The Blue Mountains serve critical environmental functions. It’s time to create a vision that responds to the many threats the area faces

Kind of a big deal: Oregon’s Blue Mountains, seen here from Chesnimnus Vista looking at the Wallowa Mountains, occupy almost a sixth of the state’s land area. Photo: Dave Jensen

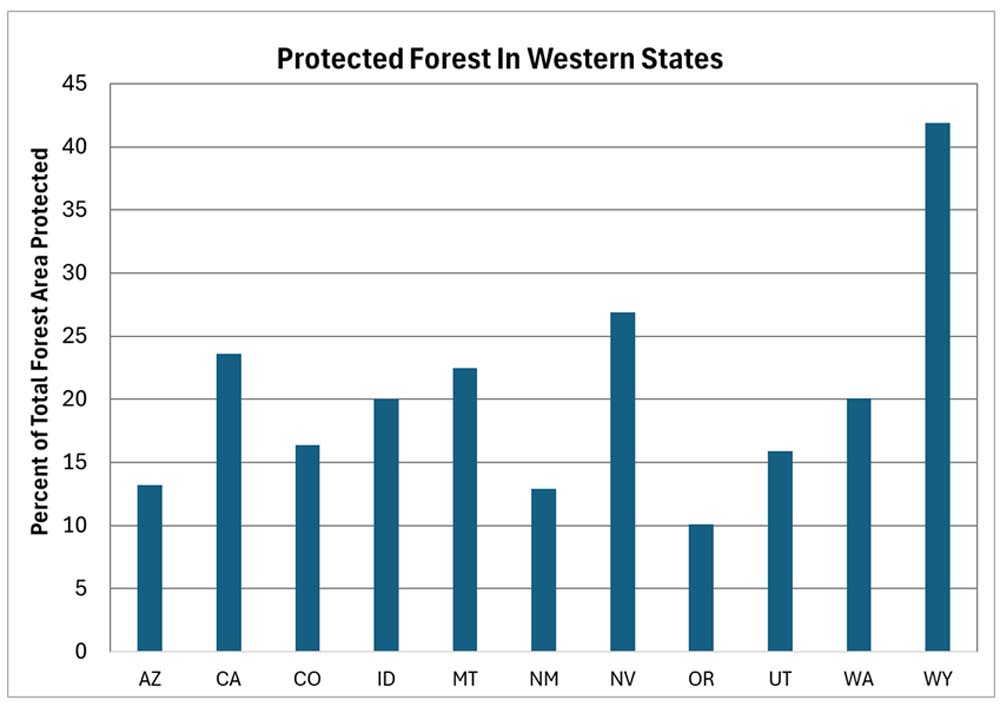

By David Mildrexler and Beverly Law. May 8, 2025. Oregon has more forest area than any state in the contiguous western United States. Yet it’s also the western state with the lowest proportion of its forests protected at the highest conservation levels, such as wilderness areas or national monuments.

Less than 10% of Oregon forestlands have strong protections, yet its mature and old forests have some of the highest carbon densities in the world and an exceptional diversity of forest types and habitats. This is an extremely small percentage of protected forest and not enough to minimize losses of animals and plants due to climate change.

