Permitting for the Cascade Renewable Transmission Project has hit a snag. Developers say it’s a minor hitch

High-powered waterway: The Columbia River, seen here from Lyle, Wash., has long been industrialized. More is on the way. Photo: Chuck Thompson

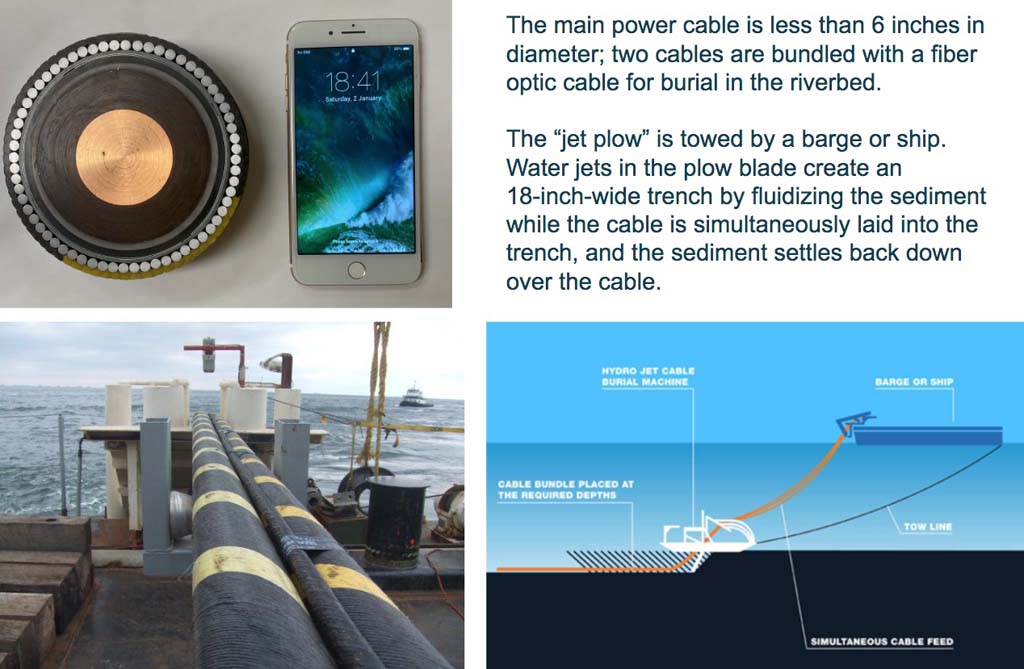

By John Harrison. March 27, 2025. Imagine a six-inch-thick, high-voltage electricity transmission line running underwater on the bottom of the Columbia River, from just east of The Dalles, Ore., to Portland. The line carries mostly wind and solar power from eastern Washington and Oregon, Idaho and Montana, the windiest, sunniest places in the Pacific Northwest.

Now ask yourself, really? Could it be done? Is it necessary?

The answer to each of these questions is yes, yes and depends on your perspective.

As wild as it seems, a (mostly) underwater power transmission line beneath the Columbia River could help lower overall electricity prices, preserve tens of thousands of acres from the visual despoilment of wind turbines and solar panels and provide a needed boost to the region’s electricity transmission supply.

Why do it? Because the Columbia River Basin doesn’t have the capacity to transmit the oncoming avalanche of electricity demand needed to power data centers and high-tech businesses, while also meeting carbon-free power requirements enshrined in law in Oregon and Washington.

To address the problem, a pair of companies proposed the underwater cable back in 2020. Called the Cascade Renewable Transmission Project, it promises to deliver renewable energy to densely developed areas west of the Cascade Range.

The companies making the proposal are Sun2o Partners, a renewable resource developer based in Connecticut and New York; and PowerBridge, a developer of high-voltage transmission based in Connecticut.

“The only places you can site solar and wind at scale are, for the most part, east of the Cascades. But the demand, the need for the electricity, is in Portland and Seattle, on the west side,” Corey Kupersmith, the New York-based renewable energy developer who cofounded Sun2o and dreamed up the cable scheme, told the Associated Press in 2021.

How it’ll be built

The Washington Energy Facilities Siting Council describes the Cascades Renewable Transmission Project as a 320,000-volt or 400,000-volt direct current cable or cables carrying roughly 1,100-megawatts of power.

