The City of Trees Challenge aims to plant 100,000 trees as a response to worsening heat islands around the city

More leafy greens: A new program is adding color—and vitality—to Boise neighborhoods. Photo: Click Sluice/Unsplash

By Don Campbell. December 29, 2022. Summer in Idaho’s Treasure Valley can swelter.

This year it melted under the most 100-degree days on record, while 2021 sweated it out with the hottest temperatures ever logged in the region.

Ah, but for the shade of a tree.

While the world clamors about climate change, in 2020 Boise sprouted a cooperative grassroots program that’s working directly to spread a city- and statewide canopy of trees to help beat that egregious heat, improve air quality, even enrich mental health and well-being via the psychological benefits of vegetation.

The City of Trees Challenge is a coalition that brings together the City of Boise, Treasure Valley Canopy Network and Nature Conservancy Idaho to lead “a new movement for community recovery and climate resiliency.”

Broadly, the coalition hopes to rally the citizens of Boise over the ensuing decade to plant one tree for every household in the city—some 100,000 trees—while challenging the community to sponsor one seedling for every person citywide.

That’s approximately 235,000 forest trees to be planted across Idaho.

Importance of ‘city trees’

Multiple studies have shown that in cities a lack of tree canopy—coverage created by mature shade trees—is a factor in multiple socioeconomic problems.

Disadvantaged neighborhoods often have less canopy coverage, more paved surfaces and, thus, higher temperatures.

“Unequal distributions of tree abundance and diversity have also been shown in parts of the country to connect to racial, educational, age and income-based inequalities,” according to a recent Idaho Statesman article.

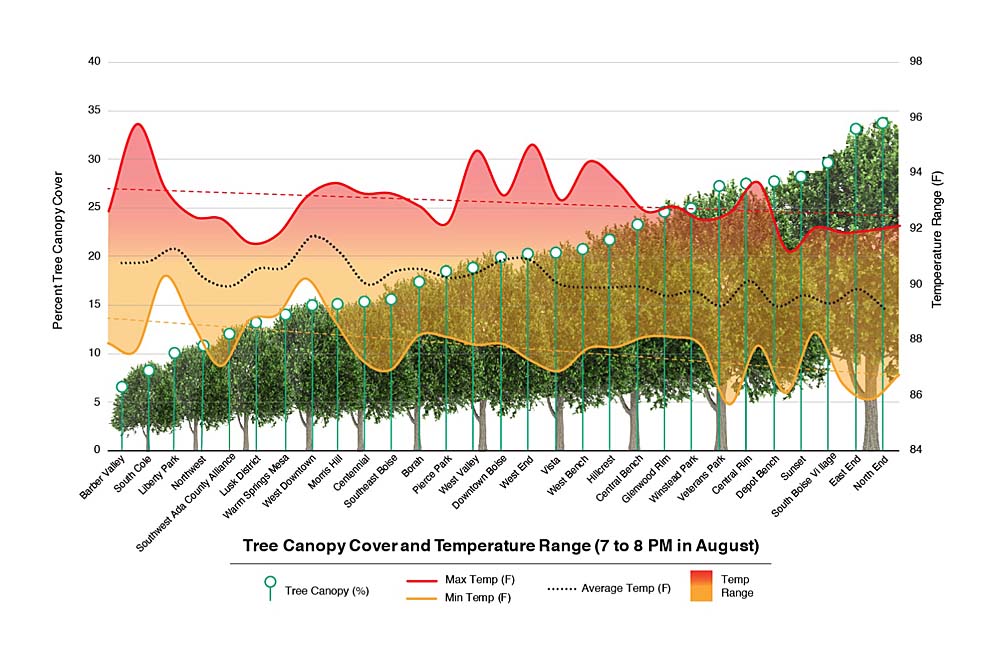

Tree canopy and urban heat: In summer, neighborhoods across Boise with the lowest tree canopy are much hotter than neighborhoods with higher tree canopy. Residents of these “heat islands” suffer health problems at higher rates. Infographic: City of Trees Challenge

Data that proves the benefit of trees in cities is mounting.