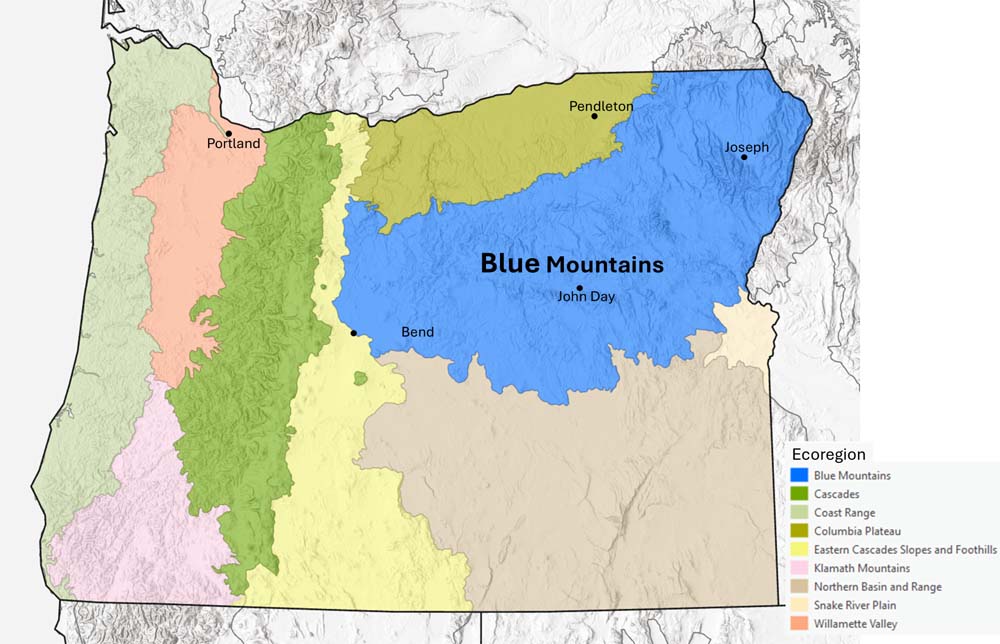

About half of Oregon’s forests are east of the Cascades Range crest. Of this “eastside” forest, the majority falls within Oregon’s largest ecoregion, the Blue Mountains.

The Blue Mountains consist of a series of majestic ranges interspersed with remote valleys, rugged canyons carved by free-flowing rivers and expansive forests and grasslands.

In the Blue Mountains you’ll find Oregon’s largest federally designated Wilderness Area (Eagle Cap Wilderness), North America’s deepest canyon (Hells Canyon), the largest intact Pacific Northwest grassland (Zumwalt Prairie Preserve) and one of the longest free-flowing rivers in the western United States (John Day River).

Oregon’s largest ecoregion, the Blue Mountains stretch into parts of Idaho and Washington. Map: David Mildrexler

This complex and diverse landscape spans over 27,000 square miles, an area larger than West Virginia. The Blue Mountains stretch beyond northeastern Oregon’s borders to the Rocky Mountains of central Idaho, and north into southeastern Washington.

The Blue Mountains are hydrologically critical. They function as water towers, accumulating snowpack that supports the headwaters of many of eastern Oregon’s streams and rivers, including some that flow into the Columbia Plateau and Great Basin ecoregions.

Few places in America this large remain intact with the opportunity to protect vital habitats that support the movements of large mammals, migratory fish and birds—elk, moose, sockeye salmon, golden eagles—and also provide clean water, climate benefits, outdoor recreation and jobs.

Key connector

The Blue Mountains run 300 miles from the eastern flank of the Cascade Range to the western edge of the Rocky Mountains.

The east-west orientation of the Blue Mountains forms a natural transverse linkage between the Cascades and Rockies, providing connectivity across systems that are otherwise characterized by north-south directionality.

The Blue Mountains have thus traditionally provided support for broad-scale species movement between these major mountain chains in response to climatic change.

The Blue Mountains consist of numerous mountain ranges that together form an east-west bridge linking the Cascades to the Rocky Mountains. Graphic: David Mildrexler

In a rapidly warming climate, safeguarding connectivity across the Blue Mountains becomes even more important.

To effectively move across the landscape, species need protected and connected habitats.

Due to human impact—roads, logging, mining, agriculture, transmission lines—the Blue Mountains now lack such a true, unified network.

Protected areas are separated by large distances. Dense, road networks crowd much of the area between them.

Alone, none of the ecoregion’s individual wilderness areas are large enough to support the home ranges, genetic diversity and populations of wide-ranging species like bighorn sheep and wolverine.

But it’s not only wildlife that require migration corridors.

Plants also need a large, connected landscape to move and adapt to a warming world, particularly northward and upslope to cooler climates.

The Blue Mountains need an ecoregion-wide system of reserves and corridors where species are free to live, move and adapt to a changing climate.

Crossroads

The Blue Mountains may be of exceptional conservation value, but the future integrity of the area is uncertain.

In addition to persistent logging threats, roads built for resource extraction (largely between the 1920s and 1980s) have left a legacy of fragmentation and degraded watersheds. Enough roads have been built in the national forests of the Blue Mountains to circle the globe.

