A partnership of conservation groups and private landowners is keeping logging in, but commercial development out

Green investing: Huge parcels of forestland in southwest Washington were liquidated in 2021. Now, new plans for the land are coming into view. Photo: Columbia Land Trust

By Kendra Chamberlain. February 19, 2025. Back in 2021, the SDS Lumber and Timber Company’s sale of its extensive mill properties and nearly 100,000 acres of Pacific Northwest forest reserves to sent a shockwave through the Columbia River Gorge as well as the global timber industry.

Now, through a complex partnership agreement, nearly all of the forests formerly owned by SDS in southwestern Washington are remaining open to logging, while being protected against future commercial or residential development.

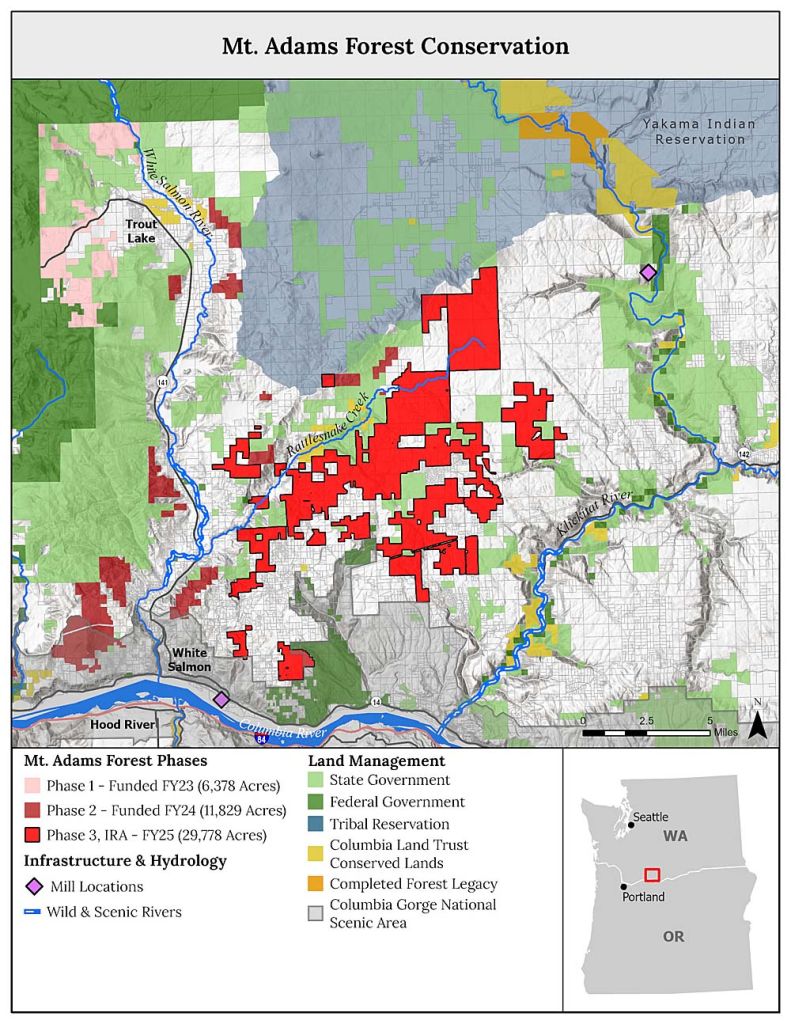

The Columbia Land Trust has announced a $36 million award from the U.S. Forest Service that will go toward establishing a new conservation easement on a 29,000-acre piece of former SDS Lumber land. (The award, which will flow through Washington’s Department of Natural Resources, came in mid-December and has not been impacted by recent freezes on federal grants, according to the Columbia Land Trust.)

The land is located in Washington’s White Salmon and Klickitat River watersheds.

The award is part of the Forest Service’s Forest Legacy program, which seeks to conserve timberland as open spaces and working forests, while maintaining wildlife habitat and clean drinking water.

Keeping timberlands as “working forests,” rather than carving up the land into commercial or residential parcels, is considered a major conservation win, according to Columbia Land Trust Executive Director Meg Rutledge.

“Working forests” is a malleable term that broadly refers to forestland that’s commercially logged, while sometimes also being managed to preserve certain areas for wildlife habitat and recreation.

“This entire region is under significant pressure of land conversion,” Rutledge told Columbia Insight. “There’s so much growth, and it’s not always strategic, when these large forestry blocks go up for sale, they can end up getting really fragmented.”

