Lower catch limits for fish and compromised maritime safety are just some of the ways Trump’s proposed budget could weaken the Pacific Northwest

Letting go: An Oregon Sea Grant worker prepares a sevengill shark in Willapa Bay, Wash., for tagging. Federal funds for the program may soon be eliminated. Photo: OSU Media/Oregon State Productions

By Nathan Gilles. May 22, 2025. The Trump administration wants a leaner federal government. To get there it’s slashing funding for science.

One federal science agency going under the figurative chainsaw is the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. NOAA is targeted for deep cuts in the President’s fiscal year 2026 budget proposal, which also calls for the elimination of whole programs and one NOAA line office. A White House press release claims the president’s budget will “gut a weaponized deep state.”

If approved by Congress, the move would hamstring an agency already struggling with fleeing staff and funding restrictions.

Scores of NOAA employees have been fired or opted for early retirement. NOAA grant holders at universities are starting to see those grants terminated. And NOAA contracts over $100,000 are reportedly being personally reviewed by Secretary of Commerce Howard Lutnick. NOAA is part of the Department of Commerce.

The cuts, however, won’t just affect scientists. In fact, to say NOAA funds science is like saying General Motors builds cars, without mentioning the numerous events and destinations to which those cars take people.

I know this because I was previously employed at Oregon State University, where I worked on two NOAA-funded programs.

NOAA has been accused by the political right of not funding applied science, but the evidence suggests something else entirely.

NOAA not only funds applied science, but that science is often tailor-made for specific end users, be they communities or businesses.

Think of NOAA’s work like tech support that also advances science and comes with a watchful eye on the health of our atmosphere and oceans.

You don’t have to look far to find examples of NOAA’s bespoke science.

In the Pacific Northwest, cuts to NOAA are likely to negatively impact everyone from fishers and crabbers to rural communities responding to climate change.

Cuts to NOAA are also likely to make it harder to track and respond to environmental harms, including climate change impacts, as well as threats to the health of our region’s fisheries and the safety of the food it produces.

A full exploration of the cuts and programs slated for elimination is beyond the scope of this story. This article covers just a handful.

Apps, data and buoys

The Trump administration is proposing cutting nearly $1.7 billion from NOAA’s budget for the fiscal year 2026, according to a budget proposal leaked to the San Francisco Chronicle and other news outlets. For reference, NOAA’s budget was $6.7 billion in fiscal year 2024.

The proposed budget calls for the elimination of full programs. One of them is the Integrated Ocean Observing System Regional Observations program.

In the Pacific Northwest, the program funds the Northwest Association of Networked Ocean Observing Systems, or NANOOS. Housed at the University of Washington, NANOOS maintains a network of high-tech buoys along the Oregon and Washington coasts that measure multiple metrics, including wave height (important for safe navigation), the amount of dissolved oxygen in ocean water (important for monitoring low-oxygen “hypoxic” events that can lead to fish die-offs) and the pH level of ocean water (important for monitoring ocean acidification impacting shellfish).

The buoys even measure ocean water concentrations of domoic acid, a neurotoxin that can build up in shellfish and lead to illness or even death when consumed.