The remaining roadless areas are of importance to the region’s ecology and culture, yet they continue to be impacted by logging, road-building and motorized recreation.

Oregon has more forest area than any state in the western U.S., but the lowest proportion of its forests with strong protections. Data from Law et al. 2021. Graph: David Mildrexler

No new wilderness areas have been designated on national forest lands within the Blue Mountains since 1984, even though the importance of safeguarding roadless areas has been well established for decades.

“Because roads crisscross so many forested areas on the Eastside, existing roadless regions have enormous ecological value. Unfortunately, few of these remaining areas are protected,” according to a 1993 report authored by the Eastside Forests Scientific Society Panel and submitted to the U.S. Congress and President Bill Clinton. “Although roads were intended as innocuous corridors to ease the movement of humans and commodities across the landscape, they harm the water, soils, plants, and other animals in those, landscapes.”

More recently, the Forest Service proposed to weaken the region’s large-tree protection measure, the 21-inch Rule (which prohibits cutting most trees larger than 21 inches in diameter), setting the table for the Trump administration’s plan to log mature and old forests irrespective of their ecological and cultural values.

For now the rule remains in place, safeguarding about 3% of the largest trees in eastside forests.

These trees store over 42% of the total aboveground carbon in forests that are recovering from a century of logging that targeted old-growth trees.

Forest Plan revisions

The Forest Service is currently revising its 1990 Land and Resource Management Plans for the Blue Mountains National Forests.

Three national forests are included in the revision: the Wallowa-Whitman, Umatilla and Malheur. Together these forests cover about 5.5 million acres, a substantial portion of national forest lands within the Blue Mountains.

As part of the revision process, six designated wilderness areas will be evaluated for expansion opportunities, along with new areas that include large blocks of roadless habitat.

In the revised plan, the USFS can recommend new areas for wilderness designation.

However, only Congress can officially designate areas as protected Wilderness.

In a 2022 paper published in Frontiers in Forests and Global Change, we identified the highest priority forestlands in Oregon for protecting biodiversity, mitigating climate change and safeguarding clean water. Strong protections that prohibit logging, road-building and mechanized recreation are crucial for these areas.

Overlap of these areas with wilderness-quality lands indicate places of exceptional conservation values vital to the future of the Blue Mountains, and our region’s efforts to fight climate change and safeguard biodiversity. Examples of key areas are:

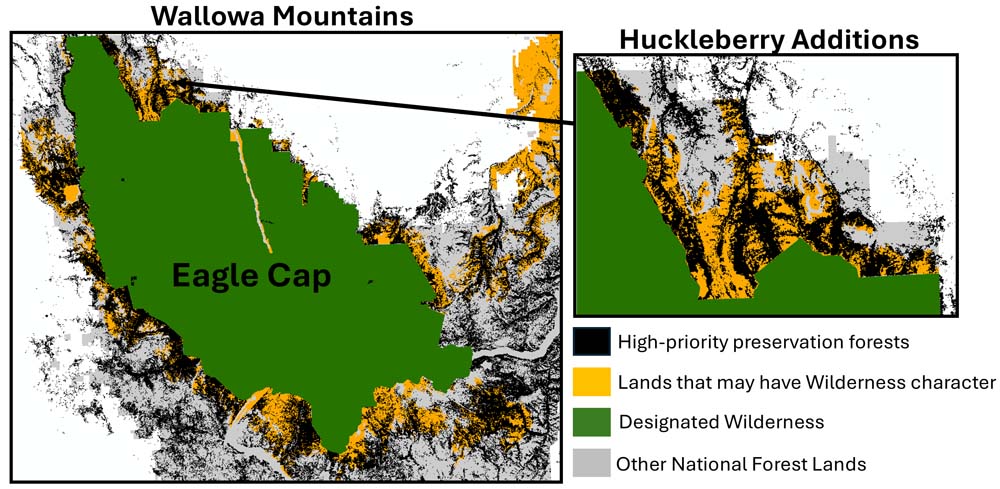

Wallowa Mountains

In northeastern Oregon, potential Eagle Cap Wilderness additions, such as the Huckleberry Mountain roadless area, contain vast areas of high-priority forests for protection of climate, biodiversity and water. Map: David Mildrexler

Large, potential wilderness additions adjacent to the Eagle Cap Wilderness harbor abundant, high-priority forests. The Huckleberry Mountain roadless area is a prime example of an Eagle Cap Wilderness addition.