A recent U.S. Forest Service study found that “each tree planted in a community (is) associated with significant reductions in non-accidental and cardiovascular mortality among humans living nearby,” according to ScienceAlert.

The study concluded the yearly economic benefit of tree planting dramatically exceeds the cost of maintaining them, by a factor of more than 1,000.

Other studies have shown that access and exposure to “nature health”—not just wilderness but urban forests and tree-lined streets—can significantly benefit humans. Trees not only provide shade, but also reduce electricity use, cool sidewalks and streets and help keep air and water clean.

The Forest Service study relied on a “well-documented tree-planting campaign undertaken in Portland, Ore., between 1990 and 2019,” reported ScienceAlert. “During those three decades, the nonprofit group Friends of Trees planted 49,246 trees in Portland.”

Most importantly, the Portland group kept records of where and when each tree was planted. This enabled researchers to study the number of trees planted in specific neighborhoods or U.S. Census tracts.

Employing data from the Oregon Health Authority, they then associated each census tract’s tree data with the area’s mortality rate due to cardiovascular, respiratory or non-accidental causes.

“The results show that in neighborhoods in which more trees had been planted, mortality rates (deaths per 100,000 persons) were lower,” according to Phys.org, which reported on the study. “This negative association was significant for cardiovascular and non-accidental mortality (that is, all causes excluding accidents), particularly for males and people over the age of 65.”

Building a public-private coalition

On Arbor Day 2020, Boise City Council President Elaine Clegg helped launch the City of Trees Challenge with the goal of planting 100,000 trees over 10 years.

Though seed money was available from the city, Clegg believed a strong, civic partner would be essential for fundraising and empowering citizen action.

Branch manager: Elaine Clegg. Photo: City of Boise

She tapped the Treasure Valley Canopy Network (TVCN), a nonprofit that recognizes the value urban forests provide in building a livable community and which bases its activities on collaboration, innovation and sustainability.

The Nature Conservancy of Idaho was added as the third leg of the triumvirate.

Lance Davisson, founder and executive director of the TVCN, says the collaborative approach was vital not only to get the program off the ground, but to build awareness of the value of expanding Boise and the region’s tree canopy.

“We’ve built a really strong team,” says Davisson.

Danny Roop, a sustainability specialist with Boise’s Parks and Recreation Department, came aboard to represent the city’s interests.

“To take on something of this size and magnitude, it’s worked out well,” says Roop. “It’s been a hugely collaborative process across Boise and nationally.

“We get a lot of funding from the Arbor Day Foundation for our seedlings, and a lot of funding from the Forest Service. What Treasure Valley Canopy Network brings to the table is all of that collaboration. If we’d kept this as just a city program, there’s no way it would have all of the partners it does right now and wouldn’t be nearly as robust.”

Start strong, stay strong

In its first year, the Challenge gave away 500 seedlings at a Boise farmers market and earned much-needed publicity for its effort.

But it also ran the risk of fizzling after the initial shine dulled.

Root cause: Lance Davisson. Photo: Treasure Valley Canopy Network

“I’ve been doing this kind of work for 25 years,” says Davisson. “I’ve seen it in cities like New York and L.A. Politicians love to say, ‘We’re going to plant a millions trees. It’s going to be awesome.’ What usually happens is they get a splash in the paper for a year or two, sink a bunch of money into giving away free trees to people and they’re really not intentional about the right tree, the right place, the right size and truly engaging neighborhoods.”

What makes the Boise program different?

“Elaine (Clegg) is brilliant,” says Davisson. “She knows that number (100,000 trees) means something to people. With all that I’ve learned about the people who messed it up, and all that I’ve learned about the people who’ve done it well, I knew we could do it right.”