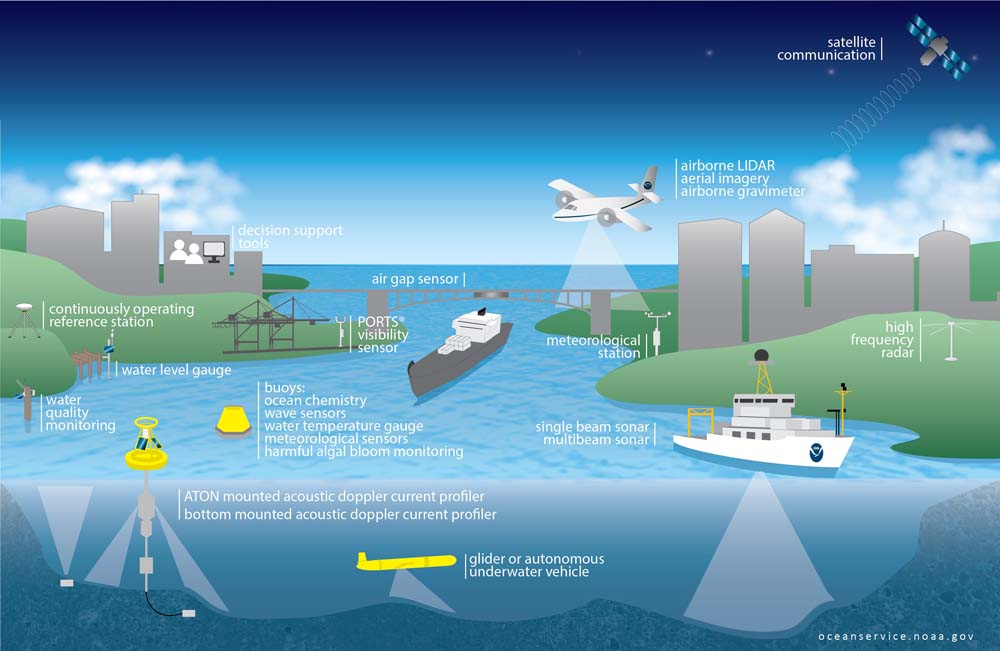

Coastal intel: NOAA’s vast network of radars, satellites, buoys, tide gauges, ships, aircraft and supercomputers keep tabs on information used to predict changes in climate, weather, oceans and coastlines. Infographic: NOAA

The data from the NANOOS buoys are then combined with satellite, weather station and other data sources, calibrated through computer models and sent to computer and smartphone apps created for specific end users. NANOOS apps have been designed for boaters, surfers, shellfish growers and anyone wanting to know where to run on the coast in the case of a tsunami.

Jan Newton, executive director and principal investigator at NANOOS, told me during a phone interview that the apps her team creates, the buoys they maintain and the data from those buoys would all disappear if Congress approves the president’s budget.

“I can tell you that based on the press in the Chronicle, we have reason to believe there is a risk,” said Newton.

NANOOS is funded through NOAA’s National Ocean Service. Trump’s budget proposal calls for cutting the National Ocean Service budget in half.

A phone voice message and email I sent to the National Ocean Service requesting comment went unanswered.

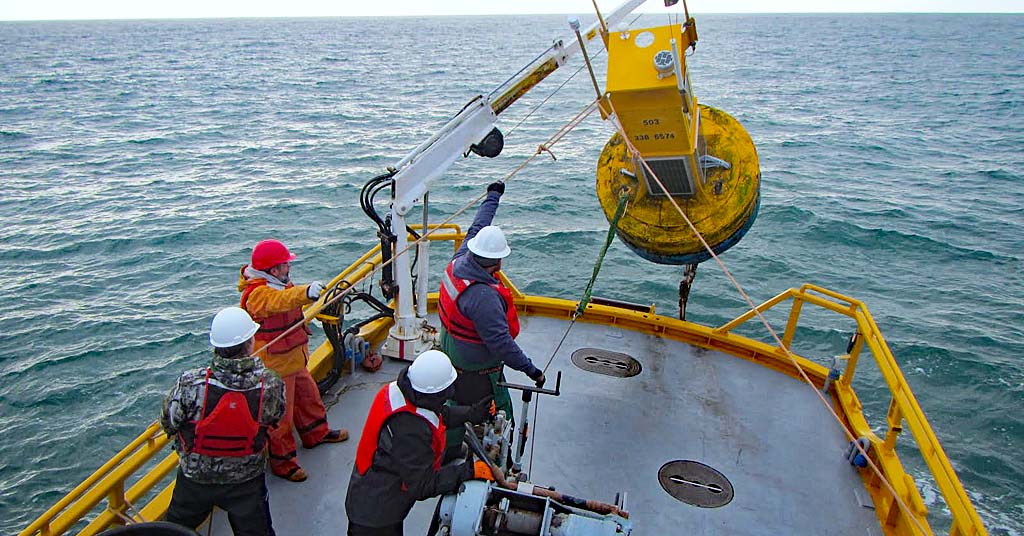

Program drop: Coastal Margin Observation and Prediction (CMOP) workers load a buoy near the mouth of the Columbia River. The ocean and estuary research program is dedicated to further understanding the linkage between the Columbia River and the Pacific Ocean. Photo: CMOP/CRITFC

Randy Henry, a recreational fisherman in Silverton, Ore., said the NANOOS NVS Fishers app has become his “go-to planning app” before heading out to sea.

Henry said without access to the NOAA data, the oceans will be less safe.

“My number one concern is safety,” said Henry. “If we lose the ability to access long ocean swell information and different weather conditions, we make it less safe, we’re going to see more fatalities.”

Henry, who in addition to being a recreational fisherman is also a board member of the nonprofit group Oregon Coalition for Educating ANglers or OCEAN. OCEAN worked with NANOOS to help put their apps into the hands of fishers along the Oregon and Washington coast.

Crossing the Bar, tribal involvement

The Columbia River mouth section of the NANOOS network is the Coastal Monitoring and Ocean Prediction (CMOP) program, operated by the Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fish Commission. This tribal organization took over operations from Oregon Health & Science University in 2020 as part of its efforts to research and gather information affecting salmon throughout their entire lifecycle.

