As Oregon’s mule deer population drops, large solar installations and a warming climate have emerged as new threats

Catching some rays: Sunny skies may be proving problematic for mule deer populations. Photo: Nick Myatt/ODFW

K.C. Mehaffey. June 29, 2023. When the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife last updated its Mule Deer Management Plan in 2003, game managers saw what appeared to be a fairly stable—although fluctuating—population. Severe winters and droughts in the 1990s were predictably followed by population declines, but by the early 2000s, mule deer numbers were again on the rise.

But instead of making a comeback in the new century, Oregon’s mule deer population entered a long, steady decline for the next two decades.

Last year, the agency estimated the mule deer population at 162,600 animals. It’s a significant drop since mule deer numbers peaked at 306,000 animals in 1980.

The population is now less than half of the agency’s objective to have 344,200 deer at the end of hunting season.

As Oregon writes a new draft management plan for mule deer, impacts of climate change and the potential loss of habitat from new solar farms have emerged as the latest threats to this iconic deer of the West.

“Mule deer have been in decline—long-term decline—across most of their range, and Oregon has experienced this decline along with many other states,” says Brian Wolfer, ODFW’s acting wildlife division administrator. “We want to turn this trend around, and we want to invest in our mule deer and improve our mule deer populations.”

Wolfer was speaking at an April 17 webinar—a kickoff for the release of the first three chapters of the new draft plan. Two more chapters and another webinar came in mid-June. More chapters and additional webinars will continue through this fall, with a new plan tentatively scheduled for adoption early next year.

The last chapter—scheduled for release in September—will be on the anthropogenic impacts, including climate change and energy development.

But the issues of solar farm siting and warmer weather are also being discussed.

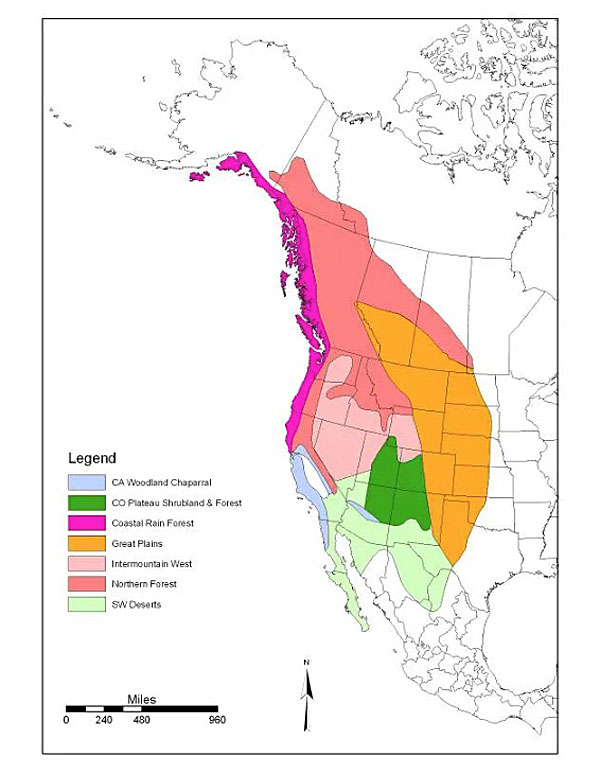

Mule deer eco-regions: Map: WAFWA Mule Deer Working Group

As Oregon prepares to get significantly more energy from renewable sources, the rapid construction of new solar farms is on ODFW’s radar, says Josh Smith, ODFW’s mule deer coordinator.

Solar farms take up vast areas of land, and that development is likely to take place in eastern Oregon’s mule deer country, where there’s more undeveloped land and more reliable sun.

“Right now, the literature is pretty sparse on impacts from solar farms and best management practices to mitigate some of the detrimental effects on mule deer and some other wildlife, so we’re actively looking at ways to increase our knowledge of this,” says Smith.

It’s a big issue across the West. Energy development has been identified as the top priority of a mule deer working group of the Western Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies.

Direct impacts from a warming climate are also taking a toll on mule deer populations. Climate change is not mentioned in Oregon’s 2003 Mule Deer Management Plan. But the new plan notes that changing conditions have already reduced spring growing seasons.

Carrying capacity of land in decline

Over the years, wildlife biologists have paid close attention to mule deer winter range.

But Smith says that summer range is equally important.

As migratory animals, portions of Oregon’s mule deer herds travel long distances to enjoy the greener grasses at high elevations each summer, and then return to places with less severe winters for the colder months.

Handling it: Josh Smith, ODFW mule deer coordinator. Photo: ODFW

At their summer ranges, deer must put on significant body fat to make it through the next cold season.

“If they don’t come into winter in pretty good shape, they’re kind of in trouble and can be susceptible to over-winter mortality,” says Smith.

