Adjacent to Eagle Cap Wilderness, nearly half of the Forest Service’s massive Morgan Nesbit project lies within the National Recreation Area

Shaky standing: Near Big Sheep Creek within the Morgan Nesbit Forest Resiliency Plan area, the Grossman Stand of ponderosa pine (foreground) and younger trees has been identified by the USFS as a place at risk of losing large, mature trees to fire. Photo: USFS

By Jordan Rane. January 16, 2025. As far as names go, Morgan Nesbit sounds pretty benign. The U.S. Forest Service’s Morgan Nesbit Forest Resiliency Project, however, has sown plenty of discord.

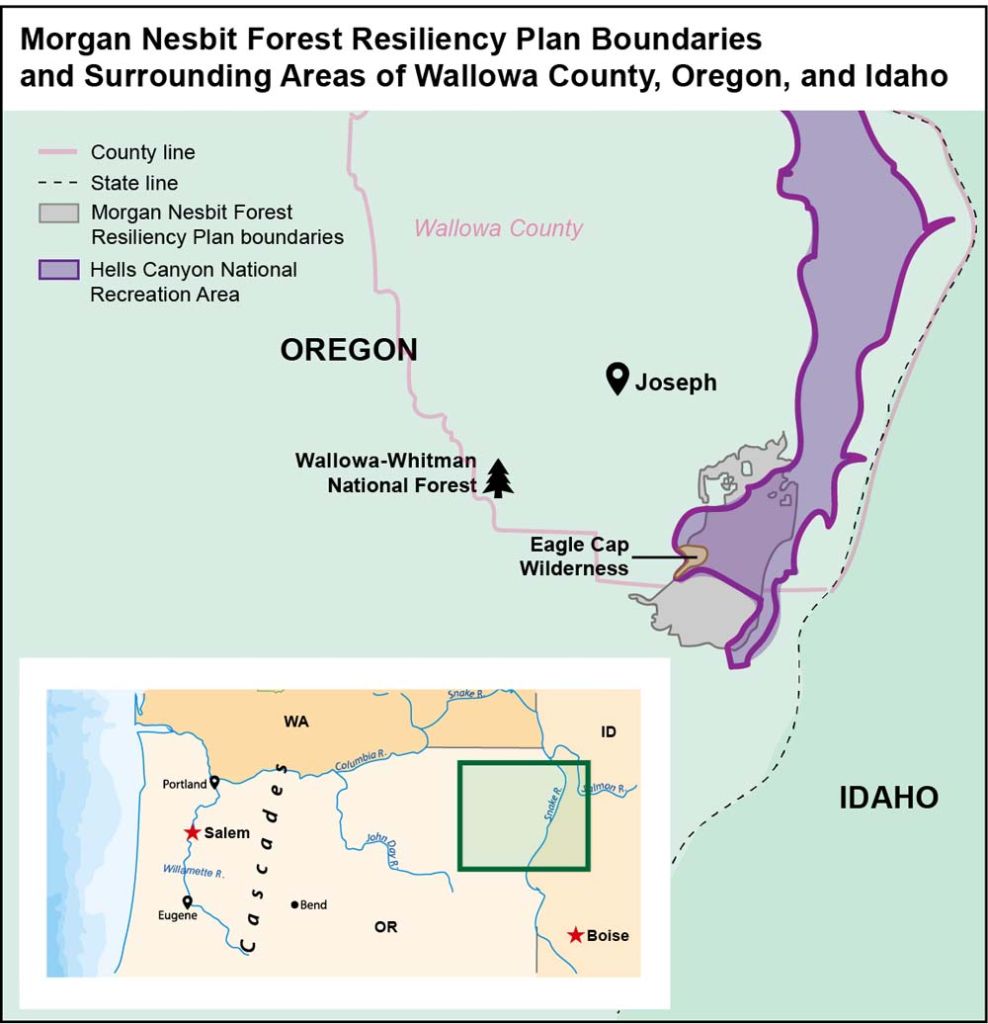

The forest management plan takes in a pair of remote mounds (Morgan Butte and Nesbit Butte) 20 miles southeast of Joseph, Ore., in northeastern Oregon’s Wallowa County, home to the treasured Eagle Cap Wilderness and Hells Canyon National Recreation Area.

