The U.S. Army’s Yakima Training Center contaminated scores of private wells, but it’s resisting providing assistance to all those affected

Cleanup controversy: Firefighters extinguish a helicopter fire during a 2007 training exercise at Yakima Training Center. Local residents are still dealing with the mess. Photo: U.S. Army

By Andrew Engelson. December 5, 2022. A U.S. Army training center outside Yakima that contaminated multiple private wells with PFAS—so-called “forever chemicals”—is at the center of a looming legal battle over the definition of safe levels of toxins.

And who should pay to fix the problem.

On Nov. 30, the Washington Department of Ecology sent a letter the U.S. Army, giving it 14 days to respond to a previously proposed cleanup agreement.

If the Army refuses to respond or comply with the agreement, Ecology will then issue an enforcement order, the first step in legal action against the Army.

At issue are toxins that entered ground water and drinking supplies at the Yakima Training Center—what the Army calls “the military’s premier training destination in the Pacific Northwest”— near Selah, Wash.

In the 1980s and early 1990s, the Army practiced putting out aircraft and helicopter fires there by digging trenches, filling them with fuel and setting them on fire.

The fires were put out with firefighting foam containing PFAS. Eventually, those chemicals seeped into ground water.

No public water systems were affected, but private wells were.

As reported this year in the Yakima Herald and the Seattle Times, in the summer of 2021 the Yakima Training Center began offering to test private wells in areas surrounding the center.

According to Greg Caron, regional manager for hazardous waste at the Washington State Department of Ecology, the Army has sampled about 300 wells and found that 62 wells serving 87 households are above what the Army considers safe limit for PFAS: 70 parts per trillion, set by the EPA in 2016.

Room to move: The 327,000-acre Yakima Training Center consists of 25 ranges that allow service members to train collectively or individually. Photo: U.S. Army

Complicating matters is that in 2021 the Washington State Department of Health set recommended limits in drinking water to 25 parts per trillion for two of the most common PFAS compounds: PFOA and PFOS.

“So, when your well water or your drinking water exceeds 25 parts per trillion for those two compounds,” Caron says, “Washington State Department of Health advises you to take measures to reduce your exposure by drinking bottled water, finding an alternative water source or installing treatment.”

Further adding to the confusion, in June 2022 the EPA lowered its PFAS advisory levels drastically— to four parts per quadrillion for PFOA and 20 parts per quadrillion for PFOS.

This effectively means if any PFAS chemicals are found, the EPA recommends taking action.

“The new levels are so low they’re actually below what we can detect in drinking water,” says Barbara Morrissey, a toxicologist with the Washington State Department of Health.

Caron says the Army decided to stick with the 70 parts per trillion level. It has agreed to provide bottled drinking water to households exceeding that standard.

But for the 30 or so additional households that don’t meet the state level, the Army hasn’t agreed to help out.

If Ecology issues an enforcement order, which outlines violations of the state’s Hazardous Waste Management Act, it will then outline proposed actions the Army needs to take to be in compliance.

“Then, the Army could do one of two things,” says Caron. “They could then come to the table and talk to us about what they’re willing to do. Or they could simply ignore it. That would mean Ecology would have to go to state or federal court to enforce that order.”

The U.S. Army did not respond to multiple interview requests from Columbia Insight.

What are PFAS chemicals?

“It’s everywhere. Quite literally everywhere. Everybody has it in their homes. Everybody has their blood. It’s in every single landfill, every single wastewater treatment plant.”

That’s how Brian Pinkard describes PFAS, a class of persistent and widespread toxic substances. Pinkard is the co-founder of Aquagga, a Tacoma company that hopes to remove these chemicals from the environment.

