Adopted in 1973, the state’s unique land-use system was a reaction to postwar development, but it’s never stopped facing challenges

State champion: Oregon Gov. Tom McCall envisioned a balance between development and scenic spaces. Photo illustration: Nicole Wilkinson

By Carl Abbott, September 22, 2022. When Oregon Gov. Tom McCall famously warned the Oregon legislature in January 1973 about the “shameless threat to our environment and to the whole quality of life—unfettered despoiling of the land,” he spoke for many of his constituents.

He lambasted “sagebrush subdivisions, coastal condomania and the ravenous rampage of suburbia” as the doing of “grasping wastrels of the land.”

Half a century later, McCall’s speech keynotes the origin story of Oregon’s unique land use planning system.

But memorable phrases tell only part of the history of this landmark of Oregon policy.

In 1973, the governor was addressing a state that was already primed for action.

In the years following World War II, suburban growth began consuming Willamette Valley farmland. Increasingly affluent families were snapping up vacation properties with mountain and ocean views.

Oregonians in the latter half of the 1960s responded with conferences, reports and finger-wagging at the bad example of California.

In 1969, the legislature acted with Senate Bill 10. The legislation established land-use regulation as a state concern, requiring local governments to develop land-use plans in line with 10 statewide goals.

The intention was good, but the measure lacked teeth for monitoring and enforcement.

McCall promised to fix the problems when he ran for reelection in 1972.

Creating the Oregon land-use planning system

Adopted in 1973, Senate Bill 100 filled the gaps left by Senate Bill 10.

Crucially, it created a Land Conservation and Development Commission (LCDC) with the mandate to write revised land-use goals; and a Department of Land Conservation and Development to ensure compliance.

Counties and municipalities would study the goals and write plans that the new state agency would review, acknowledge as satisfactory or send back for more work.

SB 100 was conceived by and for the Willamette Valley.

A chief mover was Hector Macpherson, a Linn County dairy farmer concerned about protecting agriculture from urban sprawl. Oregonians need only to drive I-5 to realize that the rich valley between the Cascades and the Coast Range is a small garden within the vastness of the North American West.

The bill passed both houses of the legislature by comfortable margins. Forty-nine out of 60 legislators from Willamette Valley districts voted in favor, but only nine of their 30 colleagues from coastal and eastern counties agreed.

The disparity highlighted conflicting opinions about land use in the state that prevail to this day.

Making it work

Senate Bill 100 worked, but not simply because new legislation had been passed.

New laws need to be implemented through regulations and rules, judicial opinions, government agencies and citizen buy-in.

There are at least half a dozen reasons why the Oregon land-use planning system survived its early years and has become embedded in the way Oregonians do business.

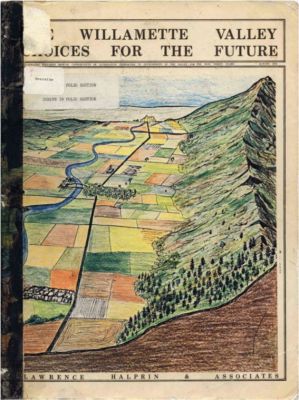

A 1972 report produced by landscape architects Lawrence Helprin and Associates helped crystallize opinion that without stronger land-use regulations the Willamette Valley would turn into Southern California.

Bipartisan support: Hector MacPherson and Tom McCall were Republicans, but the legislation got strong support from urban Democrats such as Ted Hallock of Portland and Nancy Fadeley of Eugene. A decade later, Republican Stafford Hansell, a farmer from Hermiston, led a review committee that started out skeptical and ended up supportive.

Thoughtful language: The wording and content of the 14 statewide goals incorporated community input that DLCD director Arnold Cogan gathered through dozens of workshops and hearings in all corners of the state. Language also counts: DLCD doesn’t approve or reject local plans, it “acknowledges” them, sometimes after several rounds of review.

Oversight: McCall helped to establish 1000 Friends of Oregon, a watchdog organization of energetic young lawyers who litigated key cases that made it clear that localities can’t skirt the requirements of the goals. In the ensuing decades 1000 Friends has continued to keep alert to questionable land-use decisions.

Urban Growth Boundaries: The single biggest early test of the policy was drawing the Urban Growth Boundary (UGB) for the Portland region. The Portland UGB is the most prominent single manifestation of the SB 100 system, the aspect that people outside the state are most likely to know about. The work of establishing the UGB went remarkably smoothly for a decision with great consequences for the value of land inside and outside the boundary.

Appeals process: The legislature fine-tuned the system by creating a Land Use Board of Appeals to relieve local courts and bring special expertise to zoning and land use disputes. It also tried to blunt potential opposition by developing alternative procedures for deciding the location of controversial public facilities such as prisons.

