If you spend time at Rockaway Beach, there are some things you might want to know about the water

Trickle down: Clearcuts like this one in Oregon’s Jetty Creek watershed damage more than just trees. Photo: Cosmo Jones

By Bob Atiyeh/Country Media. December 7, 2023. This is the sad tale of a watershed on the north Oregon coast.

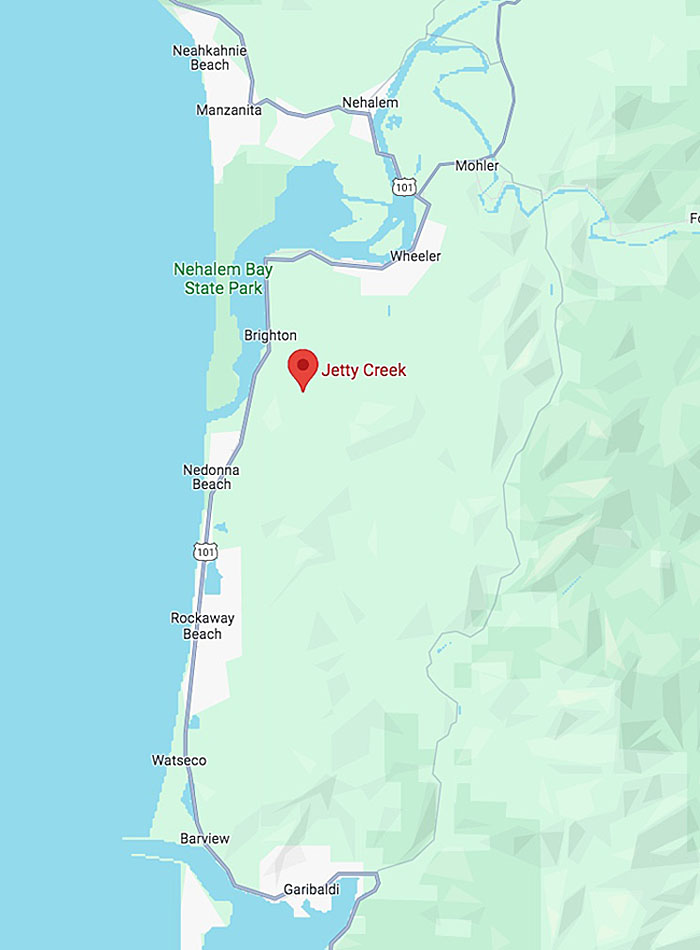

Jetty Creek is a small, coastal stream flowing into Nehalem Bay that provides drinking water to the communities of Rockaway Beach, Twin Rocks and Nedonna Beach.

In the late 1990s the forest canopy in the Jetty Creek watershed was healthy and intact and the stream ran clear and cold.

Over the past 20 years, this corporate-owned, 1,340-acre watershed has suffered a 90% loss of its forested canopy due to intense timber harvesting, and is now one of the most extensively logged watersheds on the Oregon Coast.

As a result of losing its protective forest canopy, Jetty Creek has experienced a significant decrease in stream flow during hot, dry summer months, and a significant increase in turbidity levels during wet fall and winter months.

During heavy rain events, these increased levels of turbidity can force the shutdown of the water treatment plant located at the lower end of Jetty Creek.

Studies have shown that removing even a relatively small percentage of forest canopy in a watershed results in erosion of the exposed soil along with an increased risk of landslides; with sediment washing into streams and filling them with a fine silt that clogs filters in water treatment plants.

In addition to clogging filters, the organic sediment in turbid stream water reacts with the chlorine used to disinfect drinking water, forming toxic chemical byproducts such as trihalomethanes (THMs) and haloacetic acids (HAAs).

Over the past two decades, the Oregon Health Authority and City of Rockaway Beach have issued multiple alerts about the local drinking water exceeding federal Environmental Protection Agency limits for these chemicals. The first was issued in fall 2004, a few years after Stimson Lumber Company began clear-cutting trees in the Jetty Creek watershed. By 2006, 30% of the forested canopy of the watershed had been destroyed.

Pricey fix

In 2009, the Oregon Health Authority informed the City of Rockaway Beach that a new water treatment plant with a “membrane filter” was needed due to high levels of turbidity. The city received $2.4 million in state and federal loans to pay for the new water treatment plant.

As the clear-cutting continued, turbidity increased with multiple violations of safe levels of THMs and HAAs. By 2011, 65% of the forest canopy in the Jetty Creek watershed had been destroyed.