CMOP conducts observations of ocean acidification, the salmon food web and enhanced predictions of changes to juvenile salmon habitat in estuary wetland.

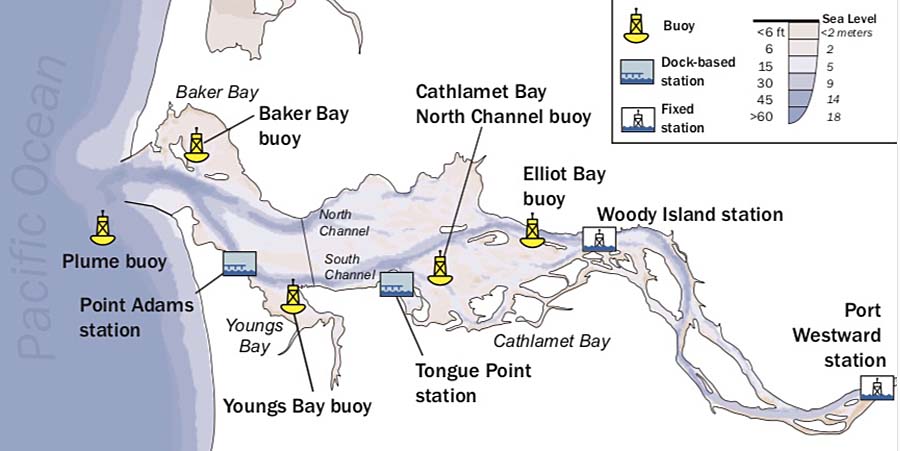

Coastal Margin Observation and Prediction program observation network in the Columbia River lower estuary and coastal ocean. Map: CMOP/CRITFC

CMOP data also informs ocean-estuary forecasts, which are used by commercial shippers, recreational boaters and commercial and recreational fishers. The data is especially critical for Columbia River Bar pilots navigating the most hazardous river crossing in the United States at the mouth of the river.

“By supporting funding for … CMOP, we can ensure that the U.S. maintains the ocean intelligence necessary to protect our coasts, sustain our fisheries, inform our industries and preserve our fishing heritage for generations to come,” according to a Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fish Commission publication. “The Columbia River’s connection to the Pacific Ocean mirrors the connection between regional monitoring efforts and national well-being—each part strengthening the whole when properly supported.”

Crabs and Cooperative Institutes

Crystal Adams, executive director of the Oregon Dungeness Crab Commission, said fishers she works with use the NANOOS apps. Adams said she’s also concerned if NOAA data tracking ocean conditions disappears.

Adams said she agrees with the need to make government more efficient but disagrees with how the current administration is going about it.

“It’s important for these people to have this science,” said Adams. “And maybe not everything that [federal funding] pays for is good, but certainly a lot of it is. An all-out just-stop-doing-it is definitely not the right idea.”

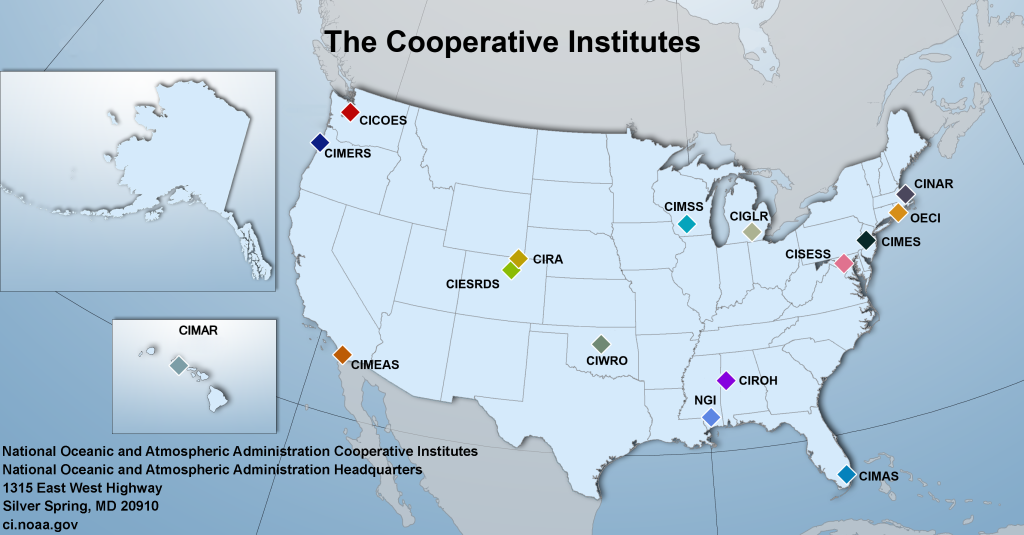

Cooperative Institutes in part provide the scientific basis for national policy decisions in areas such as climate change, disaster reduction, air quality, non-indigenous species and stratospheric ozone depletion. Map: NOAA

Adams said in addition to using the NANOOS apps, her commission has worked directly with NOAA-funded researchers to help monitor the health of the Dungeness crab fishery. This has included working with the Cooperative Institute for Marine Ecosystem and Resources Studies, or CIMERS, at Oregon State University.

