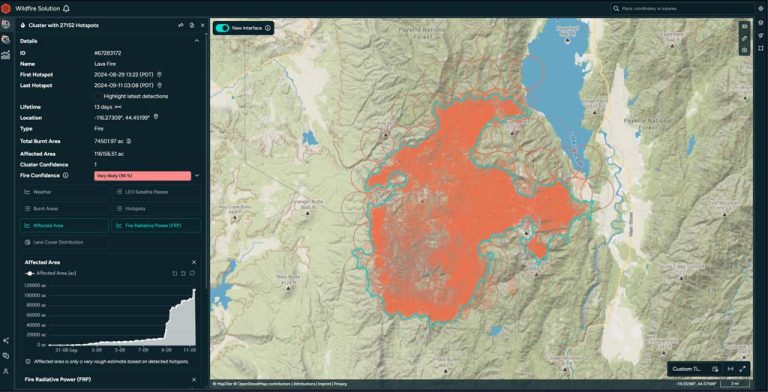

Without a major policy shift, more private homes will burn and more public money will be spent trying to protect them

Not all can be saved: A Fire Boss amphibious air tanker dumps 200 gallons of water over the Tunnel 5 Fire. The house in flames (left) and another home (obscured by smoke) directly beneath the water drop were completely destroyed. Photo: Jurgen Hess

By Jurgen Hess. August 3, 2023. On July 2, the Tunnel 5 Fire began in Underwood, Washington, about two miles west of the town of White Salmon in the Columbia River Gorge National Scenic Area.

Before being 80% contained by mid-July, the fire scorched 529 acres and destroyed 10 structures, mostly homes. At least 40 fire engines, 256 firefighters and other personnel, five helicopters, six dozers and 16 water tenders were employed to fight the blaze.

The cost is still being calculated, but a single retardant drop by jet airplane on the Tunnel 5 Fire cost as much as $12,400.

The expense for fighting the 2017 Eagle Creek Fire on the Oregon side of the Columbia River Gorge eventually reached $40 million.

For two weeks, the Tunnel 5 Fire provided a shocking and unsettling sight as flames and smoke billowed above a stretch of the Columbia River dotted with large, cliff-top homes.

But it was hardly unprecedented.

In 2007, the Broughton Fire burned 200 acres and seven structures (including five houses) in the precise location.

That fire was caused by the BNSF Railway Company’s grinding of nearby railroad tracks. “Track grinding” or “rail grinding” repairs deformities and corrosion of rail tracks due to heavy use. The process creates sparks.

The cause of the Tunnel 5 Fire remains under investigation.

Close call: The Tunnel 5 Fire blew up steep slopes carried by fuels of trees, shrubs and grass. This house was fortunate to be spared from the fire. Photo: Jurgen Hess

Two wildfires in the exact location in just 16 years—is this simply a coincidence, a supreme stroke of bad luck?

Unfortunately no.

The Broughton and Tunnel 5 Fires burned, proved so difficult to fight and were wildly expensive to contain for similar reasons.

Might another catastrophic blaze burn in the same area in the near future?

Unfortunately it’s likely.

The reasons have to do with the geography of the area around Underwood and particular regulations that govern private property in the National Scenic Area.

But they also point to broader issues involving the encroachment of residential homes in heavily forested areas, and the way the U.S. Forest Service currently prioritizes private real estate (i.e., houses) over public resources (i.e., trees and surrounding habitat) when fighting fires.

Is such a policy wise? Is it in the public’s interest?

With national insurance companies beginning to refuse to issue policies for homes in some parts of the country due to “growing catastrophic exposure,” is it time to reconsider the construction of houses in fire-prone areas and the way we fight nearby fires when they inevitably come?

Recipe for disaster

Located along Washington State Route 14 at the confluence of the White Salmon and Columbia Rivers, Underwood is an unincorporated community within the Columbia River Gorge National Scenic Area. Its position atop a set of bluffs commands fantastic views of the Columbia River Gorge and, across the river into Oregon, Mount Hood.

But the bluffs atop which the community sits are so steep they form a nearly vertical wall.

In summer, these slopes are covered with highly flammable dry grass, brush and trees. One source of ignition and a decent wind are all that’s needed to send fires roaring up the hillside. (In the first days of the Tunnel 5 Fire, winds gusted between 35 and 40 mph.)

