As wells run dry, the state says it needs more time and money to crunch numbers. Hard decisions await

Ongoing: Misty Buckley carries dirty water from her animals’ pens to water plants in her yard in 2021 in Klamath Falls. The Buckley’s house well ran dry during the historic drought still impacting much of Oregon. File photo: AP Photo/Nathan Howard

By Kendra Chamberlain. March 28, 2024. “We are not currently meeting Oregon’s water needs.”

That’s how the state of Oregon 2024 draft Integrated Water Resources Strategy begins.

The report’s message is clear—Oregon is facing water scarcity challenges. Stream flows are declining, groundwater in some areas is dwindling and contamination is jeopardizing other water resources.

The 200-page draft document, released earlier this month by the Oregon Water Resources Department (OWRD), delves into water challenges the state faces. The underlying message is hard to ignore: there’s too much demand for too little water.

Six of the last 10 years have been some of the driest the state has seen.

Climate change is “no longer a separate consideration for water management, but rather an integral part of planning, monitoring and project implementation,” according to the draft strategy.

Yet more than 20 years into the ongoing water crisis, there’s another message in the report. The OWRD—the state agency meant “to assure sufficient and sustainable water supplies are available to meet current and future needs”—needs more time and more funding to study the problem.

Wells going dry

In the summer of 2021, about a hundred wells went dry in southern Oregon.

The state began offering free water deliveries to affected homes in hopes of helping families hold out until aquifers recharged during rainy winter months.

But the water never came back.

Over the following year, hundreds more residents reported wells going dry in central Oregon.

There are now roughly 1,200 homes scattered across the state without domestic water supply.

The majority of dry wells have been reported in Klamath, Jackson and Deschutes counties, areas that have also experienced the worst of the drought over the past few years.

These areas have seen increased groundwater pumping by irrigators and decreased aquifer recharge, according to the OWRD.

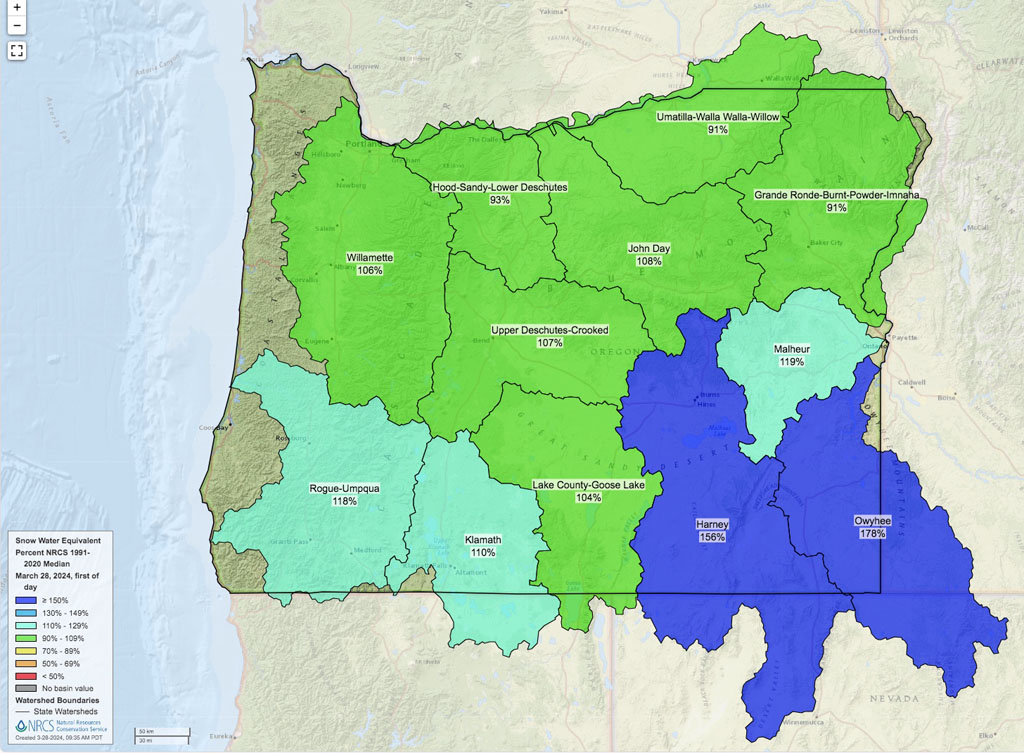

Glimmer: As of March 28, Oregon’s yearly snow water equivalent percentages compared with the 1991-2020 median were above average across most of the state. Map: Natural Resources Conservation Service

