A male wolf that wandered into Klickitat County now has a female companion. Officials say it’s the first wolf pack in the region and may soon become a breeding pair

Wildlife biologists captured and collared gray wolf WA109M in 2021. They replaced his radio collar, which periodically transmits his location to a satellite, in January 2023. This photo was taken by a trail camera earlier this year in Klickitat County. Photo: WDFW

By Dawn Stover. April 7, 2023. Southwest Washington has its first wolf pack in a century. In an annual report released on Friday afternoon, the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife confirmed the new pack’s existence.

The Big Muddy Pack so far has only two known members, one male and one female. But that’s enough to meet the minimum requirement to be recognized as a pack: two or more wolves traveling together in winter.

It’s likely the pair will have pups soon, the wildlife agency’s wolf biologist Gabe Spence told Columbia Insight earlier this week.

Wolf pups are typically born in late April or early May.

The new pack is named after the Big Muddy Creek, which comes off the east side of Mount Adams and empties into the Klickitat River north of Glenwood, Wash. The creek lies within the Yakama Indian Reservation, and the Yakama Nation chose the pack’s name.

The wolves have established a territory in the southwest portion of the reservation and western Klickitat County, Spence said. It’s a sparsely populated area where local livestock producers have long been anticipating the arrival of wolves and are already testing strategies to prevent conflicts with cattle.

Back from the dead

After years of trapping, poisoning and government-sponsored bounty programs, the gray wolf was almost entirely eradicated from the Pacific Northwest by the early 1900s. The last wolves in the Columbia River Gorge were documented in the 1920s.

In the 1970s, wolves received federal protection under the Endangered Species Act. By the 2000s, a small number of dispersing wolves had migrated to Washington from Idaho and British Columbia.

Since 2008, when the first resident pack was documented in northeast Washington, the numbers of wolves and wolf packs have continued to grow each year.

[perfectpullquote align=”full” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]“A lot of people have been waiting for this for a long time.”— Gabe Spence, WDFW[/perfectpullquote]

According to the just-released wolf report, the state’s wildlife agency and Tribes counted a minimum population of 216 wolves and 37 wolf packs at the end of 2022.

Some 26 of these packs had successful breeding pairs—defined as a male and female with at least two pups that survived until Dec. 31. The average litter size is four pups.