Davisson says Clegg has been the right person to make a splash because she works to bridge what seems to be an ever-present urban-rural divide.

By empowering homeowners and neighborhood groups, the program has generated significant vitality.

Volunteer planters

A major success in 2022 has been the Boise Tree Captains program, a citizen push to drive the effort as volunteers—many from the Boise Farmers Market and TVCN’s network.

“They already knew how to talk to their neighbors,” says Davisson. “And they got 165 trees planted in locations where we needed them the most. They made connections with the homeowners so the homeowners take care of them.”

The project works both as an urban opportunity as well as a state forestry project, in conjunction with the Forest Service.

Urban seedlings come largely out of Oregon and are made available through a local Boise nursery.

The Forest Service provides seedlings for the public forest segment, with the City of Trees Challenge providing some funding.

Now that this seed of an idea has found purchase, the collaborative effort will push it forward.

“We have some runway,” says Davisson. “We’re leaps and bounds ahead but also behind. Forest seedling will meet its goal in two years. The 100,000 (urban) trees—we have a long way to go.”

As of this writing, the project has planted 13,776 urban trees and 149,000 forest seedlings.

The Challenge needs more funding to add staff.

“We have a strong team, but we need to double our efforts,” says Davisson. “We need to plan, we need to plant and we need to grow these trees.”

New numbers

Gathering more data is crucial.

TVCN got its start from a 2011 tree-canopy study commissioned by the State of Idaho and the Forest Service and executed by Portland State University.

The study has been a valuable resource. But it’s now out of date.

“We always knew the 2011 data needs to be updated,” says Davisson. “One of the key pieces is having the right data to inform what we do strategically.”

The City of Trees Challenge has invested in an update to that 2011 tree canopy assessment.

“We’re about to execute a contract with a company called AppGeo, which will come in and do an update of that 2011 data,” says Davisson.

That update will mean being able to compare progress over 10-plus years and create tools using new data to map out the next 10 years.

“There are so many pieces to the puzzle,” says Davisson. “What we’ve done well is when we’re planning and budgeting, we’re not just planning and budgeting for trees. As we build and grow, we’re making an effort to make sure we have the right data.”

Spreading the canopy

While City of Trees Challenge has drawn on other regions’ concepts and practices—including Root Nashville, another successful private-public initiative whose goal is to plant 500,000 trees by 2050—the Boise effort hopes its model spreads.

“We’ve begged and borrowed from a lot of folks,” says Davisson. “One thing I like about urban forestry nationally is that most people like other people to steal their ideas.

“We want people to replicate what we’re doing. We’re not doing anything earth-shattering, but I do think we’re doing it better than most.”

Will Boise hit that 100,000-tree mark?

“I’ve come to realize that numbers don’t matter so much as the action that we’re taking,” says Roop.

“What I don’t want to see is 20 years from now is, ‘It was cool! They planted 100,000 trees,’ but we don’t know where they’re at, we don’t know if they’re making a difference,” says Davisson. “I’d rather they said, ‘It’s amazing. They planted 70,000 trees, they didn’t meet the 100,000 mark, but look at what those trees did.’”

Don Campbell is a Pacific Northwest writer who currently lives in Mosier, Oregon.

RELATED: Pac NW’s ‘trees of life’ are dying. Now we know why

RELATED: Money now growing trees

Trees can make a big difference, but BIG trees make a much bigger difference. Making this effort successful will require a re-thinking on the part of city and county planners. Narrow planting strips, combined with smaller lot sizes, make large trees almost impossible to grow, or can cause damage to streets, sidewalks, foundations, and roofs. Planting strips next to streets need to be at least 12 feet wide, and preferably 15, to accommodate large, useful, long lived trees. Smaller lot sizes are likely a fact of life we will not change, but planting a large tree less than 30-40 feet from your house may require its removal or severe trimming just as it reaches a size where the shade and photosynthesis advantages start becoming effective.