These wilderness-quality lands span a long portion of Eagle Cap’s northern boundary.

Three trails traverse the roadless area to the wilderness, which is rich in old-growth forest and salmon-bearing streams.

It also links habitat and travel corridors for wildlife between the Eagle Cap Wilderness and the Minam River Wildlife Area. Adding the area to the Eagle Cap Wilderness would safeguard a strategic forest reserve and secure landscape connectivity.

The Lake Fork roadless area connects the Eagle Cap and Hells Canyon Wilderness Areas. This botanically diverse area is a mixing zone between the Wallowa Mountains and Hells Canyon, integrating high- and low-elevation plant communities. A protected Lake Fork Wilderness linking two of Oregon’s greatest wilderness areas would be a major step toward connecting the system, while safeguarding a large, contiguous area of high-priority forests.

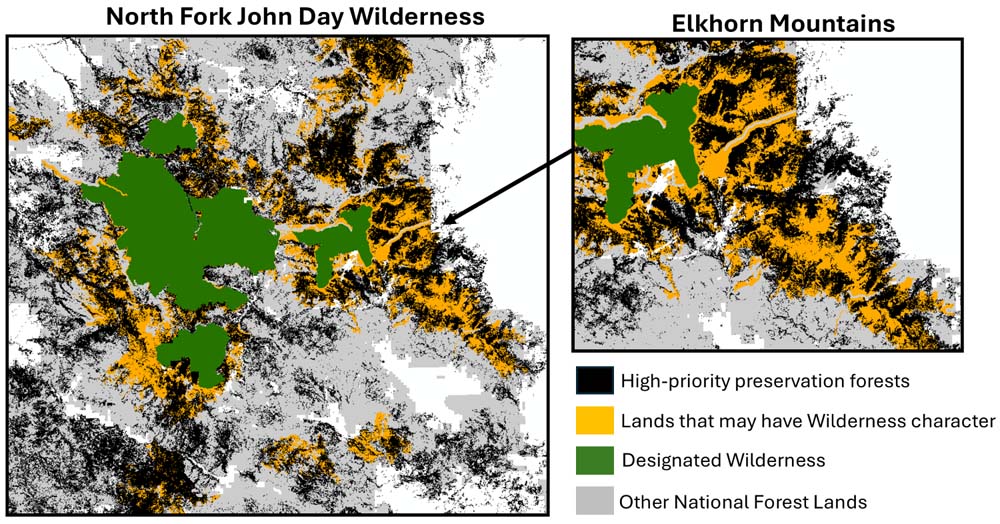

North Fork John Day Wilderness

In the North Fork John Day region, wilderness-quality lands like the Elkhorn Mountains are rich in high-priority preservation forests. Map: David Mildrexler

The forested, mountain landscape of the North Fork John Day Wilderness encompasses portions of the Elkhorn and Greenhorn Mountains, and holds the headwaters of the North Fork John Day River, the longest undammed river in Oregon.

Located in the heart of the Blue Mountains ecoregion, the Elkhorn Mountains’ high-elevation, moist, mixed-conifer forests provide species-rich habitat and clean, cold water that supports fisheries, agricultural lands and provides drinking water to communities.

Wilderness recommendation by the Forest Service would be an important step toward protecting this crucial forest and cold-water refugia.