Heaven meet Hell: Slopes below Cook Underwood Road burned right up to the hilltop houses. Photo: Jurgen Hess

At the bottom of the bluffs, SR-14 and adjacent railroad tracks—both proven and potent sources of ignition—parallel the river.

At the top of the bluffs, Cook Underwood Road is lined with over 50 houses, each surrounded by forest, trees and brush.

The recipe for disaster is obvious.

“We can’t stop the fires, [we] shouldn’t build there,” Robin Dobson, a retired U.S. Forest Service ecologist who worked in the Columbia River Gorge National Scenic Area for 24 years, told Columbia Insight after the Tunnel 5 Fire. “We need to use our common sense.”

“Nobody thinks [fire] can happen to them, but the reality is that it does,” said Dan Harkenrider, USFS National Scenic Area manager from 2001 to 2011.

How Firewise are we?

In 2002, recognizing the growing problem of wildfires in rural residential areas (especially California), the National Fire Protection Agency created an educational program called Firewise Communities USA. The idea was to teach homeowners best practices for how to live “fire wise” in Wildland Urban Interface (WUI) areas as a way to mitigate potential wildfire losses.

Firewise measures include removing shrubbery and trees close to home ignition points by creating a “lean, clean and green landscape” zone; using fire-resistant building materials; screening house vents; and keeping gutters free of burnable material.

Dan Richardson, Underwood Conservation District, Climate and Community Resilience lead, administers the Firewise program in Underwood by doing a wildfire home hazard assessment.

Passing grade: Dan Richardson (right) conducts a Firewise review at the Columbia River Gorge home of Luci Walker and Kevin Widener. Photo: Jurgen Hess

On a recent visit to the home of Luci Walker and Kevin Widener (north of Cook Underwood Road, not in the immediate area of burned houses), Richardson walked around the perimeter of the home looking for vegetation too close the house.

After explaining that most house fires are started by glowing embers, he noted that all vents in the house were well screened and that the house siding was made of unburnable cement board. The gutters were largely empty of burnable debris. There was no bark dust, which is very flammable.

A small juniper plant was recommended for removal.

A question arose of what to do about a long line of large Douglas fir trees on the east property line. Those trees could carry a crown fire.

Richardson concluded that picking up limbs and debris, cutting branches to a height of 10 feet and thinning out smaller trees would help reduce fire risk.

Overall, the homeowners got a report that the house met Firewise standards, with a few recommendations for improvement.

Conflicting guidelines

The Columbia River Gorge National Scenic Area Management Plan includes provisions for implementing Firewise practices.

“The reviewing agency shall provide information on Firewise standards to landowners at the time of application (for a building permit),” states the plan. “Landowners shall be encouraged to incorporate Firewise standards in their proposal.”

Fire-risk directions are also included in the Gorge Commission’s recently adopted Climate Change Action Plan.

But Lisa Naas Cook, a planner with the Gorge Commission, says meeting National Scenic Area standards of scenic preservation and reducing fire risk is a tricky dance.

That’s because homeowners in the Gorge are bound by National Scenic Area Management Plan regulations that require houses be screened with trees or other vegetation to meet scenic-protection measures.

Air war: Black spots in the sky during the Tunnel 5 Fire are hot embers driven by upslope winds. During wildland fires, embers are the primary ignition source for house fires. Photo: Jurgen Hess

In a way it feels like a trap, with Firewise and National Scenic Area guidelines appearing to be at odds.

“Absolutely there is a conflict between fire safety (and scenic standards),” said ecologist Dobson.

Cook said the Commission plans to take a closer look at the issue during its next Management Plan review.

According to the Gorge Commission’s website, the Commission can amend its plan “if it finds that conditions in the National Scenic Area have significantly changed.”

At this time, however, there is no proposal on record to amend the plan.

During the public input phase of the Climate Change Action Plan development, several members of the public argued for more stringent standards to reduce fire risk.

Janet Wainwright, a former Gorge commissioner, wrote: “Mandate (not suggest) all new construction adhere to Firewise standards. Make this one of the requirements of application approval.”

But such measures can do only so much to prevent wildfires from burning homes built within forests and other wilderness areas.

“Homeowners who live in forested settings must take responsibility and prepare their property to survive wildfire rather than relying on firefighters to save their homes,” said Jack Cohen, a USFS research scientist. “Because during intense fire conditions firefighters will likely be overwhelmed.”

