fish and wildlife agency budgets.

“It’s a disproportionate benefit to wildlife conservation,” he said.

The Congressional Sportsmen’s Foundation tracks how much fish and wildlife agencies in each state get from fishing and hunting licenses and two federal funds known as Pittman-Robertson and Dingell-Johnson.

Named for the lawmakers who sponsored the legislation in 1937 and 1950, the bills enacted nationwide taxes on everything from boats and guns to fishing rods and ammunition to help states pay for fish and wildlife conservation.

The foundation’s one-page fact sheets rank Oregon 11th, Idaho 12th, and Washington 13th highest in total funds received from user fees.

Eric Crawford. Photo: Trout Unlimited

Marie Neumiller, assistant manager of Northwestern states for the Congressional Sportsmen’s Foundation, said together, the hunting and angler fee system is called the American System of Conservation Funding. Her organization is a big supporter.

“We strongly believe in that user-pay, public-benefit system. It’s something we’re very proud of,” she said.

Also a member of BPAG, Neumiller said other methods for funding the conservation of fish and wildlife have been tried, but “those don’t gain as much traction or support as you see in the hunting and fishing communities.”

Eric Crawford, north Idaho field coordinator for the Idaho Council of Trout Unlimited, told Columbia Insight that relying completely on user fees and taxes is successful in Idaho.

“But Idaho does not have the population that Washington and Oregon have, and so it’s a little bit different. With population growth comes incredible impacts on fish and wildlife species,” he said. Those states have larger needs, and larger public expectations. In Idaho, “Most of these species can prosper and have very little interaction with humans.”

Still, he noted, participation in hunting and fishing is dropping nationwide.

At IDFG, Oswald said his agency’s reliance on hunter and angler fees and taxes works, but the stagnant sale of hunting and fishing licenses in Idaho will eventually chip away at their budget. At the current trajectory, he said, expenditures will eventually outpace revenues.

In Washington and Oregon—where the state populations are higher and impacts to wildlife are greater—state officials say hunters and fishers can’t carry the full burden of conserving fish and wildlife.

On top of troubles with their state budgets, fish and wildlife agencies know they may be facing deep cuts in funding from the federal government.

Crawford said that the Pacific Coastal Salmon Recovery Fund, under NOAA Fisheries, provides a lot of funding for salmon, and is targeted to be defunded. But recently enacted state budgets don’t account for these potential cuts.

“Right now, there’s so much noise in the federal system it’s hard to know what’s real and actionable,” said Bean.

Neumiller said she’s concerned about more than cuts in federal funding.

“In our states, there’s a lot of shared management, and as those budgets get cut, that’s gone,” she said.

A better way?

Oregon State Rep. Emerson Levy (D-Bend) is co-chair of the Joint Ways and Means Subcommittee on Natural Resource.

She said Oregon is preparing to receive a lot less money for natural resources—and less coordination—from the federal government. There’s also competition with other state agencies for funds.

She said for a time—thanks to funding for wildfires—Oregon spent roughly 5% of its total budget on natural resource agencies, but that’s dropped to about 2.4%.

“There’s ultimately a cost in not investing in our natural resources,” she told Columbia Insight. “We’ve done a lot with a little, but I think it warrants further investment.”

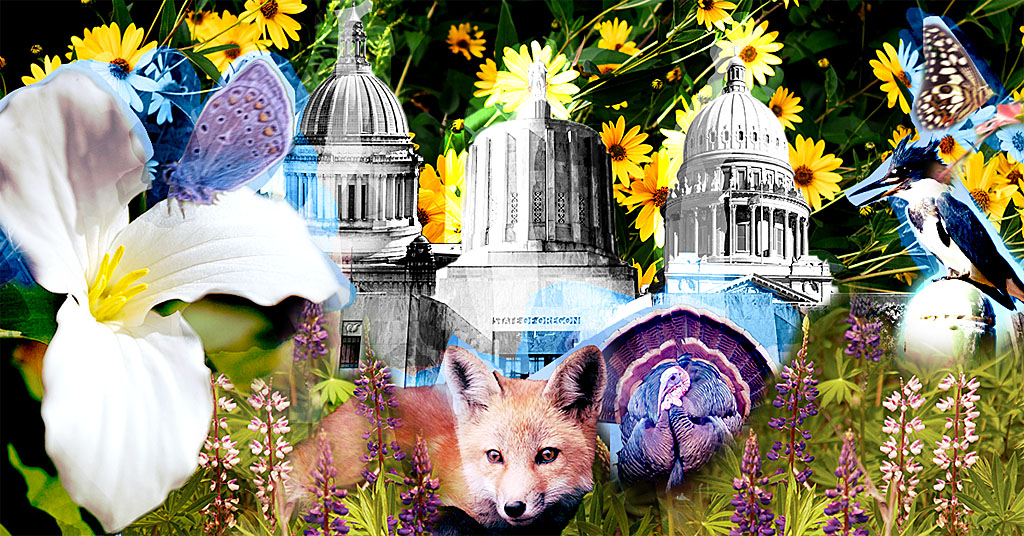

Photo illustration: Nicole Wilkinson

ODFW’s Loffink believes there’s a need to find new sources of funding.

But where will the money come from?

This year in Oregon, lawmakers introduced HB 2977—which sought a 1.25% increase to the transient lodging tax, with a large portion of the funds earmarked for ODFW to spend on species conservation.

Levy calls the bill a “game changer,” and while it did not pass this session, she expects it to reemerge next year.

But creating new taxes is tough.

Friedman, of Conservation Northwest, said in previous sessions a Washington lawmaker tried to initiate a state tax on hiking and camping gear to help fund species conservation, but got pushback from a major recreation outfitter in the state and the effort failed.

There have also been national efforts to resolve the problem of underfunded fish and wildlife agencies.

Neumiller, of the Congressional Sportsmen’s Foundation, said to keep the backbone of funding flowing, her organization urges hunters and anglers to continue to participate: teach their kids, invite friends and keep buying licenses even when life gets busy.

ODFW spokesperson Michelle Dennehy said federal lawmakers were considering a national a bill known as Recovering America’s Wildlife Act, but those efforts have fallen by the wayside.

At the Western Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies, Lowe suggested that donating directly to fish and wildlife agencies could be an option.

“When you make donations to them, they are good about leveraging those funds. They can turn one dollar into four really effectively,” he said.

Lowe said surveys have found that state fish and wildlife agencies get high marks from the public, with between 60% and 70% of state residents saying they are trustworthy.

“It’s numbers that corporate America would kill for,” he said, adding, “Our state fish and wildlife agencies have demonstrated a lot of trust, and a really strong track record of serving the people they represent really well.”

As resources and activities for wildlife conservation dwindle, however, it could become increasingly difficult for state agencies to maintain that hard-won public trust.