Department of Fish and Wildlife says the gray wolf should now be a state “sensitive” species rather than “endangered”

Out of the woods? Wolves like this young female tagged by state wildlife biologists in Washington’s Teanaway Valley are doing well, but their troubles aren’t over. Photo: Craig Monette

By Dawn Stover. June 5, 2023. Gray wolves are no longer endangered in Washington, according to the state’s wildlife agency.

On May 18, the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife issued a draft recommendation to reclassify the species from “endangered” to “sensitive,” a change that would bypass the intermediate designation of “threatened.”

“Wolves are doing exceedingly well in Washington,” said Julia Smith, wolf policy lead for the state agency’s Wildlife Program. “Nothing would change in our management” if wolves are downlisted, she told Columbia Insight.

Critics of the downlisting proposal say it violates the state’s wolf recovery plan and would remove protections for a species that still faces threats to its survival.

Growing population

Wolves were almost entirely eradicated from the Pacific Northwest by the early 1900s. Washington listed them as a state endangered species in 1980.

By the 2000s, a few dispersing wolves had migrated to Washington from Idaho and British Columbia. The first wolf pack with pups was confirmed in 2008.

The number of wolves in the state has continued to grow since then. According to an annual wolf report released in April, Washington had at least 216 wolves and 37 wolf packs at the end of 2022, including 26 packs with a successful breeding pair—a male and female with at least two pups surviving until the end of the year.

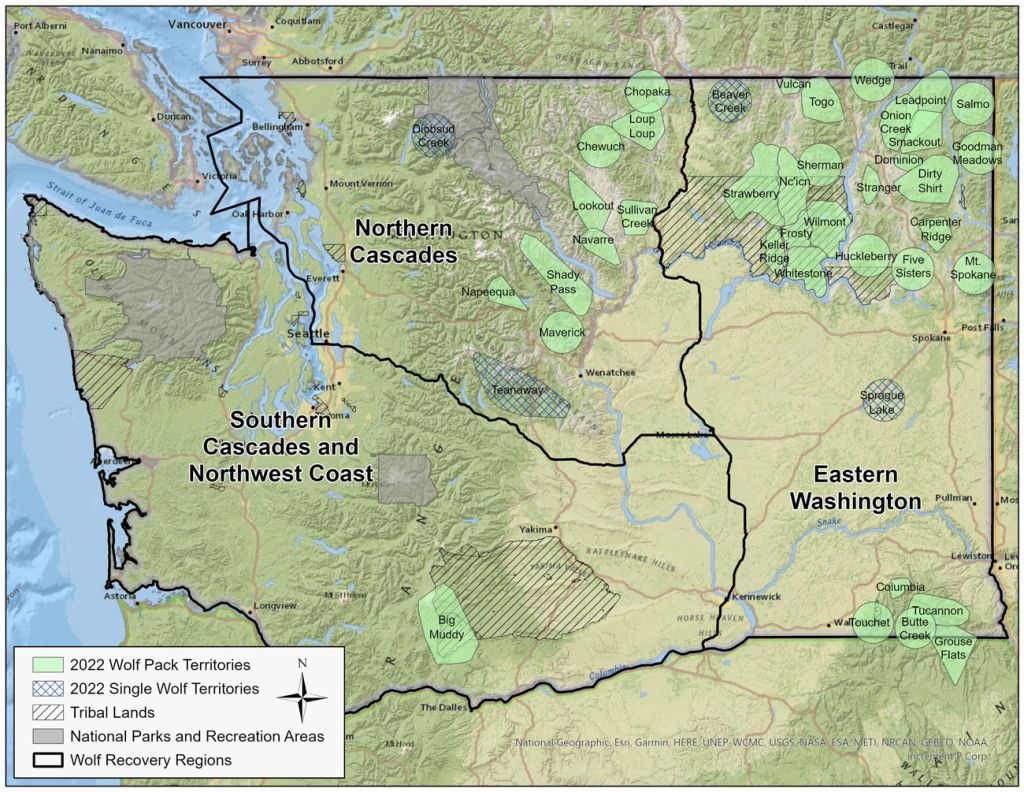

Known wolf packs at the end of 2022 in three wolf-recovery regions defined by the State of Washington. Map: WDFW

The state is divided into three wolf-recovery regions of approximately equal size.