Studies of Jetty Creek revealed that the volume of summer streamflow had decreased 30-40% compared to a baseline study conducted five years earlier.

Log out: On Highway 101, Rockaway Beach is a popular vacation destination for Oregonians from around the state. Photo: City of Rockaway Beach

Even after completion of the new water treatment plant in 2011—with the small communities obligated to repay $1.7 million of the $2.4 million cost—the Oregon Health Authority continued to issue water quality alerts about drinking water exceeding safe levels of THMs and HAAs.

In the fall of 2013, the Oregon Department of Environmental Quality reported that pesticide residue had been detected in untreated Rockaway Beach drinking water after aerial spraying of pesticides in the watershed.

By the end of 2013, Rockaway Beach had received more Oregon Health Authority water quality alerts than any other public water system on the Oregon Coast.

Killing the competition

The upper portion of the Jetty Creek watershed is owned by Stimson Lumber Company, headquartered in Portland. The lower section is managed by Chicago-based Nuveen Natural Capital (formerly GreenWood Resources) for Lewis & Clark Timberlands.

Private timber companies own almost 50% of the watersheds in western Oregon supplying drinking water to downstream communities, and almost 60% of the drinking water systems tested in Oregon had detectable levels of pesticides in their water.

After cutting down all of the trees in a clear-cut, the denuded land is sprayed with powerful herbicides to kill young deciduous trees such as red alder.

Red alder is a “pioneer species” and one of the first trees to regenerate after a forest is destroyed; helping to anchor the exposed soil against erosion.

Because these trees are able to “fix” large amounts of atmospheric nitrogen into the soil, the enriched soil allows other plant species to grow and thrive. Stands of red alder can serve as natural firebreaks during low- to moderate-intensity wildfires, as these deciduous trees are much less flammable than conifers.

But red alder grow rapidly and compete with the desired commercial monoculture of conifer species planted by private timber companies after clear-cutting, so red alder trees are routinely destroyed with herbicides, along with native vegetation such as elderberry, salmonberry and thimbleberry.

Altered state: A 2022 view of private timber land in the Oregon Coast Range. Clearcuts abut the boundary of Saddle Mountain State Park. Photo: Richard Felley

These herbicides are usually applied using helicopters, and the extremely toxic chemicals can persist in soil, migrate into groundwater and drift on air currents directly into streams and onto adjoining private property.

Manual ground-level herbicide spraying is hazardous not only to the environment but to the people applying it.

Rodenticides are sometimes applied to recently replanted areas to kill native mountain beaver (not an actual beaver), which damage and destroy young trees, with potential secondary poisoning of non-target animals such as owls and raptors.

According to a 2021 Portland State University study, pesticide residue from the types of pesticides used in forestry have been detected in clams, mussels and oysters in intertidal areas along the Oregon Coast and adjoining coastal streams draining from areas recently sprayed with pesticides.

Along with the decreased volume of summer streamflow, an increase in water temperature in the streams flowing through these deforested lands is harmful and can be lethal to populations of endangered coho salmon and wild steelhead.

Hydrologists have recently published studies showing a tenfold increase in stream sediment in logged areas compared to uncut areas, and an Oregon State University study found a 50% decrease in streamflow in 40-year-old commercial tree plantations, compared to diverse forests more than 100 years old.

The “Private Forest Accord” taking effect in 2023 and 2024 made incremental changes to the antiquated Oregon Forest Practice Act enacted in the early 1970s, but even with these modest changes, Oregon’s forestry laws still provide weaker protections for rivers and streams and continue to lag behind more protective and comprehensive forestry laws in Idaho, Washington and California.

Profits up, tax revenue not so much

Young trees in commercial tree plantations sequester far less atmospheric carbon than older trees, and OSU studies have shown that wildfires can burn far hotter in dense stands of even-aged commercial tree plantations compared to diverse, intact, mature native forests.

While Oregon’s wood products industry employs about 3% of the state’s total workforce and contributes around 4% of its GDP, it’s also Oregon’s largest single source of CO2 emissions, contributing 35% of the annual total; more than transportation, agriculture and wildfires combined.

A 2020 article published in The Oregonian, Oregon Public Broadcasting and ProPublica stated that “in western Oregon, at least 40% of private forestlands are now owned by investment companies that maximize profits by purchasing large swaths of forestland, cutting trees on a more rapid cycle than decades ago, exporting additional timber overseas instead of using local workers to mill them and then selling the properties after they’ve been logged.”