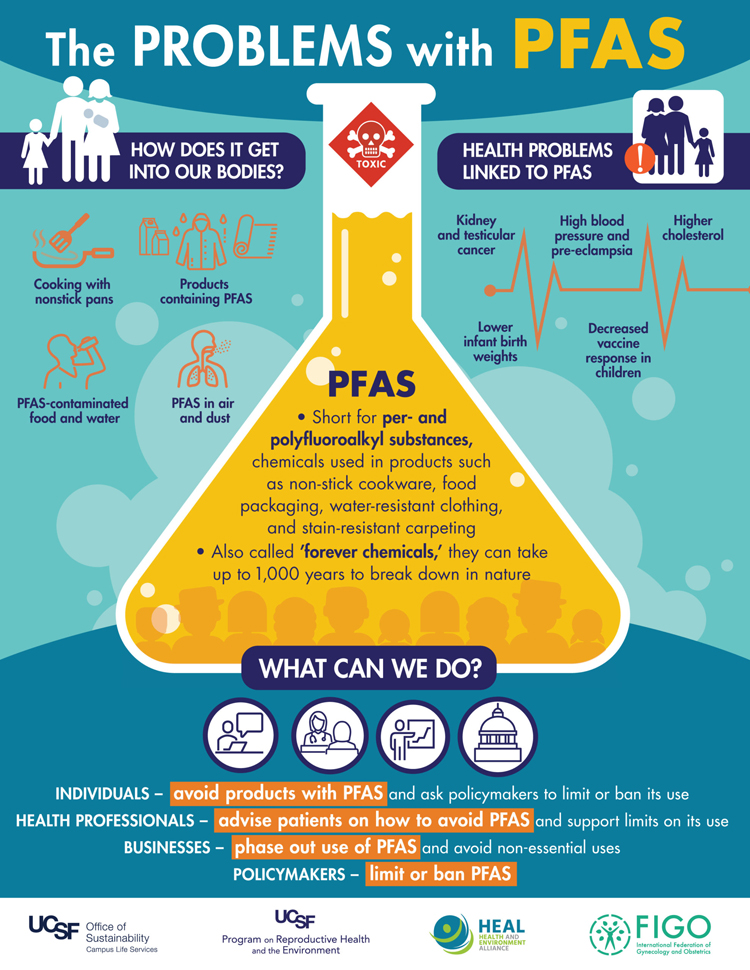

PFAS—short for per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances—are found in more than 5,000 substances. Long used in food packaging, waterproof products, nonstick pans, carpets and firefighting foam, PFAS chemicals are found in the blood of 97% of Americans —though levels have been declining since some products containing PFAS were phased out in the early 2000s.

Infographic: Health and Environment Alliance

Because PFAS don’t degrade in nature, these “forever chemicals” can be a major problem, especially when they show up in drinking water.

According to the Washington State Department of Health, long-term exposure to PFAS has been connected to a range of health problems, including decreased birth weight, lower immune response to vaccines, higher cholesterol, liver damage, higher risk of thyroid disease and increased risk of testicular and kidney cancers.

“We’re still learning about PFAS,” says Morrissey. “We can’t say for sure exactly what the risks are. But we have enough evidence to be cautious and to take action to reduce people’s exposure.”

Army “essentially ignoring” state

During past chemical spill cleanups at the Yakima Training Center, Caron says the Army and local base commanders cooperated with the Department of Ecology.

This hasn’t been the case with PFAS.

Explosive area: Out-of-date ammunition disposal at the Yakima Training Center firing range site. Photo: Wash. Dept. Ecology

The Pentagon has taken the Yakima Training Center PFAS investigation away from local officers, says Caron.

“When PFAS was discovered, the Army’s environmental command took control of the investigation,” says Caron. “They’ve been making their decisions about what to do and when—without any input from the state. The Army’s essentially ignoring us.

“Part of my agency’s responsibilities are we can make the polluters pay. We can go to those responsible for the contamination and make them pay for the impacts and to clean it up.”

The Nov. 30 letter that Ecology sent to the Army is the first step toward legally compelling the Department of Defense to pay to clean up PFAS near the Yakima site.