He says preliminary data from a recent ODFW study found that mule deer on the Murderer’s Creek range, south of the John Day River, have an average body fat of 10.1% going into the winter months, with a range from 4.9% to 17.6%. Other research indicates that mule deer need about 12.5% body fat to make it through the winter, Smith says, and only 21% of the mule deer in this range met that criterion.

Biologists are finding the carrying capacity—the ability of the landscape to support mule deer—has slowly declined since the 1990s.

Part of the reason may be that the plants they rely on are not as nutritional.

Recent research from ODFW compared habitat data from the 1990s with data from 2015 to 2019. The study found that warmer and drier weather over the last 30 years resulted in the loss of two to three weeks of the growing season in the spring, when plants are going through a greening-up process, and another week in late summer, when plants turn brown and start to dry out.

“So really, we’ve seen it on both ends,” says Smith. “The growing season has kind of compressed. We’re losing about a month.”

When does are pregnant, their nutritional needs are two- to three-times higher, and when they’re nursing their needs are four- to seven-times higher. Poor nutrition results in lower reproduction, and impacts adult survival.

“Ultimately, all these things interact to lower population performance and reduce population growth,” says Smith.

Other effects of climate change—such as larger and more intense wildfires, the spread of invasive plants and more variable precipitation—may also hurt mule deer survival.

Barriers to migration

While the impacts of climate change and clean energy expansion will be new to the plan, threats identified in the last plan remain, and some have become more problematic as Oregon’s human population has grown.

One of the chapters released in June dives into the problems that roads and fences cause for migrating deer.

Don Whittaker, ODFW’s ungulate species coordinator, says his agency spent the last 15 years trying to better understand the migration patterns of Oregon’s mule deer.

Predictable patterns: An ODFW staffer collars a mule deer doe for tracking migration. Photo: ODFW

Since 2005, ODFW put radio collars on more than 1,700 mule deer across eastern Oregon and have now mapped the migration corridors and seasonal ranges for the majority of migratory mule deer herds in the state.

Researchers followed some mule deer across three successive years and found they tend to walk in the same footprints and live in the same winter and summer ranges year after year.

“Fidelity to migration routes is extreme to the point they will rarely deviate from this migration route, even when they encounter barriers (like highways or fences),” says Whittaker.

Both are considered major barriers to migration. Throughout Oregon, roughly 6,000 deer are hit by vehicles each year.

The draft plan includes a map showing vehicle-deer collisions since 2010, which, it notes, could be used to design wildlife crossing structures.

According to the plan, fences also cause significant injuries and death to all age classes of mule deer, but most fencing in Oregon has not been adequately mapped.

The plan outlines strategies that include mapping Oregon’s major fencing across the mule deer range, and removing unnecessary fences or replacing it with wildlife-friendly fencing.

Hunting numbers down

The last chapter released in June describes the economic and social values of Oregon’s mule deer. It notes that as the state’s mule deer numbers dropped, so has hunting.

The number of mule deer hunters in Oregon peaked at 180,150 in 1970, and harvest peaked at 89,020 deer in 1968.

“Since the early 1980s, hunter numbers and associated harvest have steadily declined in response to reductions in opportunities available as mule deer populations have declined,” the draft plan says.

In 2021 (the most recent hunting survey available) 40,603 hunters got a license for mule deer, killing 13,892 deer.

Superb sight: Mule deer are often regarded as “The Deer of the West.” Photo: ODFW

The plan outlines the history of changes in hunting regulations, but says hunting isn’t considered a major source of population decline when it’s limited to killing bucks. A study in Colorado found that when adult male harvest was significantly restricted, the ratio of bucks-to-does increased, but there was a noticeable decline in the ratio of fawn-to-adult does.

“The study concluded that reduced harvest of bucks should be viewed as a tool to improve hunt quality for bucks, but not to improve population performance,” the plan states.

The chapter points out that mule deer are valued by many groups other than hunters.

However, the drop in hunters raises a major funding issue, since revenue to manage mule deer comes from hunting licenses. It identifies funding as an issue due to increasing conservation costs and declining participation by hunters, and suggests that alternative funding options should be explored.

The public is invited to comment on the draft plan, and receive updates when new chapters are released and additional webinars are held.

Conservationists are in the position to strongly advocate for siting solar collectors in cities and towns where they belong and where there are more than enough places to site them to generate all the solar energy and hydrogen we need.

Would love to see this article and also the article about the salmon on audio. The email we receive from Columbia Insight noted this article can be listened to, but I don’t see a link. Thank you–

Cite them on our roofs and eliminate the need for long distance transmission lines.

It is only when hunting license revenue is down, that ODFW starts to worry about wildlife populations. How about caring about sage grouse populations and non-game wildlife?