As demand for renewable energy grows, so does opposition to the massive facilities that generate it. “Distributed generation” could alleviate the strain

Moving the river: That’s a lot of stuff just to turn on a light. Can we do with less? Photo: Smart Energy International/CC

By John Harrison, August 4, 2022. Electricity used to be so simple.

Flip a switch and the lights came on. Most of us didn’t know where our power came from and didn’t really care.

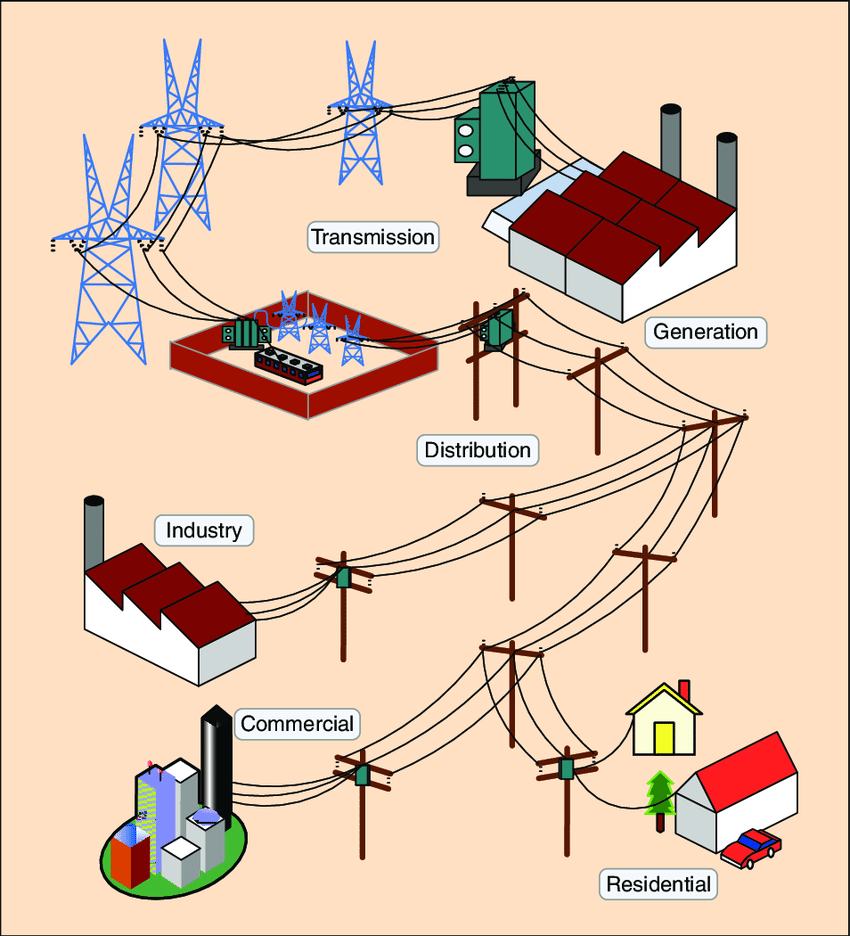

If we thought about it at all, we knew there were some huge power plants—hydropower dams, thermal plants fueled by coal or natural gas—connected to huge, high-voltage transmission lines that carried huge amounts of electricity to huge transformers, connected to smaller transformers, connected to wires that were connected to our homes.

Mostly out of sight. Mostly out of mind.

Today, most western states have adopted clean-energy policies, and the wholesale power market increasingly is dominated by emission-free, cheap renewable power.

Aging and economically inefficient thermal power plants (coal, mainly) are being retired.

As power consumers we can’t help but notice that if we don’t take actions—individual as well as societal—to reduce carbon emissions from power plants, vehicles and other sources, we face the very real possibility of a catastrophically warm future.

We are becoming—we have to become—more involved in our personal energy use and society’s energy future.

We no longer can afford to be passive consumers. For our own welfare—economic, societal—we’re becoming better informed energy consumers.

View point: Pretty cool. But what if they were in your backyard? Photo: Sam Churchill/CC

Supply-side resources are evolving rapidly, trending away from thermal power plants to carbon-free renewables in response to concern about global warming and to comply with state clean-energy policies.