Private property vs. public treasure

When fighting fires, USFS policy dictates that saving human lives is the top priority, followed by saving property, such as houses and businesses.

This became a problem when the Tunnel 5 Fire struck. Firefighters weren’t sent onto the steep slopes below the Underwood houses due to safety risks.

“It’s just too hazardous for firefighters to work on the steep ground,” Bobby Shindelar of Northwest Incident Management Team 12 told Columbia Gorge News.

Instead, at a great financial cost, aircraft dropped water and retardant on the steep slopes.

Extreme slopes: It’s not just flames and smoke that imperil firefighters. Treacherous inclines, like those faced by these Tunnel 5 firefighters, introduce another level of danger. Photo: Wash. DNR

Firewise is good practice, but after an event like the Tunnel 5 Fire it’s reasonable to wonder how much homeowners can realistically do to prevent the loss of property constructed in such an obviously precarious place.

Shifting attitudes of insurance companies may also become a factor in the way we view fighting fires.

On May 26, State Farm Insurance announced it would no longer accept applications for home and business insurance in California due to “historic increases in construction costs outpacing inflation, rapidly growing catastrophe exposure and a challenging reinsurance market.”

Some of those increased construction costs and catastrophic exposures are related to high fire risk and requirements to make new homes fire-safe.

In conversations with Columbia Insight, County Commissioner Tom Lannen, Scenic Area Manager Harkenrider and several Tunnel 5 firefighters said they believed insurance policies would be a “check” and on future construction in fire-hazard zones.

But David Waymie, director of the Skamania County Public Works and Planning Department, which administers building permits in the area of the Tunnel 5 Fire, said his department is unlikely to require fire-protection measures for homes being rebuilt in the wake of the fire.

But, he said, “there is a risk in living in the forest. While the view is tremendous, there is a fire danger.”

Homeowners in Skamania County have two years to start the process of replacing a burned house.

Same old, same old?

Another fire in Underwood is likely because conditions that led to the previous two fires will remain stable.

SR-14 isn’t going anywhere. Neither are the railroad tracks nor the steep, vegetated cliffs directly below the community.

“For maybe 10 years or so after a fire, fuels and risks are lower. But with hotter and dryer weather fire risk is increasing, especially on these slopes,” said Lorretta Duke, South Zone fire management officer of the Gifford Pinchot National Forest, a portion of which is located in Skamania County.

Duke also points to rail-grinding operations. “Consider timing of grinding to not do that during high fire danger times,” she said.

“There needs to be conversations with Burlington Northern as to their track-grinding procedures,” Skamania County Commissioner Tom Lannen told Columbia Insight when asked about preventing future fires in the area.

Others are more blunt in their assessment of construction and rebuilding of houses destroyed or damaged in areas of high fire risk.

“It seems crazy to build a new house in this fire-risk zone,” said Harkenrider. “Where is the line where people shouldn’t be allowed to build?”

Metal roofs are not permitted in the Scenic Area. This is a rule that needs to be reevaluated yesterday. It is absurd.

Conifers are particularly incendiary. Removal of fir and pine downslope and near to buildings would seem to make sense. This is also not allowed by the Scenic Area regulations. They need to be revised. All vegetation is not alike in its potential threat to be ignited in a wildfire. Deciduous trees ignite less easily than conifers.

Hi Blayney, you’re right that deciduous trees — our oaks, maples, dogwoods, etc — don’t carry fire or torch hot like our pines and firs; we advise people who are strengthening their defensible space to have a bias for trees with leaves over conifers. It’s not quite true that people in the Scenic Area cannot remove trees — just look at the relatively open areas atop Underwood bluff where the houses are. The Scenic Area rules are not the problem, IMO. Rather, I’d emphasize the need for individual homeowners to gain the awareness of how to reduce ignition sources on and immediately around their structures. Look for the gutters full of pine needles, the decks crammed with flammable furniture, the firewood stacked on the front porch, the yard full of highly flammable juniper bushes, etc. As fire researcher Jack Cohen says, it’s the little things that ignite from wind-blown embers and burn down houses most often. Also – support your local volunteer rural fire district!

Really?? The article goes on and on about people having homes where they shouldn’t due to fires that ‘will’ happen. What I expected to see was an article about ‘why’ the fire happened and how to stop that in the future! Ie; how the railroad can make sure the tracks don’t create sparks ?