The management project initiated by the USFS in 2020 across an 86,500-acre area targets a vast expanse of rugged canyonlands, river valleys and forested peaks in the Wallowa-Whitman National Forest.

The agency wrapped its second public comment period for the project late last month after the release of a Draft Environmental Assessment.

This follows five years of research, pre-scoping, story-mapping and scientific reporting on the region—including a wildlife evaluation with its own 20-page index.

Targeting one of the most prized outdoor recreation areas in the state, including thousands of acres inside Hells Canyon, the Morgan Nesbit Forest Resiliency Project has been on a long journey that appears to be nearing its conclusion.

Map: Mackenzie Miller

The plan’s latest phase may be its most exhaustive and challenging.

“There’s definitely a list of things about Morgan Nesbit that we’re not pleased with,” says Jamie Dawson, conservation director of Greater Hells Canyon Council, an organization dedicated to preserving Hells Canyon National Recreation Area, where about 45% of the project would be based.

Topping Dawson’s list is the project’s location, size and timber harvest.

“Would I have ever picked the crown jewel of the Forest Service system in the Northwest and probably the entire country for a substantial part of a nearly 90,000-acre logging project? Probably not,” says Dawson, who adds that “resiliency project” is often used as a euphemism for, among other things, cutting down trees.

“The history of logging in Oregon has always been a series of rebranding efforts to see what is the most palatable phrase for them to still be able to meet their timber targets,” says Dawson. “Words like ‘resiliency’ can be attached to anything from a terrible logging campaign that we really dislike to something like Morgan Nesbit that’s just super-complex and needs to be treated as such.

“So, while the Forest Service has a mandate to produce a certain amount of timber every year, it’s critical that it’s not treating Hells Canyon—this incredible, congressionally protected landscape that’s been included in the equation—just like some regular-old acre that’s another part of the timber base. Our primary concern is that they’re not flattening the whole project area into a one-size-fits-all prescription—and that’s a lot of what we’ve seen in this draft [environmental assessment].”

“Resiliency” or “logging”?

The Morgan Nesbit Forest Resiliency Project boundaries are adjacent to the Eagle Cap Wilderness, one of America’s most majestic alp-scapes.

“None of Morgan Nesbit is in the Eagle Cap Wilderness, which is a congressionally designated wilderness area where we wouldn’t propose projects like this,” says USFS District Ranger Brian Anderson, who heads the Morgan Nesbit project for the Hells Canyon National Recreation Area and Wallowa-Whitman National Forest.

As for Hells Canyon, and thousands of additional acres in Wallowa-Whitman National Forest, “that’s an area ranked as high-risk for wildfire hazard as well as insect and disease outbreak where we felt there was a real need for some active management,” says Anderson.

Beauty adjacent: The Morgan Nesbit plan borders, but doesn’t infringe upon, Oregon’s beloved Eagle Cap Wilderness. Photo: Joseph COC

Other critical needs the project targets, according to the Forest Service, include restoration of watershed function, addressing legacy road networks and providing wood fiber and forest products to support local economies.

“In the context of this project, when we say ‘resiliency’ we very much mean it in the ecological sense of the term,” says Anderson. “For an ecosystem to be able to withstand disturbances and be able to bounce back—we have fire, we have insects, we have disease.

“We want our forests to be better suited to respond to those, particularly in light of a warmer climate.”

The agency’s plan has led to singeing public debate.

“When you’re faced with the challenge of managing public resources for multiple uses, you’re never going to 100% satisfy everything or everyone—and we’ve certainly been hearing from all of those folks,” says Anderson, who describes meetings attended by Tribes, stakeholders, county commissioners, conservation groups and other interested locals during earlier stages of the project as “robust.”

Thinning the forest, in part via logging, to reduce fuels for potential fires is one objective of the project.

If there’s a common point that all groups can rally around, Anderson hopes, it’s “defending a fire-adapted ecosystem from responding as severely as we’ve seen in a lot of landscapes across the West. Either that’s going to happen with some strategic thinning of undergrowth, small trees and prescribed burning at this point—or the area will be reset with a large wildfire.”

So how does the agency respond to a “forest resiliency project” being called a “logging project” by local conservationists?

“I don’t try to speak for others representing our project however they do, or weigh too much into any misconceptions about forest management, restoration and health treatments,” says Anderson. “What we’re essentially trying to do here is set up the landscape to be prepared for the future. That’s the primary intent and goal—and that’s why we call it a resiliency project.