The line would traverse Clark, Skamania and Klickitat counties in Washington before connecting with the existing Bonneville Power Administration Big Eddy, 500,000-volt alternating current substation located near The Dalles (the eastern Interconnection), and the existing Portland General Electric Harborton 230,000-volt alternating current substation located in Northwest Portland (the western Interconnection).

In all, the project would span about 100 miles.

Prysmian video illustrates how underwater cables are laid. Video: Prysmian/YouTube

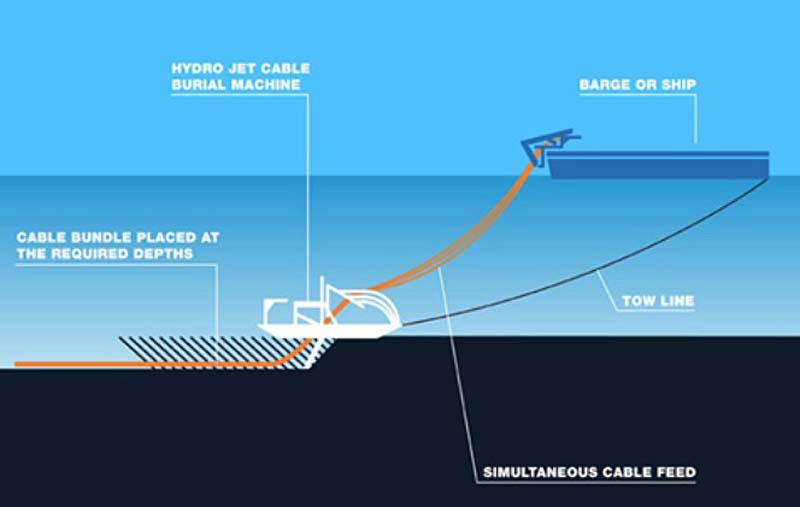

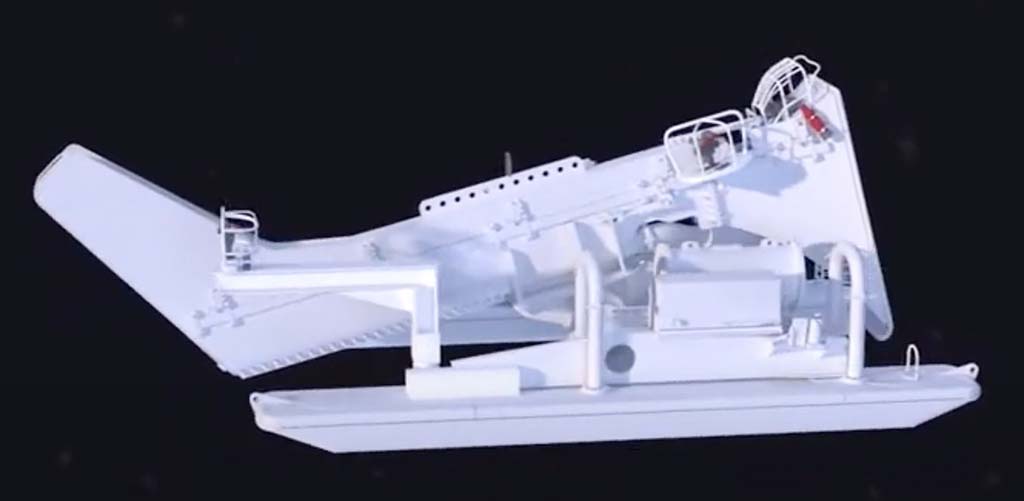

The majority of the line would be installed in the bed of the Columbia River using a Hydro Jet Cable Burial Machine, or “hydroplow.”

The hydroplow—built by the Milan, Italy-based company Prysmian—temporarily emulsifies or “fluidizes” sediment in an approximately 18-inch-wide trench, places the cable in a trench and allows the sediment to settle back over the cable.

In the Columbia River, the power cable would be buried at a depth of 10 feet (deeper in some places) in the riverbed.

Where the cable cannot be buried, a concrete mattress or a rock berm would be used to keep the cable weighted down and protected from damage.

An approximately 7.5-mile segment of the line would be buried in lands adjacent to the river near Stevenson, Wash., to avoid Bonneville Dam.

From the interconnections, the cables would also be buried underground in Oregon to the edge of the Columbia River on each end, and in the bed of the Columbia River in Oregon and Washington.

The visible structures, such as converter stations and short segments of overhead transmission, would be located in Oregon.

The overland component of the project in Washington would be located in public rights-of-way along Washington Highway 14, Ash Lake Road and Fort Cascades Drive.