Demand-side resources are evolving, too, and rapidly.

Energy efficiency—aka “conservation”—has been the principal demand-side resource in the Pacific Northwest for the last 40 years, helping our region reduce its demand for power by using it more efficiently.

But as demand for renewable energy increases and the technology that creates it improves, a new problem has arisen—where to locate new and needed massive power-generating facilities?

Concerns are being raised about industrial-scale solar and wind farms blocking wildlife corridors, harming birds, ruining scenic views, infringing on tribal lands and being installed in rural communities whether the locals like it or not.

How will we balance the need for renewable energy on a mass scale with the problems increasingly associated with industrial-scale facilities?

New term to learn

The most exciting developments that can be seen as at least a partial solution are with what are called “distributed generation resources.”

The most common “distributed generation resources” are the rooftop solar panels that all of us have seen on private residencies or commercial buildings, and some of us own.

These small-scale, location-specific devices can supplement or even replace a connection to a local electricity distribution service, such as a public utility.

[perfectpullquote align=”full” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]About 16,600 Portland General Electric customers have rooftop solar installations. Growth in 2021 was 20% greater than in 2020.[/perfectpullquote]

The idea is that as consumers take ownership of their own power generation, the cord is cut—or at least weakened—between users and large-scale power suppliers located hundreds of miles away.

“Distributed generation resources” theoretically lessen the need to transport power across the countryside via power lines and towers.

Create enough small distributed generation sites and you’ll need fewer utility-scale installations disrupting the landscape. Or so goes the thinking.

Interest surging

Perhaps the most exciting and practical of the evolving, carbon-free, demand-side technologies is energy storage, i.e., batteries.

In its 2021 Integrated Resource Plan (IRP), PacifiCorp, which includes Pacific Power based in Portland and Rocky Mountain Power based in Salt Lake City, noted that customer interest in self-generation is growing—solar alone and solar plus battery backup.

Living the dream: Residential solar-power generation isn’t news in the Dutch city of Amersfoort. Photo: Eneco Group

Pacific Power is seeing a surge of interest in solar. As of June 7, the utility had 12,065 net-metering customers (10,897 are residential), with 90% of those self-generating solar power.

Installations are increasing in 2022. Through late May, Pacific Power says it had put in 345 new net meters, compared with 180 by the same time in 2021, 110 in 2020 and 70 in 2019.

Batteries also are becoming more common.

“In 2018, we only had 14 batteries installed,” says Tim Gauntt, a Pacific Power spokesman. “This bumped to 23 in 2019, 52 in 2020, 63 in 2021 and we have had 39 in 2022 so far with 94 installations pending approval.”

Portland’s other electric utility, Portland General Electric (PGE), is also tracking increases in distributed generation resources.

Sarah Hamaker, a PGE spokesperson, says approximately 16,600 customers have rooftop solar installations, and more than 90% of these are residential systems. The number is rising—growth in 2021 was 20% greater than in 2020.

PGE also contracts for other demand-side generation, including small-scale wind and hydropower, fuel cells, biogas generators and some combined heat and power generators. This technology produces electricity with a thermal fuel such as natural gas, but also provides heat from this combustion.

Costs on both sides inhibit growth

All this is good news for consumers, but it might be not-so-good news for utilities.

As solar installations increase, some utilities are growing concerned about the cost of paying customers for the power they generate and return to the grid, and whether those payments amount to a subsidy that disadvantages other customers.

Idaho Power Company recently announced it was considering a ”transition” to a revised net-metering rate.

The current “export credit rate” is between 8 and 10 cents per kilowatt-hour. But in a study submitted to the Idaho Public Utilities Commission, Idaho Power proposed alternative methods for calculating the export rate that would reduce it to less than 4 cents per kilowatt-hour.

The proposal drew criticism from environmental and consumer groups. The Sierra Club called for an independent review of the study; the Idaho Conservation League said cutting the export rate in half would effectively make rooftop and other small-scale solar installations “financially unavailable” for many homeowners and businesses.