“We’re not proposing to cut up trees of 21 inches [diameter, meaning old growth]. We’re not looking to take big trees out of there.”

County budget implications

More than 2,000 feet deeper than the Grand Canyon, Hells Canyon is the deepest canyon in the country and one of the Pacific Northwest’s most beloved wilderness recreation hideouts.

This year marks the 50th anniversary of the 1975 passage of the Hells Canyon National Recreation Area Act, which preserves and protects the area.

“It’s ironic that 50 years ago, the HCNRA Act was passed in part to help address public concerns that a place like Hells Canyon was being mistreated, and here we are having some of those same conversations during a historic year,” says Dawson.

Objections to the project cover a range of issues, from trees to roads to money.

“I would like to salvage more burn trees than they’re allowing us to do,” says John Hillock, a Wallowa County commissioner and electrician based in Enterprise, Ore. “I think it’s a terrible waste to have a lot of things burn instead of putting them to good use.”

Wallowa County has over a million acres of federal land and a tiny tax base, says Hillock.

Timber sales could begin in late 2025 or, more likely, 2026.

“We have a $30 million budget with about $5 million dollars in property taxes to manage our county, so I see this project as serving two critical purposes—one of which is fire resilience to ensure that a beautiful area stays that way.”

Hillock also objects to shutting down forest roads in the area.

“The [environmental assessment] calls for closing 18 miles of roads as part of the forest plan revision, and the people have spoken out against that,” he says. “We’re not in favor of closing a whole bunch more roads that’ll inhibit us from cutting firewood, looking for a lost cow down there or hunting, fishing and recreating in the area.”

Conservationists are pushing to close more forest roads to protect wildlife corridors and reduce redundancy in an area served by over 350 miles of roads.

“In Hells Canyon, one and a half miles of road per square mile is the Forest Service standard,” says Dawson. “On regular forestland it’s two and half miles. Some parts of Morgan Nesbit, you’re looking at over six miles of road per square mile. So, that’s a problem—and I think also an opportunity for our community to sit down and come to an agreement about what makes sense, and we haven’t done that yet.”

Changes advocated by the Greater Hells Canyon Council have led to Forest Service amendments on the project that include developing a 25,000-acre wildlife corridor map, decommissioning 17.4 miles of defunct forest roads and reducing commercial logging acres by 20%.

“It’s a core responsibility of our organization to hold the Forest Service accountable and push for improvements to harmful projects. However, we also believe that it’s important to acknowledge when they make positive changes,” the organization wrote in an open letter to its supporters.

Big area, big decision

A final environmental assessment is expected from the Forest Service early this year, followed by a 45-day objection period, a resolution timeframe and a final decision targeted for late spring.

Once approved, summertime crews would head into the woods to begin marking boundaries of different treatment units, according to Anderson.

Timber sales could begin in late 2025 or, more likely, 2026.

“I suspect we won’t start doing a lot of treatment in terms of thinning or burning until the following summer season (2026) when the area’s accessible,” says Anderson.

Long view: The Snake River in Hells Canyon. Photo: Chad Case/Visit North Central Idaho

Meanwhile, a series of Hells Canyon 50th anniversary events will also be kicking off in upcoming months.

“We’re hoping to lead a number of special anniversary hikes, outings, rafting and camping trips this summer, so I’d encourage people to stay in contact with us and check our website,” says Dawson. “Anyone who hasn’t been here really needs to see and experience this place. It’s deeper than the Grand—and nobody knows about it.”

Nice job. Jamie!

P.S. Someone might want to check the dates on the GHCC website, the one referenced in the article about the BMT.

Friend, Mike

Historically these areas had an average fire return interval of 20 years or less which maintained open stands of mixed Ponderosa pine and open grasslands. Invasive Douglas fir, grand fir, and young pine now overwhelm the forest resulting in uncharacteristic stand-replacing fires. The solution is to aggressively thin and prescribe burn these stands. The GHCC should be more supportive of the effort to rehabilitate this area.

The 21 inch rule made some sense in the 1970’s when the USFS timber harvest level was unsustainable. It makes no ecological sense now. This rule has also driven the forestry industry out of NE Oregon making it nearly impossible for private non-industrial landowners to manage their land.