Proponents of the project say environmental impacts would be short-term and outweighed by environmental gains, including reductions in air and water pollution from burning natural gas, petroleum fuels and coal in thermal power plants.

Environmental concerns

Not surprisingly, the idea of digging a trench through the bottom of the Columbia River, right down the middle of the Columbia River Gorge National Scenic Area, has created uneasiness about environmental impacts.

Opponents of the idea include environmental groups and the Confederated Tribes of the Warm Springs and the Confederated Tribes and Bands of the Yakama Nation, which have historic fishing rights in that stretch of the river.

Yakama Nation Rock Creek Band member Elaine Harvey sees the Cascade Renewable Transmission Project as yet another industrial enterprise that’s brought harm to her people.

As Harvey and Rock Creek Band Chief Bronsco Jim Jr. wrote in a Columbia Riverkeeper newsletter in 2021: “Ours is a living culture, and we are being cheated by progress—an unrelenting cultural extinction in the name of energy development.”

Cascade Renewable Transmission Project route map. Image: PowerBridge

Columbia Riverkeeper, itself, is taking a wait-and-see approach to the proposal.

“Columbia Riverkeeper is not yet opposed to the project, but there are many remaining questions with very little information,” Teryn Yazdani, Columbia Riverkeeper staff attorney, told Columbia Insight. “We have major concerns about the short-term and long-term environmental impacts of dredging a giant trench through the river and how it will affect aquatic species and water quality.

“We have a laundry list of concerns. Impacts to salmon and other aquatic species. Concerns about the 40- to 50-year lifespan of the project without any clarity around project decommissioning, maintenance and repairs, especially maintenance or repairs in sensitive areas for species. Concerns about how the project will be impacted by potential seismic events or vessel strikes.”

Yazdani and others have also raised questions about how water quality might be impaired from heat generated by the cable and how that would exacerbate existing heat pollution concerns in the river, which threaten salmon and other species that need cold water for survival.

“We are also very concerned about the precedent that this project would set for making the Columbia River a utility corridor, allowing anyone to drop a transmission line in the bottom of the river,” says Yazdani. “At this point, without more extensive, site-specific studies, it’s hard to be convinced that the impacts of this project would be minimal.”

Asked about some of these concerns, PowerBridge Senior Vice President and Chief Development Officer Chris Hocker told Columbia Insight that modeling shows that heat coming off of the cable will be “totally dissipated” by surrounding sediment by the time it hits the water column.

“The decommissioning choice would be up to the agencies, whether the cable should be removed or de-energized and simply left in place,” said Hocker. “The cable itself doesn’t require periodic inspections. You don’t have to go down and do anything with it.”

Permitting delays, project timeline

Filings for construction permits with the federal government, as well as Oregon and Washington state energy facility siting councils, had been expected toward the end of this month.

However, last week, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers said part of its required permit application had been withdrawn due to lack of information.

“USACE withdrew the Section 10 and Section 404 permit application for The Cascade Renewable Transmission Project on March 10, 2025,” USACE spokesperson Jeffrey Henon told Columbia Insight this week. “We requested additional information from the permit applicant but haven’t received a response from them. We cannot provide a timeline because further review is dependent on the applicant submitting this additional information. The Section 408 review is proceeding.”

Section 10 of the Rivers and Harbors Act of 1899 requires authorization from the Secretary of the Army, acting through the Corps of Engineers, for the construction of any structure in or over any navigable water of the United States.

Section 404 of the Clean Water Act requires authorization from the Secretary of the Army, acting through the Corps of Engineers, for the discharge of dredged or fill material into all waters of the United States, including wetlands.

How the Columbia River trench will be dug. Illustration: Prysmian

In an interview with Columbia Insight, PowerBridge’s Hocker brushed off the holdup, characterizing the delay as a simple administrative issue on the Corps’ end.

“It has no impact on our process going forward,” said Hocker. “We’re going to be completing the studies and providing the information. … The idea is to have the studies complete by the end of the second quarter [of 2025], at which point unless we have significantly changed the application, then basically the Corps picks up where we left off.”

The company also needs to have permits approved by both the states of Oregon and Washington. Hocker said that, “moving in parallel paths with Washington, Oregon and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers,” PowerBridge hopes to have all permitting complete by the end of 2027.

“From there would be a three- to four-year time period for construction, all of that driven by everything going on globally in this industry,” he said.

