Voters who assumed Washington’s new governor would follow his predecessor’s game policies are dismayed. Others are rejoicing

No longer eye to eye: Then Washington Gov. Jay Inslee (right) confers with then Attorney General Bob Ferguson at a 2019 event in Seattle. Photo: AP Photo/Ted S. Warren

By Nick Engelfried. June 5, 2025. When longtime wildlife advocate and Spokane resident Ronald Reed learned Wash. Gov. Bob Ferguson was sending two of former Gov. Inslee’s nominations to the Washington Fish and Wildlife Commission back to the drawing board, he thought maybe there had been a mistake.

“I wondered what in the world he was doing,” says Reed, a former board member of Washington Wildlife First.

Reed had met with Ferguson during the latter’s 2024 bid for the governor’s office, and was impressed with him as a candidate. Reed and his wife later donated $3,500 to the Ferguson campaign.

“That may not seem like a huge amount, but it was to us,” says Reed.

Soon, though, he wondered if the new governor was the person he had believed Ferguson to be.

At issue were two seats on the Washington Fish and Wildlife Commission, a body with authority over everything from hunting regulations to state fish hatcheries. The Commission is composed of nine members appointed by the governor to six-year terms, during which they oversee the Department of Fish and Wildlife.

In early January, the outgoing Inslee asked the State Senate to approve two appointees well liked by environmental groups: rancher and former park ranger Lynn O’Connor, and marine mammal scientist Dr. Tim Ragen.

It came as a shock to Reed when Ferguson not only asked the Senate to return Ragen and O’Connor’s nominations, but to put forward two appointees to the commission seen as much more friendly to hunting and fishing interests.

“Wildlife advocates feel betrayed by what happened,” says Claire Loebs Davis, Washington Wildlife First’s board president.

Not everyone is dissatisfied with Ferguson’s choices.

“We would say, overall, this is a good outcome given the cards we were dealt prior to this,” says Ed Johnstone, chair of the Northwest Indian Fisheries Commission, which prefers Ferguson’s appointees.

Still, reactions from within the environmental community point to tensions between prominent green groups and Ferguson’s actions in office, at least as regards wildlife management. Reed, for one, decided his support for the governor had been misplaced.

After the new appointments were announced, Reed called the Ferguson campaign and asked for his donation back. The campaign complied.

“What Ferguson’s doing as governor is not what I was contributing toward,” says Reed. “If I’d known during the campaign he would govern like this, I would have been looking real hard for someone to run against him.”

Juggling appointments

Over the last 12 years, Washington wildlife groups got used to having an ally in the governor’s office.

Former Governor Inslee put the environment at the center of his agenda, helping shepherd a long list of green bills through the legislature. Most had to do with climate and energy, but Inslee’s actions around wildlife also earned high marks from green groups.

Inslee’s appointments to the Fish and Wildlife Commission included biologists Lorna Smith and John Lehmkuhl, environmental attorney Melanie Rowland, and Tim Ragen, who previously served as director of the U.S. Marine Mammal Commission.

Caught in crossfire: Gov. Jay Inslee appointed Tim Ragen to the Washington Fish and Wildlife Commission. Gov. Ferguson pulled his appointment. Photo: Tim Ragen

Ragen’s appointment was especially significant for the crisis facing the Salish Sea’s southern resident orcas.

“Dr. Ragen has focused his career on recovering endangered species,” says Davis. “There was no one better situated to help us navigate the challenges we face rebuilding orca and other wildlife populations in Washington.”

In January, Inslee reappointed Ragen for another term. He also chose Lynn O’Connor, who drew statewide attention last fall after asking wildlife officials to spare the life of a bear that attacked her and her dogs, to replace Commissioner Molly Linville. Linville was seen as one of the body’s most hunting- and fishing-friendly members.

These appointments continued a trend under Inslee of shifting the balance of the commission away from hunting, fishing and ranching interests that historically dominated it.