Phase Three of the management plan for former SDS Timber land more than doubles the size of protected area. Map: Columbia Land Trust

The deal is the third phase of a conservation strategy developed by the Columbia Land Trust, along with the landowner Twin Creeks Timber/Green Diamond Resource Company, The Conservation Fund and Washington’s Department of Natural Resources.

All told, the group has established conservation easements to cover 48,000 acres of timberland between the Columbia River and Mt. Adams. The easements contain restrictions on development aside from logging.

All of that land will be managed as working forest, but will offer public and recreational access, which Rutledge said was an important piece of the easement deals.

“Part of our motivation for this project was to conserve the land itself, as well as the values of how that land was being used,” said Rutledge. “So that does mean it will remain a working forest, which means they are part of both the rural economy as well as the forestry system economy.

“And it will continue to provide recreational access. That was a clear goal of this partnership, that these easements would ensure that recreational access was continued in these forests.”

Striving for balance

In 2021, Columbia Insight reported extensively on the sale of land owned by Bingen, Wash.-based SDS Lumber. The company’s 96,000-plus acres of commercial forest had been managed for decades under a 60-year harvest rotation, meaning the trees planted were allowed to grow for much longer than most other logging forests in Washington before being cut down.

At the time, The Conservation Fund stepped in to acquire 35,000 acres of the SDS timberlands, representing about a third of the land up for sale and including important oak habitat, river frontage and municipal drinking water sources.

That deal also included logging on the land, with prioritizations for protecting water quality and wildlife habitat.

Development curtailed: Houses out, hikers in. Photo: Columbia Land Trust

Twin Creeks Timber, owned by Green Diamond Resource Company, acquired 61,000 acres of land that it promised to manage as timberlands. Now, roughly 48,000 acres of that land, representing 79% of what Green Diamond acquired from SDS Lumber, is under various conservation easement agreements with Washington DNR.

That means that of the 96,000 acres of SDS Lumber land, some 83,000 acres are working forests under some form of protection from other development.

Jason Callahan, policy and communications manager at Green Diamond, told Columbia Insight that the forests will still be logged at rates “consistent with our management objectives for the land.”

“There are no limitations to what we do to manage our forest [under the easement],” Callahan told Columbia Insight. “But the conservation value is that intact forest has more conservation value than twenty-, thirty-, forty-acre ranchettes that are torn up and chopped up into little development spots.”

Callahan added that the company is certified under the Sustainable Forestry Initiative in the Columbia River Gorge.

“Green Diamond is committed to being a sustainable forest company, and we show that by that third party certification,” he said. “There’s a lot of work and money to do it, but, but it’s in line with the company values.”

Logging forests isn’t typically considered “conservation,” but groups like The Conservation Fund and Columbia Land Trust seem confident that a big tract of working forest is better for wildlife and watershed health than what other development might look like.

“This is an unusual partnership for several large conservation NGOs like The Conservation Fund and Columbia Land Trust to partner with industry groups, including Green Diamond, as well as investors,” said Rutledge. “I also think it’s what it takes to achieve conservation on such a large scale. It’s complicated, it’s ambitious, it’s rare.”

I am worried that the lessons of the past haven’t been fully learned. I was a student taking an Ecology class in college. I was completely blessed to have the class team-taught by two professors who earned their PhDs by being pioneers in controlled cutting and burning in the California Sierras and the wonderful lessons they taught me: the only way a forest that is being logged to be sustainable is to leave the trees you cut down in that forest to decay naturally, or the health of the soil will decline with each tree you haul away with its nutrients. That is a huge problem with allowing loggers to sell lumber, which I don’t see is being addressed here.

Well, as a forester that studied forestry in that region of Washington state I can assure you that soils are not an issue. Certainly in places like the sierra’s they are but not on the Washington coast. Generally speaking the Washington coast has 15 feet silty loam.

Logging forests isn’t typically considered “conservation,”

That’s because logging is not conservatives. It’s the opposite.

Maybe It’s better than developing the land, but it isn’t conservation.

I am optimistic. Acknowledgement of oldest old growth is the critical, telling, part of the whole “work & services” dynamic, and there is no mention in this story, of breaking that, when “allowing” logging. Commercial, wildfire prevention and natural systems restoration logging, done with experts'”best management practices” – for the whole forest – first – is the most important and necessary part. Corporations, after that, can keep running, as long as no one is taking pieces out of the natural cycle, as “business efficiencies”. As my father said, at our table, “take some, leave some”.