Hocker said the power line could be operational some time in 2030 or, more probably, 2031.

Company experience

Randall Hardy, administrator of the Bonneville Power Administration (the region’s largest electricity and high-voltage transmission provider) from October 1991 to September 1997, and now an energy consultant in Seattle, has been advising the project proponents for about four years.

“They have mapped the riverbed very precisely and have a good idea of the terrain,” said Hardy, referring to Sun2o Partners and PowerBridge. “They have situated the line to avoid most if not all environmental issues, such as avoiding mussel beds, and spawning areas for salmon that spawn in or near the shoreline.

“They have been working with the Corps of Engineers to locate as close to the center of the river as possible, and they have been sensitive to protect indigenous cultural sites, which are mostly along the shoreline.”

Slide from a PowerBridge presentation on the Cascade Renewable Transmission Project. Image: PowerBridge

PowerBridge has been involved in the construction of underwater, high-voltage cables that carry power from New Jersey to New York, one from the Hudson River beneath New York Harbor and terminating in Manhattan, the other from New Jersey’s Raritan River to the south shore of Long Island.

PowerBridge’s Hocker said that while the technology that will be used in the Columbia River “is very well established,” the company has identified unique aspects of the Cascades Renewable Transmission Project.

“There’s an aspect of this project that requires coming out of the river to bypass the Bonneville Dam then going back into the river. We didn’t have to do anything like that for our projects [on the East Coast],” he says. “And in the Columbia River there is, of course, a lot of attention due to the impact on salmon and other resources. So, we expect that our project here will be much more heavily scrutinized.”

Tradeoffs

The proposed power line would carry about 1,100 megawatts, enough to power approximately 780,000 homes if all of it were dedicated to residential use, which it would not be.

Hardy says the alternative is an aboveground line or lines, which would rise about 100 feet above the ground and be strung between equally tall steel towers. That alternative would likely be more expensive and difficult to construct.

The “hydroplow” uses high-pressure water jets to emulsify riverbed materials, allowing for the passage of a “stinger” that allows cable from a surface vessel to be laid into an 18-inch-wide trench. Illustration: Prysmian

“You know how controversial siting transmission lines can be and, importantly, they can get the underwater cable done by 2030, at least five years sooner than building above ground,” said Hardy, adding that the underwater project would likely come with far less litigation.

“Often the answer we give is, compared to what?” said Hocker, when asked about opposition to the project. “Compared to not having renewable energy, and repealing the legislation in Oregon and Washington? Compared to offshore wind or overland transmission lines? Some sort of tradeoffs may be necessary. We think this is the least impactful way of getting the states to where they want to go.”

“The bottom line is that new transmission is needed to meet Bonneville’s queue for new transmission service,” said Hardy. “This is a really viable project that is needed to bring east-of-the-Cascades renewables to the west side where it is strongly needed.”

Waiting list for power

According to a November 2024 analysis by the Northwest Power and Conservation Council, the region’s energy planners are grappling with bottlenecks in key areas like Portland-Hillsboro and Puget Sound.

Expanding the transmission system to accommodate new energy development would require lengthy planning and construction times—sometimes spanning a decade or more.

The Bonneville Power Administration faces a growing high-voltage transmission dilemma.

The federal agency owns about 15,000 miles of high-voltage transmission in the Pacific Northwest, accounting for about 80% of the regional total. For scale, the Western Interconnection, which covers 11 western states, the Canadian provinces of British Columbia and Alberta and part of Baja California, Mexico, includes roughly 136,000 miles of transmission.

Prospective energy developers send Bonneville requests to hook up to their transmission system queue.

This queue has grown substantially in recent years. The agency reports having 272 projects capable of transmitting some 186,000 megawatts eligible for an upcoming transmission study, although many requests will be speculative and only a portion of these projects will ultimately reach construction, according to the Council.

Longtime energy reporter John Harrison had been at work on this story when he passed away in February. Work on his final story was completed by Columbia Insight staff. —Editor

I think it is interesting that we are focused exclusively on the at-site benefits and detriments of the project. We should be opposing the use of NW power to feed Amazon data centers that store customer cloud marketing data, as well as we should oppose the use of data centers to store personal cell phone data, and other frivolous personal uses. Large energy demand data centers should be reserved only for strategic national interests or scientific research.

Does this project contemplate removal of the aged and unsightly above ground transmission lines? Removal of these lines would greatly restore the beauty of the Gorge and potentially mitigate wildfire risks.