Thank you for the comment, Stephanie.

Per DNR, the cause of the fire is still “Under investigation”. Sometimes the agency determining a fire’s cause takes some time to make the final determination.

As to track grinding, Lorretta Duke is quoted, “consider grinding to not do that during high fire danger times.” Also, Skamania County Commissioner Tom Lennon says, “There needs to be conversations with Burlington Northern as to their track-grinding procedures.”

Jurgen Hess, author of article

As I heard in a talk about fire in the Rockies, these issues are likely to continue to rise. It is counties that permit the houses and get the benefits of taxes, while the cost of fire fighting is largely state and federal funding. Perhaps making local jurisdictions responsible for fire fighting costs might change their willingness to permit houses almost anywhere.

It may well be that, like Florida and California, insurance companies will not be able to get reinsurance, and will drop covering houses in hazard-prone areas.

As for metal roofs, yes, the geniuses at the Gorge Commission veto those because they are “too reflective.” This includes roofs made of cor-ten steel, which forms a rust coating within a year and turns orange. I know about cor-ten because our house (thankfully not in the scenic area) has one and gets constant compliments for its beauty, and because we have friends in the scenic area who were told they couldn’t put one on.

So Dan Richardson, yes, the regulations can be a problem. Want people to be fire aware? Absolutely. To care about the little things? You bet. But it’s okay to prohibit cor-ten roofs because, um, why again? When we moved here we took care to avoid buying land in the scenic area, not because what we would build would be unscenic, but because we were told that their vague, inconsistent, nonsensical reviews add a year and $50,000 to $100,000 to the cost of a house.

Duncan Foley, you don’t live in the Columbia Gorge, do you? We pay taxes for fire protection here. There is a lot to say about all that, but the idea that we don’t pay for fire protection is utterly false.

Finally, I am interested in an article about fire retardant mixed with water and sprayed on wooden siding. I would read it carefully, as long as it was objective and fact-based.

A note about cor-ten’s color. It’s not citrus orange, but darker, more like orange-red, and blends very well with the grasses in our meadows.

Jurgen,

I just drove south on I-90 through the Medical Lake area just SW of Spokane. Well over 100 homes were lost. Different terrain and fuels for the most part. However, grass, conifers and wind played their parts. Luckily, folks had some warning and roads (paths to safety) were adequate. Hood River- do we have adequate warning systems, roads capable of proving egress for those living here and tourists who may not be familiar with local road systems? Is our local government (city and county) aggressively taking steps to investigate and mitigate the risks that are present?

Maui Meyers recent comments in the Gorge News – August 23 about the Lahaina catastrophe are worth reading imo.

Terry Egan

Hood River

@Jack Swift – there are Cor-Ten roof’s in the scenic area. The corner of Sooter Rd and Corner Rd for instance.

The permitting process is not fun I am told. I’ve been down to Stevenson several times for remodel permitting and getting clearance on a plan for thinning. In general the folks I worked with down there were helpful and a couple of times pointed out places where I could make the process more efficient and less costly. (Rather unlike my experiences with vehicle registration…)

I sure have heard the Gorge Commission stories. Most homeowners in the scenic area have. Our experience has been generally positive though. We are off Cooper Ave on the lower shelf in Underwood and are visible from at least 2 of the checkpoints the GC uses when evaluating plans.

The functional appropriateness and suitability of a metal roof to handle Columbia Gorge weather is exceptional. No other roof type can boast the same low maintenance, snow shedding ability, fire protection, wind resistance and combined service life for the price. All are major factors here where we live. It is grossly unreasonable to mandate the loss of these attributes for a temporary and minor glare. Banning this roof type in Key Viewing Areas (KVAs) to visually appease perhaps a momentary glance of passersby’s is regressive. Especially when many earth tone color options are available for metal roofing. The combination of textured, flammable surfaces on our homes, the required visual screening and uncared for federal lands, with mounting ground and ladder fuels is a telling concern. Is there conflict between visual screening and fire-defensible spaces? How attractive is a burned-out KVA? Is looking good more important than safety or environmental stewardship?

Actually, metal roofs are allowed in the scenic area. However, each county (except Klickitat, their permits are issued through the CRGC office) can have their own restrictions as long as they are not less restrictive than the management plan ordinances. Skamania County chose the no metal roof restriction.