But wells are now going dry in counties in the wetter, west side of the state, including in the Willamette Valley.

“Wells across the state are going dry due to a number of factors including record drought, over-allocation of groundwater and limited recharge in some aquifers,” Tim Seymour, assistant groundwater manager at OWRD, told Columbia Insight in an email. “Most of the wells reported dry are domestic wells that are shallow in depth (<100 ft deep) and vulnerable to declines in water levels.”

Groundwater resources around the state are being stretched thin, according to OWRD.

The draft strategy document points out that in most locations in Oregon “groundwater aquifers are no longer capable of sustaining additional development without leading to declining supplies for existing water users and reducing streamflows where surface water and groundwater are hydraulically connected.”

As troubling, groundwater supplies are threatened in areas where the state has seen the most growth in the past decade.

The draft strategy emphasizes that “planning for future development must consider pressures on Oregon’s water resources, in terms of both water quantity and water quality and impacts to the environment and ecosystem services.”

The state is in the midst of revising its groundwater allocation rule to ensure that future groundwater withdrawal permits won’t threaten current supplies or hydrologically connected surface waters.

But the OWRD says it’s difficult to know exactly how much groundwater is left in any of the state’s basins without better data.

Deluge of data

The OWRD says it has multiple data gaps around water resources.

Groundwater allocations have been approved for decades without the state knowing exactly how much water is available; and the state currently isn’t able to track surface water use as closely as it needs for future planning.

The state has access to a network of roughly 600 stream-flow gauges across streams, canals and reservoirs that collect data on water levels in near real time.

But much of that data isn’t processed in a timely manner.

Central issue: Amid drought, Oregon is rethinking groundwater allocation strategies. Photo: Chuck Thompson

The OWRD says it hasn’t had the capacity to effectively process that data since the 1990s.

According to the department, there are “several years’ worth of water quantity and quality data” that still needs to be processed, analyzed and shared in order to be useful.

“These backlogs in unprocessed data arise largely from limited or inconsistent staffing and resources, shifting agency priorities and data systems, and the complexity of Oregon’s hydrology and geology,” Ben Scandella, hydrogeologist at OWRD, told Columbia Insight in an email.

The state is currently working on developing an online portal for water data that will make sharing data with agencies and the public more streamlined.

But the state will need to invest in managing that data in a way that can support future water planning decisions.

More money

Funding, staffing and resources remain perennial challenges for most of the goals outlined in the Integrated Water Resources Strategy.

The department says funding and staffing have been inconsistent, but also says significant progress has been made in recent years.

“Large water funding packages in the 2021 and 2023 Legislative sessions resulted in resources to make meaningful progress on many of the goals and their supporting actions,” IWRS specialist Crystal Grinnell said in an email. “There is still work to do to address the IWRS goals. There are still gaps in data to help us better understand our water resources.”

The draft document calls for more consistent funding and staffing to help OWRD better manage the water data and engage in inter-agency and local government coordination to ensure water resources aren’t over-allocated.

The final strategy must be adopted by the Water Resources Commission by September 2024 before a work plan can be developed.

In the meantime, the state will finalize new groundwater allocation rules over the next year.

The OWRD is accepting public comment on the draft on the water strategy until April 5.

Hello,

Thanks again for another wonderful Insight article. Groundwater restrictions should be enforced until the data has been analyzed. And why are users not paying for data collection and analysis? I will make formal comments.

Thanks, Michael Newsom

Wells have been running dry in Mosier for a number of years. This is not just a problem in other parts of the state.