CIMERS measures the health of the ocean. Adams said her organization had hoped to use research from the program to help get the Oregon Dungeness crab fishery certified as sustainable by the Marine Stewardship Council. MSC-certified fisheries frequently sell their products for more money than non-certified fisheries due to consumer demand for sustainable seafood.

The proposed budget calls for eliminating funding for NOAA’s Cooperative Institutes, including CIMERS at Oregon State University.

In a phone interview, Francis Chan, associate professor at Oregon State University and director of CIMERS, defended NOAA’s Cooperative Institutes (academic and nonprofit institutions that conduct research in support of NOAA goals).

“We believe that Cooperative Institutes help NOAA be even more responsive to the needs of people on the coast working in our waters, because we are right there with them,” said Chan. “I think the Dungeness Crab Commission is a perfect example of what opportunities we have and what opportunities we might leave off the table if we lose the Cooperative Institutes.”

Francis Chan. Photo: OSU

While possible cuts to NOAA programs might seem far away, some worry that current funding and staffing issues are already impacting NOAA’s role in overseeing the nation’s fish stocks.

Merrick Burden, executive director of the Pacific Fishery Management Council, said he’s concerned NOAA surveys of some West Coast fisheries might not occur this summer due to staffing and funding issues, which means fewer fish will be caught.

PFMC is one of eight fishery management councils that create management plans for fisheries designed to prevent overfishing. PFMC oversees fisheries in Oregon, Washington, California and Idaho.

Fishery councils base their management plans on fish population studies called stock assessments. These are based largely on data collected by NOAA’s ocean-going science vessels.

If NOAA vessels are under-staffed and can’t perform their stock surveys, this can create gaps in a fishery stock’s data record. In the absence of a complete data record, Burden said his organization is required to “give more deference to conservation.”

“And so that starts to reduce the allowable catch limits that we can provide for fishermen,” said Burden. “It shortens the fishing time, it shortens the fishing volume and it can be disruptive in an economic sense.”

Concerns about adequate stock surveys are shared by others, including a member of the New England Fishery Management Council and Alaska Senator Dan Sullivan. The Republican senator is quoted in National Fisherman as saying, “I hope to hell someone from NOAA is watching—get on with the surveys, goddamn it. You can tell I am rattled about this.”

In response to an email requesting comment, James Miller, NOAA Fisheries public affairs officer, responded: “Per long-standing practice, we are not discussing internal personnel and management matters, nor do we do speculative interviews.”

President Trump’s budget provides $789.327 million for the National Marine Fisheries Service, a reduction of $324.470 million.

Killing Sea Grant

Other ocean monitoring efforts on the chopping block include the Sea Grant colleges.

There are 34 Sea Grants housed at universities nationwide. Sea Grants were created to mirror land-grant colleges and their “extension” efforts to provide scientific support for farmers, ranchers and other agricultural producers. Instead of providing scientific know-how for producers on land, the Sea Grants aid producers who make their living from the ocean, or in some way from bodies of water. Sea Grants also aid coastal communities more generally as well as fund original scientific research.

The White House budget proposal calls for eliminating all funding for the Sea Grant program.

The termination letter looked “like it was written by AI or an intern that took 10 minutes to review our website.”

In the summer 2011, straight out of journalism school, I received a communications fellowship from Oregon Sea Grant (OSG) housed at Oregon State University. My job was to write stories that promoted the organization’s science and outreach, something I continued to do on and off for the agency for another three years.

To give you a sense of the applied science Sea Grants do, consider just a handful of the Oregon Sea Grant projects I wrote stories about.

Stories included how OSG helped set up an albacore tuna canning operation on the Oregon coast that used the latest canning methods (I can still find this tuna in the store); how OSG-funded scientists worked directly with the Oregon Dungeness Crab Commission; how OSG helped coastal communities prepare for a Cascadia Subduction Zone earthquake; and how OSG-funded science helped a small Oregon oyster hatchery respond to ocean acidification.