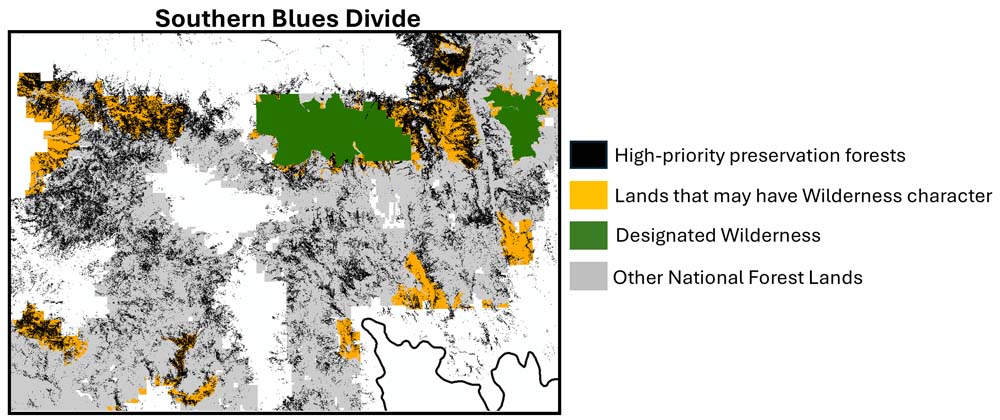

Southern Blues Divide

In the Southern Blues forest belt and wildlife corridor, wilderness-quality landscapes like Aldrich Mountain, McClellan Mountain and Glacier Mountain contain abundant, high-priority forests for protection. Map: David Mildrexler

The Southern Blues Divide is a forest-belt connector and wildlife corridor across the southern Blue Mountains. It includes the headwaters of the South Fork John Day River and numerous Great Basin rivers.

Several wilderness areas span its crest alongside large, roadless areas important for maintaining connectivity across this more fragmented part of the Blue Mountains.

The Trump plan

For decades, the Blue Mountains have been fragmented by road-building and management that threatens their functionality as a region-wide connector.

Without establishing new protections, we run the risk of losing our remaining high-quality, intact landscapes to more of the same logging, road building and mechanized recreation that we have so much of already.

Eventually we’ll have no system left to connect at all.

If we don’t take action to establish a system, over time, as climate change and human pressures worsen, the Blue Mountains will become increasingly fragmented into disjointed, isolated areas surrounded by a sea of degraded lands.

This is the path we are on with national forest lands.

Now the Trump administration wants to ramp up aggressive logging everywhere. It’s a self-fulfilling prophecy—degrade lands through management, then claim the wilderness quality is gone.

Ecological and financial sense

Large areas of wilderness-quality lands remain unprotected in the Blue Mountains.

These areas are strongholds for clean, cold water, fish and wildlife habitat, large and old trees and valuable ecosystem services.

Protecting these areas as part of a region-wide system of reserves and corridors is a major opportunity to secure resilience for the Blue Mountains while supporting connections between the Cascade Range and Rocky Mountains.

Intact landscapes don’t require costly restoration measures the way degraded lands do.

And they are among the most effective areas for addressing pressing problems, including habitat loss, water security and climate change, while maintaining hunting and gathering, fishing and recreation.

Protecting what’s left of our region’s intact forest landscapes is the most cost-effective management solution for these lands.

The Blue Mountains Forest Plan provides the opportunity to consider the landscape-scale functions of the Blue Mountains, and to recommend protection of key areas to help secure resilience and connectivity across this vital region.

The views expressed in this article belong solely to its authors and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of anyone else associated with Columbia Insight.

Native Oregonian David Mildrexler is a systems ecologist with Eastern Oregon Legacy Lands.

Beverly Law is professor emeritus of Global Change Biology, Terrestrial Systems Science at Oregon State University. She is a fellow of the American Geophysical Union and a Leopold Fellow.

Those that do not know their collective history get to do it again, as the article so well mentions, “one last time.”

The phrase ‘motorized recreation’ should be banned from use in any report, let alone those funded by the public and written by folks in otherwise good faith. It should be replaced by ‘willful mechanized destruction.’ Those folks believe that nothing is better than something, yes they are that stupid.

They are NOT out for recreation. They terrorize their own neighborhoods and make them unlivable, and simple go out into the larger environment to spread the damage. No other society tolerates or glorifies this conduct. It is terrorism, NOT recreation.

And, they don’t care. When I look at, or listen to Trump and/or his supporters, I realize that these are folks that CAN’T care.

It may be too late. Welcome to New Afghanistan! Enjoy your newfound recreation, cutting sandals out of tires, and your new diet of cornmeal mush and muffins, if corn will grow. If not, hey, grow poppies and go down that road – on foot.