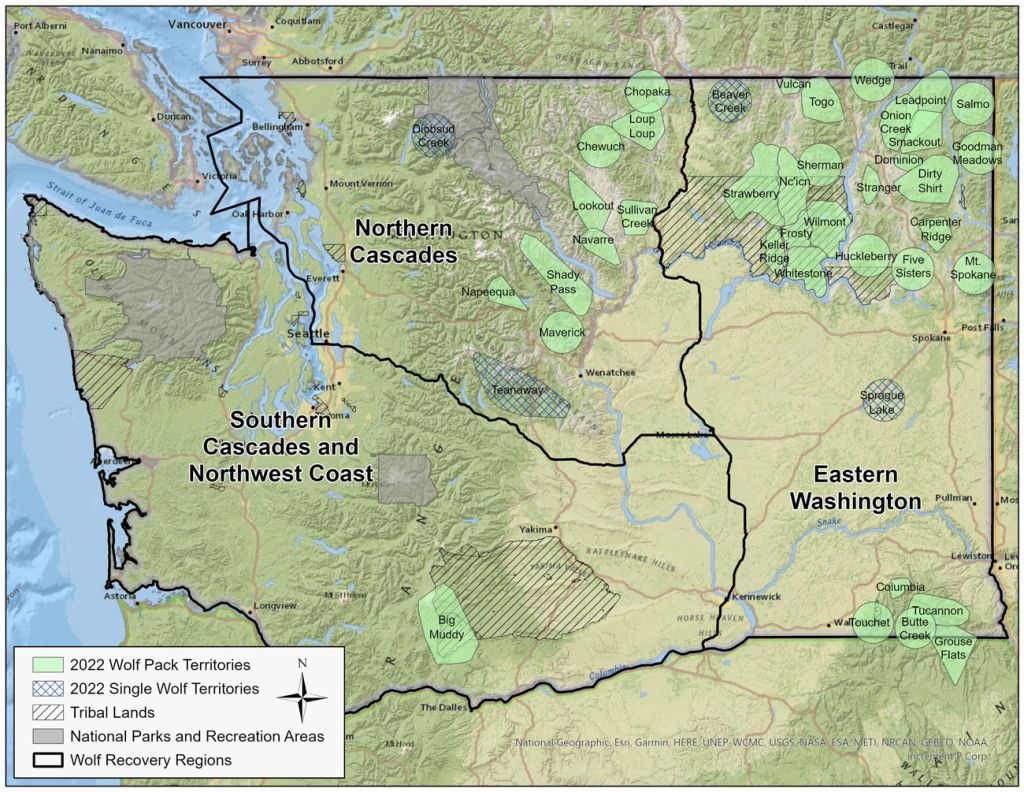

Washington’s Wolf Conservation and Management Plan, adopted in 2011 by the Washington Fish and Wildlife Commission, divides the state into three recovery regions: Eastern Washington, the Northern Cascades and the Southern Cascades and Northwest Coast. Until the discovery of the Big Muddy Pack, there were no documented wolf packs in that third region.

Most of Washington’s wolf packs are currently found in the northeast and southeast corners of the state, but wolves have been moving into north-central and central Washington in recent years.

Known wolf packs and single wolf territories in Washington at the end of 2022. The Big Muddy Pack is the first confirmed pack in the South Cascades and Northwest Coast recovery region. Map: WDFW

It’s very common for an adult wolf to leave its birth pack or another pack that it has joined for a while.

“Almost every wolf does that at least once in its life. That’s how packs start,” Spence said. “It’s the primary driver of population growth.”

Wolves typically disperse in search of a mate when they are two or three years old.

“Every wolf wants to be a breeder,” he said.

WA109M strikes out on his own

Five collared Washington wolves are known to have dispersed from their birth packs in 2021, including an approximately two-year-old male that Spence’s team captured and collared north of Ellensburg in January 2021. Dubbed WA109M, the wolf left his pack in central Washington later that year.

Male wolf WA109M photographed at night. His female partner has not yet been photographed. Photo: WDFW

WA109M wandered around for a while before crossing Interstate 90 and heading south through Yakama Nation lands. By late January 2022, he had traveled more than 325 miles and arrived in Klickitat County.

In April 2022, biologists monitoring WA109M reported that he was traveling in Klickitat and Yakima Counties with a second wolf, an un-collared animal of unknown age and sex.

The biologists don’t know where the second wolf came from or exactly when it met WA109M, but they determined it is a female by sending some of its scat to University of Washington researchers for genetic testing.

The two wolves have since spent their time hunting, sleeping and covering a lot of ground.

Wolf territories can be hundreds of square miles, and wolves use dens only for a short time when their pups are small.

It’s likely that a pair maintaining a territory together will produce pups this year, Spence said. About 70% of wolf packs produce pups in any given year.

Spence said he wouldn’t be surprised to get a confirmed sighting of a gray wolf almost anywhere in Washington at this point in the species’ recovery.

But confirming the existence of a pack that is maintaining a territory is far more significant, and finding the first pack in the only Washington wolf-recovery region that did not previously have one is “a big deal,” he said. “A lot of people have been waiting for this for a long time.”

Preventing conflicts with wolves

Conversations anticipating the arrival of wolves in Southwest Washington started long before WA109M showed up, and even before a photo taken in Klickitat County in 2014 was confirmed as a wolf sighting. (That wolf was never seen again.)

“Ten years ago, we started a range-rider pilot program with some of the livestock producers in Klickitat County, to get them familiar with the concept of range riding and monitoring livestock for the presence of wolves, because we knew it was coming,” said Todd Jacobsen, the local wildlife conflict specialist for the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife. A range rider is a cowboy or cowgirl who checks on herds to prevent conflicts with predators.

Range rider working in southeast Washington. Photo: WDFW

Jacobsen has since had many informal meetings to discuss wolves with local livestock producers around kitchen tables, as well as at organized meetings and workshops.

“There have not been any confirmed or probable livestock mortalities or injuries from these wolves in Klickitat County,” he said.

WDFW has a detailed protocol that outlines the tools and strategies the agency uses to reduce wolf-livestock interactions and support wolf recovery in Washington. The protocol includes methods for investigating suspected depredations.

Predators such as wolves and cougars have distinctive ways of killing their prey. To investigate a potential livestock depredation, specialists from the wildlife department shave and skin the carcass, looking for bite marks and subcutaneous hemorrhaging of muscle tissue, especially in the hamstrings and armpits. Tissue damage on a live animal attacked by a wolf will look different than damage to an already-dead animal scavenged by a wolf.