“It’s not that those interests shouldn’t be represented,” says Emma Helverson, executive director of the Wild Fish Conservancy. “They absolutely should be. But what was missing until recently were people with scientific expertise who could bring an unbiased view of wildlife management to the table.”

Ragen and O’Connor hadn’t yet been confirmed by the Senate when Ferguson took office.

Instead of moving that process forward, Ferguson pulled their appointments.

In their places, he reappointed Linville and named former commercial fisherman and high school science teacher Victor Garcia to replace Ragen.

Ferguson also reappointed Jim Anderson, another member friendly to hunting and fishing interests, whose term was expiring.

Hunting and fishing groups praised Ferguson’s choices.

“All three commissioners represent varied and vital expertise and familiarity with Washington’s wildlife and natural resource management,” says Dan Wilson, co-chair of Washington Backcountry Hunters and Anglers. “While it’s unlikely we’ll always be in lockstep with their policymaking decisions, it is clear these individuals possess the knowledge and skill sets to make critical decisions for the long-term interest of sustainable wildlife management in Washington.”

Environmental groups have largely withheld judgment on Garcia, who is a new face on the commission and something of an unknown quantity.

“We want Victor to have the freedom to show us who he his through his service on the commission,” says Davis. “Of course, we’ll be watching closely what he does.”

However, Ferguson’s other two appointments and the departures of Ragen and O’Connor have left wildlife advocates dismayed.

“I’m afraid these choices will mean a reversal of progress we’ve made in recent years,” says Davis. “The governor is taking us back to when hunters and fishers firmly controlled wildlife policy in our state.”

Contentious votes

When Davis founded Washington Wildlife First in 2021, it was partly to engage more people in decision-making processes affecting wildlife that can seem opaque to the public.

“Not many Washingtonians really understand the Fish and Wildlife Commission, what it does and how powerful it is,” says Davis. “Most would also probably assume, like I once did, that wildlife policy in Washington is pretty progressive. But we’ve found when we describe many of the policies that are actually in place to people, they are appalled.”

Davis cites polls her organization commissioned showing, for example, that 80% of Washington voters oppose hunting bears during the spring cub season, a practice allowed until a few years ago. For decades, environmental groups pushed to change policies like this without much success.

“There’s still a lot of scientifically outdated, anti-carnivore sentiment out there driving state policy,” says Josh Rosenau, director of policy and advocacy for the Mountain Lion Foundation, which supports stricter rules for hunting predators.

Back in the game: Under Gov. Ferguson’s administration, hunters are seeing more opportunities to influence Washington wildlife policy. Photo: Pashiya Sandum/WDFW

Things began to change as Inslee slowly filled the commission with new members.

The commission voted in 2022 to end the spring black bear hunt, and in 2024 chose not to downgrade the protected status of wolves. These decisions earned cheers from many environmental groups, but other stakeholders saw a drift away from prioritizing economic and cultural uses of fish and wildlife.

“We’re salmon people,” says Johnstone of NWIFC, which represents 20 federally recognized tribes. “We have to have fish for our living culture, our food, our economy and our way of life.”

NWIFC took a skeptical view of Inslee’s recent Fish and Wildlife Commission appointments.

“What some of these individuals want isn’t conservation, it’s preservation,” says Johnstone. “That’s a huge difference. Preservation means keeping the minimum viability of a species alive so you can see them out in the ecosystem occasionally. We’re not interested in that.”

Tribal nations and environmental nonprofits have partnered on many initiatives to restore animal populations in Washington.

But debates on the Fish and Wildlife Commission expose schisms between tribes and at least some wildlife groups.

One such point of contention is over salmon hatcheries. A 2018 decision by the commission dramatically increased hatchery fish production in Washington, based partly on the argument that it would lead to more food for the Salish Sea’s orcas. Tribes and the commercial fishing industry supported the new policy.

Wildlife advocates say more hatcheries could actually harm the southern resident orcas. Hatchery fish compete with wild salmon and may impede the recovery of native salmon runs in the long term.