Morrissey says that because the Yakima Training Center isn’t an existing Superfund site, neither the Department of Ecology nor the EPA has the legal authority to compel the Army to do anything.

“That’s frustrating, because we’d like to see somebody have that oversight role,” she says.

Additionally, the EPA has so far only issued non-binding health advisories regarding PFAS, but is currently in the process of evaluating whether to designate PFOS and PFOA as hazardous substances covered by CERCLA (Superfund) legislation.

Other contamination sites in Washington

In Washington state, four other major PFOS contamination sites have been discovered since 2016: near Whidbey Island Naval Air Station , Fairchild Air Force Base outside Spokane, Joint Base Lewis McChord near Tacoma, and the city of Issaquah, near the site of a firefighting training center.

At Whidbey Island, the Navy agreed to provide drinking water to households over the 70 parts per million threshold.

At Fairchild, the city of Airway Heights shifted some of its supply to Spokane, and installed a filtration system.

At Joint Base Lewis McChord, the Army found levels at 16.4 parts per trillion and took no action.

The City of Issaquah installed a filtration system in 2016 to eliminate PFAS from its drinking water supply.

Morrissey says that prior to the state and EPA setting lower limits for PFAS, the process for these sites was more straightforward.

“Things were different then. We didn’t have our state action levels at that point,” she says.

Competition to eliminate PFAS

Meanwhile, at the University of Washington in Seattle, a researcher and his team have successfully created and tested a device that can break down PFAS, no longer making them “forever chemicals.”

In a study published in September in the Chemical Engineering Journal, associate professor Igor Novosselov in UW’s mechanical engineering department described a process in which PFAS can be broken down using “supercritical water.”

When exposed to pressure 200 times that found at sea level and at temperatures between 400 and 650 degrees Celsius, water is in a plasma state that’s neither a liquid nor vapor.

Novossolev’s team found that PFOS and PFOA were destroyed in this plasma in a matter of just 30 seconds.

“There’s no question about it,” Novossolev says of his results. “We’ve been operating this thing for thousands of hours.”

The trick, however, will be to pull PFAS chemicals from soil or ground water in high enough concentrations to use this process to destroy them.

[perfectpullquote align=”full” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]A handful of competing technologies are being developed to get rid of PFAS.[/perfectpullquote]

Novossolev says there are existing technologies, such as membrane processes and reverse osmosis, that can concentrate PFAS to levels at one part per thousand, which would make destruction viable on a large scale.

“That’s where we come in,” he says. “We see ourselves as an end-of-line technology that will basically destroy this very contaminated waste stream.”

In Tacoma, Aquagga hopes to utilize a similar technology to destroy PFAS.

Founded in 2020 by Brian Pinkard, a former student of Novosselev’s, Aquagga is working on implementing a technology developed at the Colorado School of Mines.

Pinkard says it’s similar to the process developed at UW, but operates at slightly lower temperatures, and adds sodium hydroxide to the mix in order to break down PFOS and PFOA.

“We’ve built a system that processes a gallon per hour of concentrated liquid PFAS wastes,” Pinkard says. “It’s about the size of two refrigerators. We know that the process works really well.”

Pinkard says there are currently four or five competing technologies being developed to get rid of PFAS. He says each may fill a particular niche, “whether you have contaminated soil or contaminated groundwater or a stockpile of firefighting foams that need to be disposed of.”

He estimates that once the EPA sets enforceable limits, in the next three years or so, major cleanup contracts will be awarded.

Residents await assistance

In the meantime, households near the Yakima Training Center that haven’t qualified to receive drinking water or filtration systems hope they’ll get assistance soon.

Morrissey says the Department of Health may seek funding from the legislature that would make grants available to private well owners who are affected.

Currently, most of these funds are only available to large, public water systems.

“Private wells don’t have any access to that at this point. So we’re looking to see if there are any options for financial assistance,” says Morrissey.