Portland General Electric compensates solar exports “at the applicable retail rate, which is currently just over 12 cents per kilowatt-hour for residential customers,” according to Hamaker.

That rate may be adjusted in the future by the Oregon Public Utilities Commission, she says.

Going our way? Most consumers take energy from the grid. A few send it back. Photo: BPA

Cost also is an issue for consumers. While the cost of home solar installation has come down over time, and probably will continue to decline, it still isn’t cheap.

According to Energysage—an “unbiased solar matchmaker, connecting homeowners with our network of over 500 pre-screened solar installers”—the cost of a home solar installation in Oregon in 2022 is between $11,475 and $15,525.

Energysage says the payback period for a 5,000-watt system in Oregon is 9.9 to 13.3 years, and that the net energy savings over 20 years would be between $14,565 and $19,705.

While costs are substantial for many homeowners, solar installations are nonetheless booming.

According to the Oregon Department of Energy, the total amount of solar generation in Oregon—residential, commercial, utility-scale—grew more than five-fold between 2015 and 2019, with generation increasing from 116,000 megawatt-hours to 776,000 megawatt-hours.

However, most of the growth came from utility-scale solar. In 2018, utility-scale solar accounted for 79% of solar generation in Oregon, with commercial solar accounting for 13% and residential solar accounting for 8%.

As of 2019, there were about 18,000 residential and commercial solar facilities in Oregon, and 77 utility-scale solar farms.

The problem with low energy costs

Solar’s increase is evident throughout the Pacific Northwest.

According to the Northwest Power and Conservation Council, rooftop solar installations are expected to increase in the four-state region by about 10% per year through 2050.

As of 2020, behind-the-meter solar (it’s not always installed on roofs) totaled 538 megawatts of installed capacity in the Northwest.

Ten percent per year isn’t a rapid growth rate. There’s a reason for that, says Massoud Jourabchi, the Council’s manager of economic analysis.

Because of low electricity prices in the Pacific Northwest compared with the rest of the nation—Southern California, for example, where the average cost of electricity is twice what it is in the Northwest—installing solar panels with battery backup isn’t economical for many consumers.

Holding the line: The traditional power grid is increasingly antiquated. But, in the Northwest, comparatively affordable. Image: Xinghuo Yu/ResearchGate

Jourabchi suspects people installing solar panels or panels plus battery backup devices probably aren’t motivated by cost, but by personal interest—doing something good for society by using less electricity generated with carbon fuels, or an interest in greater personal energy independence.

“My opinion on the demand side is that more is needed desperately, but we don’t quite have the market construct and regulatory processes to support a robust demand side yet,” says Nicole Hughes, executive director of Renewable Northwest.

One way around the cost issue is a “community” renewable energy project. These are becoming popular in Oregon.

Community systems have the advantage of economy of scale—a small group of consumers can participate in a community distributed generation project for less individually than installing their own equipment.

A typical minimum consumer investment might be as low as $1,000.

Rebates remain important incentive

In light of state-mandated lower emissions goals, Oregon utilities are encouraging customers to look into home energy generation.

They’re helping customers interested in a home solar installation navigate the maze of incentives, rebates and tax breaks that can greatly reduce the cost of a system.

Rebates are important both for solar installations and for other demand-side products, like electric vehicle chargers.

In June, Pacific Power announced a new set of rebates for installation of rapid (Level Two) electric-vehicle chargers in homes and workplaces.

The program offers a rebate of up to $500, capped at 75% of total project costs, which can include the charging equipment, permits and electrical installation work. For income-qualifying homeowners, the rebate can be as high as $1,000.

People power

Energy experts are generally optimistic that the market will evolve, costs will come down, technologies will improve and a zero-carbon electric energy future is realistic.

Electricity isn’t so simple anymore. With distributed generation resources we can participate in our power system.

We might never be completely rid of fossil fuels, but now that we recognize greenhouse gas emissions as the root of climate change, we have the ability to do more than just flip a switch and walk away.

We have the ability to do something about it.

The Fred W. Fields Fund of Oregon Community Foundation supported this story.