Of the 26 successful breeding pairs, 20 are in Eastern Washington and six are in the Northern Cascades.

The third region—the Southern Cascades and Northwest Coast—had no wolf packs until the recent discovery of the Big Muddy Pack. The pack has one male and one female, but they have not yet produced any pups. Under the state’s definition, a pack can be as small as two wolves traveling together in winter.

Recovery targets not met

The draft recommendation for changing the gray wolf’s status notes that the state’s wolf population has “far exceeded” the population objectives outlined in the 2011 Wolf Management and Recovery Plan. However, the plan also includes criteria for the distribution and persistence of successful breeding pairs that have not yet been met.

The plan says the state should consider downlisting wolves from endangered to threatened when there are at least two successful breeding pairs in each of the three recovery regions for three consecutive years.

To downlist to sensitive status, the plan’s target is four breeding pairs in each region.

Because one of the state’s three recovery regions does not yet have any successful breeding pairs, neither of those targets have been met. That makes downlisting premature, according to wolf advocates.

“This misguided recommendation flies in the face of science, the law and the state’s own wolf recovery plan,” said Sophia Ressler, a staff attorney at the Center for Biological Diversity, in a statement issued by the nonprofit conservation organization.

State definitions

Smith said “we’re certainly open to” waiting until wolves meet those targets before changing the species’ state status. However, the Department of Fish and Wildlife is recommending a change now because of the legal requirement to review the status of all endangered species every five years.

The state defines an endangered species as one that is “seriously threatened with extinction throughout all or a significant portion of its range within the state.” Smith said the gray wolf no longer fits that definition, nor is it “likely to become an endangered species within the foreseeable future throughout a significant portion of its range”—the definition of a threatened species.

Smith said the best fit now is the definition for sensitive: a species that is “vulnerable or declining and is likely to become endangered or threatened in a significant portion of its range within the state without cooperative management or removal of threats.”

Sensitive status “still keeps wolves protected and allows for recolonization of western Washington,” Smith said.

[perfectpullquote align=”full” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]Reclassification would reduce the penalties for poaching or poisoning wolves.[/perfectpullquote]

The agency’s recommendation relies heavily on a new scientific model of wolf population dynamics in Washington.

Based on data from 74 radio-collared wolves in the state, the model makes projections about the likelihood of wolves colonizing western Washington and surviving over the next 50 years.

Critics note that the model has not yet been independently peer-reviewed or published. Funding for the study came from the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, which is advocating for the change in status.

Lower penalties for illegal killings

In Washington, changing the wolf’s state status would not have much effect in the western two-thirds of the state, where wolves remain federally protected as endangered species.

However, wolves are federally delisted in the eastern third of the state. There, Smith said the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife would continue to emphasize nonlethal approaches to managing conflicts with humans and livestock.

However, reclassification would reduce the penalties for poaching or poisoning wolves. The state penalty for illegally killing an endangered species ranges up to $5,000 and/or one year in jail. For a sensitive species, the penalty is a maximum of 90 days in jail and/or a $1,000 fine.

Illegal killing is on the rise, the Center for Biological Diversity says: “In the past decade, the state has confirmed an average of one to four illegal wolf killings each year. In 2022 nine wolves were illegally killed and at least six of those died in a single episode of intentional poisoning.”

Rewards totaling $53,900 have been offered for information that leads to a conviction in the poisoning of the six wolves in Stevens County, but there has been no discernible progress in the case.

Smith said the wildlife agency’s long-term goal is to get the state legislature to add wolves to a short list of species protected by a $2,000 criminal wildlife penalty against anyone convicted of killing them. The list currently includes bald eagles and four other bird species.

Ranchers have been pushing the legislature for reduced wolf protections, however. The Washington Cattlemen’s Association supported a failed bill earlier this year that would have allowed local officials to collaborate with the Department of Fish and Wildlife to manage gray wolves in some counties.

The Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife is seeking public input on its draft recommendation for downlisting through Aug. 16.

The Fish and Wildlife Commission, which would need to approve the recommendation, is currently scheduled to vote on it in October.