In the absence of telltale bite marks, investigators look for other signs of a wolf attack, such as fresh tracks, scat, hair caught on fences and blood or other physical evidence of a struggle.

Radio-activated guard (RAG) devices like the box and solar panel mounted on this tower activate when collared wolves approach them. They play loud noises or music and flash a strobe light to scare wolves. Photo: WDFW

Wolves feed primarily on elk, deer and moose. However, they will readily eat any livestock carcasses they find.

“They are really good at finding carcasses,” Spence said.

The wildlife department is working with livestock producers to emphasize the importance of quickly removing the carcasses of cattle that have died from disease, severe weather or other causes. Otherwise, these carcasses are likely to attract wolves, and the wolves might then become habituated to finding food in an area where cattle are pastured.

In April 2022, wildlife agency staff met with a rancher who had cattle near an area the collared wolf had been frequenting.

They emphasized the importance of carcass sanitation and offered help with securing carcasses.

In late summer of last year, another rancher’s adult cow was found dead in a large pasture that the collared wolf had been visiting.

Jacobsen conducted a necropsy of the carcass and determined that the cow had not been killed by a wild carnivore. He secured the carcass with electric fencing, to help prevent wolves from scavenging it before it could be removed.

Jacobsen has since received funding for a pilot project to remove carcasses from anywhere within the wolf pack’s territory in Klickitat County, at no charge to ranchers.

The department has purchased a dump trailer to haul carcasses to the regional landfill in Roosevelt, Wash., and Jacobsen has already made a few trips with it.

According to the wildlife department’s monthly report published in mid-March, the Big Muddy Pack was frequenting an area adjacent to a livestock calving pasture in the early months of this year.

Calving was expected to begin in late February, so Jacobsen “proactively deployed fox lights around the perimeter of the pasture to help serve as a deterrent measure.”

Fox lights, which were originally developed to deter foxes, are devices that flash random patterns of lights to simulate a human patrolling a field.

Fox lights are deployed around an active calving pasture to deter wolves from approaching cattle. Photo: WDFW

Elsewhere in the state, wildlife specialists have experimented with other nonlethal methods for scaring wolves away from livestock. For example, they have been testing radio-activated guard (RAG) boxes that detect the presence of collared wolves and haze the wolves with loud noises and a flashing strobe light.

RAG boxes also alert the livestock producer to a wolf’s presence.

That can be “an even bigger deterrent,” Spence said.

Another nonlethal deterrent is fladry—a braided metal wire mounted on fenceposts with fabric strips or flags that flap in the wind. “Turbo fladry” is similar, except the metal wire is electrified where that is an option.

Known as fladry, red flags fluttering in the wind can scare wolves. Some fladry, called turbo fladry, has an electric current running through it to shock wolves that try to cross it. Photo: WDFW

Another potential deterrence method uses guardian dogs to protect livestock.

No deterrence strategy is a silver bullet, and multiple strategies are used in some situations. RAG boxes, for example, work better for small, confined livestock operations than for protecting wide-ranging herds.

Washington is the only state that offers a program to share GPS location data from radio-collared wolves with qualifying livestock producers who agree not to share the data outside the program. The data can help ranchers proactively prevent conflicts between cattle and nearby wolves.

The program does not share data between April 1 and July 15, when wolves are most likely to be staying close to a den site with young pups.

Jacobsen said two ranchers in Klickitat County have enrolled in the program and signed annual agreements with the wildlife department.