More corporate timber money gushes into the campaign coffers of Oregon legislators than any other state legislature in the country.

The Jetty Creek watershed is located within a popular vacation area on the northern Oregon Coast. Google Maps

In the late 1990s, timber corporations successfully lobbied the Oregon Legislature to eliminate the severance tax on timber harvest.

This massive financial windfall for the corporate timber industry has deprived small rural communities of an estimated $2 billion in funding for critical public services over the past two decades. The timber industry now pays less than 1% of the severance taxes it paid in the 1990s.

In late 2013, the EPA and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration issued a finding that the Oregon Forest Practice Act failed to protect water quality in Oregon’s coastal zones, and in 2015 found that the Oregon Forest Practice Act was not in compliance with the federal Clean Water Act in coastal areas.

In 2014, after more than 80% of the Jetty Creek forest canopy had been destroyed, the City of Rockaway Beach completed construction of a $400,000 pressurized sand filtration system to enhance the treatment of their drinking water; with water rates almost tripling between 2009 and 2017 to help pay for the new water treatment infrastructure.

Some north coast communities, such as Astoria, Cannon Beach and Arch Cape, own the watersheds supplying their drinking water.

But many other coastal communities aren’t so fortunate.

Being completely dependent on private timber corporations for the quality and quantity of their drinking water, many of these small communities are left to pay the bills for expensive improvements to water treatment facilities. At the same time, un-milled logs from the harvest of Oregon’s precious natural resources flow unrestricted to the People’s Republic of China, and the profits flow to corporate headquarters usually located hundreds or even thousands of miles from the Oregon Coast.

Apocalyptic feel

Less than a century ago, hundreds of thousands of acres of temperate rainforest on the north Oregon Coast and throughout the north Oregon Coast Range remained road-less and unlogged.

The forests contained massive, centuries-old trees, many of them more than 10 feet in diameter.

We’ll never know what was lost within the depths of these ancient forests, as almost all of them have been destroyed by logging or the massive fires ignited by logging operations.

What was once one of the greatest forests on the planet in terms of biomass-per-acre has been converted to hundreds of thousands of acres of single-species, even-aged commercial tree plantations that are cut down every few decades.

Cut down to size: Logging operation in Jetty Creek watershed in 2020 on Oregon Coast. Drone photography: Dr. Trygve Steen

Even if left alone, it’s doubtful this temperate rainforest has the ability to regenerate into the healthy, biodiverse ecosystem it once was.

Timber corporations are already feeling the effects of a rapidly changing climate as their monoculture plantings of young Douglas fir are stunted by fungal Swiss Needle Cast disease and their plantings of young Western hemlock succumb to the hotter and drier summers.

This past summer, the Jetty Creek watershed had an apocalyptic feel, as smoke from Canadian wildfires drifted south along the Oregon Coast, creating a hazy, brown backdrop to the stumps of the denuded forest.

It was a harbinger of the natural disasters ahead as we continue our collective journey down the dead-end path of denial.

Reprinted with permission from the Cannon Beach Gazette, this article was first published on Sept. 1, 2023. Country Media, Inc. All rights reserved.

I really enjoyed the explanations in this article, thank you!

This is terrible. I thought Oregon was more progressive than this and would protect its native forests.

This article is concise, accurate in its descriptions, and should be required reading for all elected public servants at local, state and federal levels. Why? Because it debunks the mis- and dis-information mythologies generated and perpetuated over decades by industrial logging interests, Farm Bureau, Chambers of Commerce, and OSU’s Dept. of Forestry who are invested in maintaining the status quo in law and policy.

What is needed? The Oregon public must wake up to the realities that timber is NOT a giant in Oregon’s economic generators. Deforestation and destabilization of eocysystems and watershed lands demands immediate protection starting with a ban on clear cutting, no new logging roads, and public ownership of watersheds to remain standing forests.

Regenerative farming practices for food crops and inclusion of innovations of fast growing fiber crops to be used for paper making, building materials, or pellet production should be a visionary focus to replace the cutting of living trees that are “working” for the planet by doing what they do best – photosynthesizing to provide oxygen, habitats, stream protection, cooling of land, and holding of water to ensure stream flows even in dry season or drought.

It’s time to change state laws to protect all standing forests instead of protecting income sources of timber and chemical industry or state agencies. Life on this planet requires intact and balanced systems of nature that must be protected from human greed and ignorance.