Oregon Sea Grant declined to comment for this story. The program’s homepage links to a form letter supporting the Sea Grant program addressed to Oregon’s congressional delegation. The letter highlights the program’s applied research.

Washington Sea Grant didn’t return my messages requesting comment.

In an April 14 blog posted on her program’s website, Terrie Klinger, interim faculty director for Washington Sea Grant, suggested that panic over funding wasn’t yet warranted.

“At this time, the [Trump] Administration’s proposal is only that: a proposal,” wrote Klinger. “The ultimate results of the Congressional budget process remain to be seen.”

Klinger’s letter went on to tout the economic importance of the Sea Grant program, noting that: “WSG’s work in 2018-2023 brought more than $190 million in services and economic benefits to the state—an impressive return on the federal funds invested in the program and a clear indication of the tangible effects on real lives and livelihoods.”

In an email responding to my request for comment on the potential end of the Sea Grant program, Monica Allen, director of public affairs at NOAA Research, wrote: “It’s NOAA’s longstanding practice not to discuss internal management and personnel matters, and we don’t speculate about things that may or may not happen in the future.”

Defunding climate adaptation

In addition to working for Oregon Sea Grant, from April 2014 to August 2020 I worked as a science communicator for the Pacific Northwest Climate Impacts Research Consortium, or CIRC. CIRC was housed at Oregon State University at the Oregon Climate Change Research Institute.

CIRC was funded through a competitive NOAA grant designed to help communities respond to climate change impacts, including drought and wildfire. Called the Regional Integrated Sciences and Assessment Program, the competitive grant was later renamed the Climate Adaptation Partnerships Program, or CAP.

Among its many projects, CIRC did original climate change research that led to multiple scientific publications, as well as a large dataset that was used to create a suite of free, online “climate tools” that allowed users to look at historical and projected climate data for their regions.

The tools were used by community members in Spokane, Wash. to create a climate change adaptation plan. Hydrologists funded through CIRC helped water managers in Portland and Seattle create better predictive models of their water supplies.

Sources contacted for this story referred to a “climate of fear” surrounding public comment about government programs.

After I left OSU, the NOAA CAP grant was awarded to the University of Washington, which named its group the Northwest Climate Resilience Collaborative.

On May 5, Timothy Carrigan, the acting director of NOAA’s Grants Management Division sent a letter to Northwest Climate Resilience Collaborative members at the University of Washington informing them that their CAP grant was being terminated as an effort to “streamline and reduce the cost and size of the Federal Government” and because the collaborative no longer complied with “program goals or agency priorities.”

Jason Vogel, former co-director of NCRC at the University of Washington, calls the assertion that he and his colleagues were no longer in compliance with CAP’s goals and priorities “pretty vague” and “demonstrably false.”

“It looks like it was either written by AI or an intern that took 10 minutes or less to review our website,” said Vogel of the termination letter. “Providing a termination notice that’s effective immediately without allowing for the adequate time to wrap up the work that you’re doing causes a tremendous amount of harm, not just to the people that are employed, but to the communities that we’re working with.”

NCRC projects included working with Tribes along the coasts of Oregon and Washington to prepare for climate-related coastal hazards. NCRC also worked with community members in rural Umatilla and Morrow counties in northeast Oregon, to address water scarcity and contaminated drinking water issues.

The CAP program is housed under NOAA’s Office of Oceanic and Atmospheric Research (OAR).

Trump’s budget proposal calls for the elimination of OAR as a NOAA line office, or sub-agency.

Along with the CAP program, OAR also houses the Sea Grant program and NOAA’s Climate Program Office.

NOAA’s OAR communications office did not provide responses to my email questions related to the termination of NCRC’s grant and the proposed elimination of OAR.

“Climate of fear”

In response to multiple queries regarding this story, NOAA officials provided only generic official comments.

This might be the result of what several sources contacted for this story referred to as a “climate of fear” surrounding public comment about government programs.

Time and again, people and organizations receiving NOAA funds either turned down interview requests for this story or simply chose not to respond to emails and voice messages.

Beyond the handful of individuals quoted in this story, most sources agreed to talk only on background.

Is this silence justified? I don’t know. But I suspect being unwilling to talk publicly won’t help publicly funded science.

As journalist Michael Lewis and his coauthors point out in their book Who Is Government? The Untold Story of Public Service, while Americans tend to have strong opinions about the federal government most of us really have no idea what the federal government does.

I suspect that NOAA and many other government programs are a lot like vaccines: they’re a potential victim of their own success. They manage collective risk and do it so well that we won’t know how much we need them until they go away.

The views expressed in this article belong solely to its authors and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of anyone else associated with Columbia Insight.