Managing an endangered species

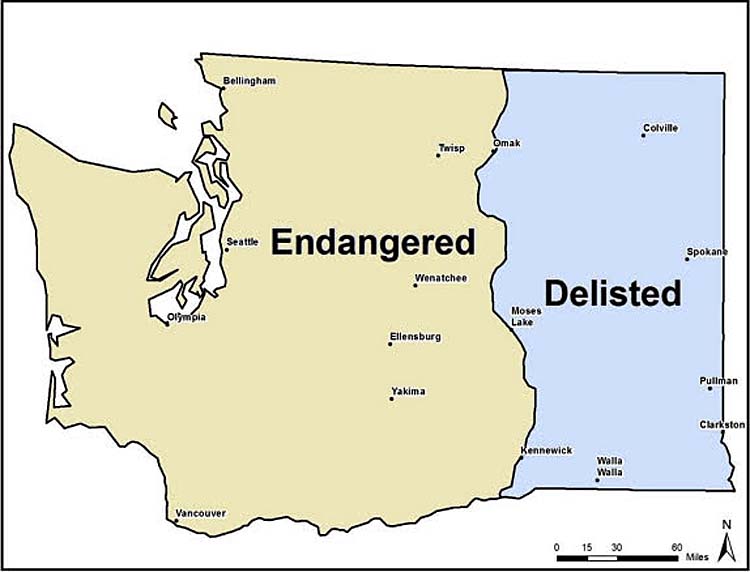

Wolves are currently listed as federally endangered in the western two-thirds of the state. That includes all of Klickitat County, and it means that the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has ultimate authority over wolf management in this region.

In the Eastern Washington recovery region, WDFW and tribal entities have the lead role.

Washington’s wolf plan anticipates full delisting of the species once there are at least four successful breeding pairs in each of the three recovery regions, and either three additional breeding pairs anywhere in the state for three consecutive years or six additional breeding pairs anywhere statewide for a single year.

The gray wolf is federally delisted in the Eastern Washington region but protected as a state-listed endangered species throughout Washington. Map: WDFW

Earlier this year, conservationists raised concerns about a bill in the state legislature, HB 1698, that would have given county officials more say in how wolves are managed. The bill had some conditions, but many viewed it as a move to replace federal and state management of wolves with local control.

The state wildlife agency did not back the bill, which stalled when it got to the House Appropriations Committee.

Opponents of the bill were especially worried about how it might be applied in Klickitat County, where Sheriff Bob Songer has run a controversial program using hound handlers to hunt cougars and other predators he deems a threat to public safety.

At a Klickitat County Board of County Commissioners meeting on Nov. 29, 2022, Songer told the commissioners that if wolves start chasing livestock, “they’re no different than a pack of dogs that are allowed by law to be shot … If you shoot one of those wolves, you call me and tell the game department the sheriff told you to shoot it.”

Songer also said it was his understanding that “the ones here [in Klickitat County] are not protected by the feds.” That is incorrect.

“What people should know about wolves in this area is that they’re federally protected and it’s illegal to shoot them,” Spence said.

Columbia Insight’s reporting on biodiversity in the Columbia River Gorge is supported by the Autzen Foundation and Pacific Power Foundation.

I believe the wildlife situation should be controlled by Fish and Game, not the Police dept.

We need to learn to live with wildlife. If they come into our civilized area ( which was theirs first) it should be emedintly reported to F&G so the animal can be tranquilized and taken back into the wilderness.

Last fall there was a bear that was in a yard eating apples, when the owner went outside to play ball with her dog

When the dog became uninterested in the ball and aware of the bear, the owner (not seeing the bear) called her dog to the house. When she turned on her porch, she finally noticed the bear, he was filling them. She freaked out and got her dog in the house. When the dog started barking (I imagine ,because the owner was overly anxious, tee beats rsn up a tree and stayed there. The owner called F&G, but for some reason they were on vacation this day. A few land owners wound this out and came to help. They made all kinds of noise to try to scare the bear down and away from the owners property. But the bear stayed in the tree. One of the locals had a bear tag and the bear was shot while up the tree. It took 3 men the pry the claws out of the tree to get the bear down, after being shot.

I realize this was in a town where people live. But it is obvious that the bear was just eating apples left on the ground by the owner. The bear could smell them and was filling up for winter. The bear should have been tranquilized and taken back up to the reservation. He did not try to attack, he was curious. In my opinion this was totally wrong. Authorities in the F&G should have been available. The sheriff’s office had advised the owner to kill it.

We forget and many think humans are the only thing that has a right to life. We have moved into their territory. We need to find ways to live with them, not exterminate them. Just my opinion.

Don’t publicize their whereabouts. Too many sickos out there!

We know where they are..you will be the first to know if you have calves, dogs, young baby elk, or sheep.

Cathy, spreading fear is so eighteenth century. Wolves will hunt elk and other ungulates when available. Ranchers who are not using non-lethal deterrents will have problems. The WDFW have been doing an excellent job in the last few years and I trust their good work will continue…and I agree with Elaine to not tell anyone where there are.