Pop up: An orca giving the people what they want. Photo: Chuck Thompson

Ragen emerged as a hatchery skeptic on the commission.

“We are deeply concerned that without Dr. Ragen’s expertise, future policy decisions may lack the scientific rigor required to confront the complex, interconnected threats facing both southern resident killer whales and the wild salmon they rely on,” says Shari Tarantino, executive director of the Orca Conservancy, which focuses on restoring the southern residents.

Ferguson’s office says Ragen’s departure will not affect orca conservation.

“We appreciate Tim Ragen’s service, but suggesting the commission cannot continue its work to protect southern resident orcas is, frankly, silly,” says Brionna Aho, the governor’s communications director. “The Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife and many other natural resource agencies have expertise on this issue, and our state work to protect orcas remains a top priority.”

Still, orca advocates worry about how Ferguson’s appointments will affect the commission’s balance at a time when the hatchery issue has become a flashpoint between the scientists whom wildlife groups largely support, and tribes and other stakeholders aligned with members like Anderson and Linville.

“This division shows how wildlife management in Washington is not just ecological, it’s political,” says Tarantino. “This is especially dangerous in a time when wild salmon and the southern residents are in steep decline.”

Tackling “dysfunction”

Ferguson says his appointments will help address a perception that the Fish and Wildlife Commission as it currently operates is dysfunctional.

A report released last December by the William R. Ruckelshaus Center, at the request of the Washington legislature, cited dysfunction as a key theme emerging from more than 100 interviews with stakeholders who interact with the commission.

“The Ruckelshaus report raised serious concerns about the commission, and we believe these individuals will help to address those issues,” Ferguson said in a statement announcing his appointments of Anderson, Linville and Garcia.

Wildlife advocates aren’t so sure.

“Everyone’s wielding this report to defend whatever decision they want to make,” says Helverson of the Wild Fish Conservancy. “But then the governor reappoints two of the same people who served on the commission throughout this dysfunction.”

There’s also disagreement about what a functional commission really means.

“If it means things move quickly, with little disagreement, then Gov. Ferguson has done a lot to bring us back to that point,” says Davis. “But if it means a commission with a diversity of opinions where people debate issues, ask questions and vote according to their consciences, we’re now moving farther from that goal.”

Tribal stance

Another issue is a lack of clarity about the commission’s relationship with Tribes.

“There is a government-to-government, sovereign-to-sovereign relationship between the U.S. and State of Washington and tribes,” says Johnstone. “But under the Fish and Wildlife Commission the way it’s currently constructed, that relationship is barely recognized.

“You have nine individuals with their own constituencies and views that don’t necessarily match the duties of that government-to-government relationship.”

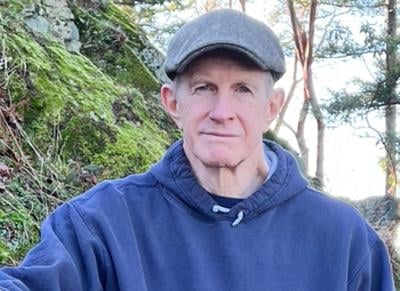

Ed Johnstone: Photo: Northwest Indian Fisheries Commission

One approach to addressing issues within the commission would be to dissolve it, making the Department of Fish and Wildlife a cabinet-level agency in the governor’s administration. Johnstone favors this option.

“It needs to be under the governor’s office, so a true government-to-government relationship is in place,” he says.

Such a change would require moves from the state legislature. This year’s legislative session ended without action on the issue, leaving the current structure of the commission in place for at least another year.

What will Ferguson’s appointments to the commission mean for wildlife during that time? One thing almost everyone agrees on is the new governor’s appointments represent a significant break with the trend under Inslee.

“Molly Linville and Jim Anderson, at least, have been solid supporters of the exploitation of wildlife with very few constraints,” says Davis. “That is the record Gov Ferguson has chosen to reward, so expect to see it continue.”