Balance: “Development” is built into the system along with “land conservation.” The Oregon system is a framework for orderly and efficient growth that minimizes impacts on productive farm and forestland. Urban Growth Boundaries around metropolitan areas and municipalities are supposed to include a 20-year supply of developable residential and industrial land and to be expanded as needed—think of a UGB as a skin that encloses a city but expands as it grows. There’s plenty of disagreement over the right balance of conservation and development, but it is an intended tension.

Ballot box challenges

In the 1970s and early 1980s, the statewide approach to planning survived four ballot measures.

Voters had rejected an early challenge to SB 10 in 1970.

The strengthened system created by SB 100 won 57% approval in 1976 and 61% approval in 1978. Support was strongest in Portland, Salem and Eugene, but also grew along the northern coast and in south-central counties experiencing rapid recreational development.

During the depression of 1981-82, however, complaints grew that planning requirements inhibited economic development. Voters in 1982 got to decide whether to abolish the LCDC and return all land-use planning authority to localities, with state goals purely as guidelines (in effect a return to SB 10).

Enduring balance: Oregon’s land-use policies have withstood numerous challenges. Photo illustration: Nicole Wilkinson

The returns showed the same regional divisions as before, with strongest opposition from ranching and lumbering counties. But the effort to abolish the LDDC failed.

The political scene was quiet until the emergence of a strong property rights movement at the start of the new century. In November 2000, 53% of Oregon voters approved Measure 7, an amendment to the state constitution that required government compensation for any and all loss of potential property value because of state or local land-use regulations (making it the nation’s most stringent property rights measure).

Non-metropolitan areas voted heavily for the measure, but it also picked up substantial support in Portland suburbs.

Measure 7 never went into effect because the Oregon Supreme Court disallowed it on the technical grounds that it simultaneously amended more than one clause of the constitution.

Property rights activists countered the court’s decision with Measure 37, this time as simple legislation. It passed overwhelmingly in November 2004.

Measure 37 required local governments, on request of a property owner, to waive regulations imposed since the most recent transfer of ownership or pay compensation for lost value.

Many property owners submitted modest claims to create one or two building lots, but some saw the opportunity for massive development.

Union County found itself with the possibility of a massive development in the middle of the Grande Ronde Valley. Measure 37 claims covered a whopping 2,300 acres of Hood River County, mostly on land zoned for exclusive farm use.

As Oregonians increasingly realized the full implication of Measure 37, the legislature placed Measure 49 on the November 2007 ballot to roll back the most extreme effects.

This time voters liked the compromise that vested some individual property rights while blocking massive subdivisions on farm and forestland.

The future of land use in Oregon

As we approach the 50th anniversary of SB100, the state land-use system is still visionary … and well-embedded in the apparatus of state and local government.

When the legislature passed SB 100, the primary goal was to protect farms and forests. Compact urban development was secondary, valued as a tool for maintaining the natural resource economy.

Over the decades the urban provisions have been increasingly important in themselves. Urban growth boundaries don’t stop land development, but they ensure that it’s more measured and thoughtful than in many states, curbing leapfrog subdivisions and second homes scattered in forests and farmlands.

[perfectpullquote align=”full” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]Conflicting opinions about land use in the state prevail to this day.[/perfectpullquote]

Looking forward, the Oregon planning system will be more valuable than ever as one of the state’s strongest tools for responding to our climate emergency.

Because it was developed during the energy crisis of the 1970s, efficient transportation has been an important goal from the beginning. Compact suburban and urban development are essential for supporting public transit and promoting communities where people can walk and bike in preference to using automobiles for short and mid-length journeys.

UGBs encourage infill, and changing patterns of retailing and office work make this even more likely in the 2020s. E-commerce is stranding overbuilt malls and leaving derelict big box stores with empty parking lots.

The popularity of working from home portends vacant office parks.

Such underutilized and sometimes abandoned real estate will offer sites for housing, schools and public facilities that also support energy efficient development.

Residents of the Columbia River Basin are painfully aware that warming climate turns forests and grasslands to tinder and makes it essential to limit the penetration of development into wildlands.

Oregon’s urban growth boundaries and restrictions on development in farm and forestlands are powerful tools to mitigate residential home sprawl.

They’re not sufficient when fires reach the magnitude of 2020 in Oregon, but they can mitigate some of the most egregious problems of the urban-wildland interface that’s become an intractable problem in other western states.

Carl Abbott is emeritus professor of urban studies and planning at Portland State University. He’s the author of many articles and books, including How Cities Won the West: Four Centuries of Urban Change in Western North America.

Great article that succinctly and clearly gives the background and history of Oregon’s land use planning system. The article brings the story forward into todays’ issues and pressures. We need land use planning that protects farms, forests, wildlife, fish, streams and our way of life more than ever as climate change puts pressure on natural and social systems. Having compact communities is good not only the environment but the economy.

Good job Carl!

Thank you! I fear Oregon’s land use planning system is on the chopping block. Too many legislators have little knowledge of this history. Developers are screaming for more land for “affordable housing”. The new governor will play a crucial role.

Get rid of SB 100