Hello Dawn – — I thought you might appreciate knowing that WA is not the only state that gives radio-collar data access to livestock owners. It is also done in the Southwestern U.S., in New Mexico and Arizona, and in those states the amount of illegal wolf-killing/poaching has been extremely high. In two of the few instances where the perpetrator was actually identified, arrested, prosecuted and convicted, it was livestock owners who had been given access by the agencies to wolf radio-collar data. If you’ve been following wolf recovery in Washington over the years, you must be aware there have been multiple illegal killings/poachings of wolves almost every year. The issue became greatly elevated when in 2022, at least 6 wolves were found illegally killed by poisoning in NE Washington. Scientists in both the U.S. and Europe have concluded that most poaching of wolves is cryptic, that is, undiscovered, and that for every wolf poached which is discovered, there are another 1-2 wolves that have been poached whose deaths will never be discovered. Which means that wolf poaching is actually 2-3 times higher than what agencies report to the public and agencies severely underrepport and fail to consider in their wolf management activities the actual level of illegal wolf killing taking place. Which, in turn, hampers recovery of the species. You will also notice that each year for the past six years, the percentage annual growth of Washington’s wolf population has been far below the 30% annual growth rate that is expected from a recovering wolf population in the early stages of recovery. This last year, the growth rate was only 5%. WDFW likes to tout that since 2008, when the first pack was confirmed, that the annual growth rate has “averaged” around 23-28%. They never acknowledge that in the years the agency has killed a lot of wolves, or in the years there have been a lot of discovered poaching, the annual growth is far, far below that rate. For instance, in 2018, the annual growth rate was only 3.27%, and in 2017 it was only 6%, and in all the other years from 2016 to the present, it has never been above 23% and has usually been far less. Given this year’s low growth rate and the high number of discovered wolf poachings, and looking at the experience in the Southwest, the practice by the agency of providing wolf location info as specific as actual radio-collar data is a practice that’s highly fraught and should be discontinued.

Hi Amaroq, thanks for that information about Arizona and New Mexico. I would like to learn more about those incidents involving poachers who were given access to location data.

Hi Amaroq, I looked into this a little more and learned that Washington’s program differs from data sharing in the Southwest in at least two ways. Washington provides livestock producers with higher-resolution data than the Mexican gray wolf program—actual GPS points on a map, rather than “coarse” data showing only the general area where wolves have been. Washington also shares the data more quickly with livestock producers, sometimes a matter of hours rather than weeks.

Dawn,

Thank you for the informative story. Amaroq Weiss correctly points out that the often cited 28% growth rate is misleading when evaluating recent population trends that are much lower. In addition, it is misleading that the Department includes in its state wolf population numbers the wolves living on tribal lands when they do not have full authority to manage these wolves. For example, the Coleville Tribe has killed (legally within their tribal rights) 33 wolves over the last two+ years or about 7% of the “state population” in 2022 and 2021. My point is that while recovery is underway it is important to maintain the state endangered status.

Why is the tribe killing so many wolves? I was hoping in Klickitat that the Yakama will be good stewards.

Hi Shelley, the gray wolf is federally delisted in the eastern 1/3 of Washington (see map above). As the Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation explain on their website (https://www.cct-fnw.com/gray-wolf/): “In areas where wolves become federally delisted, tribes can develop their own management plans and regulations that may not be consistent with the state wolf plan.” (The Spokane Tribe also manages wolves on its lands.) In the western 2/3 of the state, which includes all of Klickitat County and the Yakama Indian Reservation, wolves are still federally listed.

Good luck with Songer and his posse. Any phone call to his office about a wild predator near someone’s home and/or livestock will have the hounds showing up. I hope there is a solid plan on what to do when citizens do not comply with the state and federal laws on killing the wolves. There is a lot of trophy hunters here.

I want to see the wolves succeed, but I am also concerned that that it will be compromised.

Do you have documented proof that the Yakama Nation named the Big Muddy pack? There are enrolled Yakamas who are saying that is not true.

Hi Laurene, please see page 13 of the Washington Gray Wolf Conservation and Management 2022 Annual Report published by the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife on April 7. Near the bottom of the page you will find this: “A new pack, Big Muddy, named by the Yakama Nation Wildlife Resource Management Program, is the first pack to establish in the South Cascades and Northwest Coast recovery region.” You can download the report at https://wdfw.wa.gov/publications/02419

Why the Hell don’t ranchers use flock protecting breeds of dogs.

I never see that being used as a solution or addition to the problem.

Somehow the Middle East and other countries have been doing this

successfully for ever because it works.