Plastic garbage isn’t just an ocean problem. Microplastics from clothes and other domestic sources are proliferating in the Columbia and Snake Rivers

A river runs to it: Plastic fragments collected on along 75 feet of Oregon Coast at Cape Perpetua. Photo: Wolfram Burner/CC

By Charles Coxe. January 6, 2022. The relentless buildup of plastic waste in our oceans is a well known crisis. Viable solutions for small and large collections of oceangoing plastics, such as the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, remain elusive.

But the primary source of these huge gyres is relatively un-studied, and just as insidious: microplastics in our rivers.

New research is showing that while microplastics in rivers inevitably dump into oceans, they cause a lot of freshwater problems along the way.

In a December webinar presented by Columbia Riverkeeper, Kirsten Kapp, professor of biological sciences and math at Central Wyoming College, walked through her pioneering research on microplastic pollution in freshwater ecosystems.

“Most of us think microplastics are an ocean problem,” said Kapp. “That’s simply not the case.”

Microplastics in Snake and Columbia

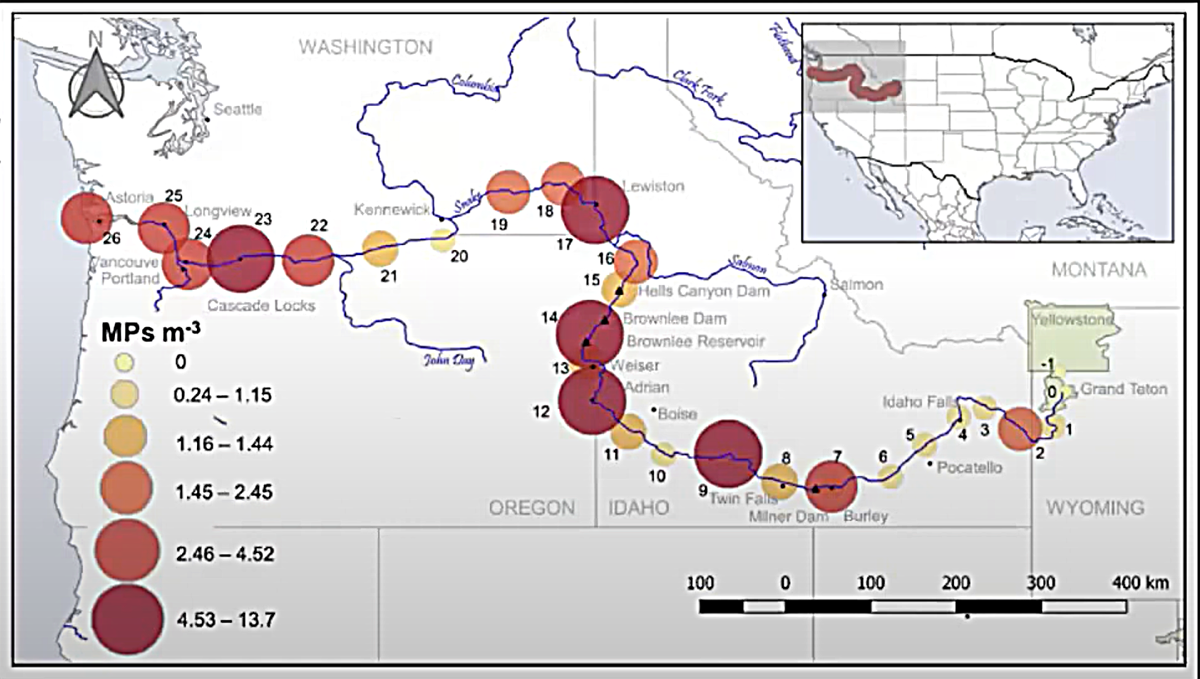

In her study, Professor Kapp and her team took water samples every 50 miles down the Snake River then Columbia River, starting from the Snake’s headwaters in Yellowstone National Park all the way to the Pacific Ocean.

What they found was alarming. A whopping 93% of their samples (collected with mesh nets to catch any debris larger than 100 microns) contained plastic. Using another method, collecting water in jars and then studying the contents, they found plastic in 75% of samples taken.

Concentrations of microplastics (MP) in Snake and Columbia rivers in 2018. Graphic by Kapp/Yeatman/Environmental Pollution

Although the amount of plastic contamination increased the further they moved downstream, the overall levels in the Snake and Columbia were similar—and comparable to levels researchers have measured in New York’s notoriously polluted Hudson River.

Surprisingly, Kapp’s team found some of the largest plastic deposits in areas with little human population. This is likely because these were taken downstream from population centers, as well as in reservoirs where dams collect plastic debris.

What are ‘microplastics’?

Typically, a microplastic is defined as any plastic particle smaller than 5mm—that’s smaller than a grain of rice.

Fiber fighter: Kristen Kapp. Photo: Central Wyoming College

Even at this size, however, microplastics come in many different shapes and sizes.

Most are classified as beads, granules or spheres (as in broken-up polystyrene foam), film (such as plastic bag fragments) and microfibers.

One soda bottle, if not recycled, can eventually create an estimated 39,000 microplastic fragments; a single shopping bag can become 426,000 pieces of microplastic film.

By far the most common type of plastic found, microfibers include fishing line or netting, but also thinner plastic fibers from clothing.

Blame your laundry

There are many ways microplastics find their way into rivers. The most obvious are industrial spills and littering or mismanaged waste. (Only 9% of plastics are being recycled, according to Science magazine.)

Microplastics also spread through runoff from roadways, where bits of tires, which contain plastics, constantly slough off from surface friction.

Agricultural operations are another source. Biosludge from settlement ponds and reservoirs used as fertilizer contains high concentrations of plastic.

MORE: Are you eating your clothes? Microplastics in Columbia River Basin need more study

The most common microplastic culprit, however, is what individuals pour down our drains every day, from body scrubs and makeup with “microbeads,” to household laundry.

“Wastewater treatment facilities actually are quite good at cleaning the water and remove about 90% of the microplastics,” explained Kapp. “But there’s just so much left in that remaining 10%.”

Our laundry, new research has found, appears to be the biggest offender—studies estimate roughly 700,000 plastic microfibers are shed during a single wash cycle, mostly from synthetic fabrics.

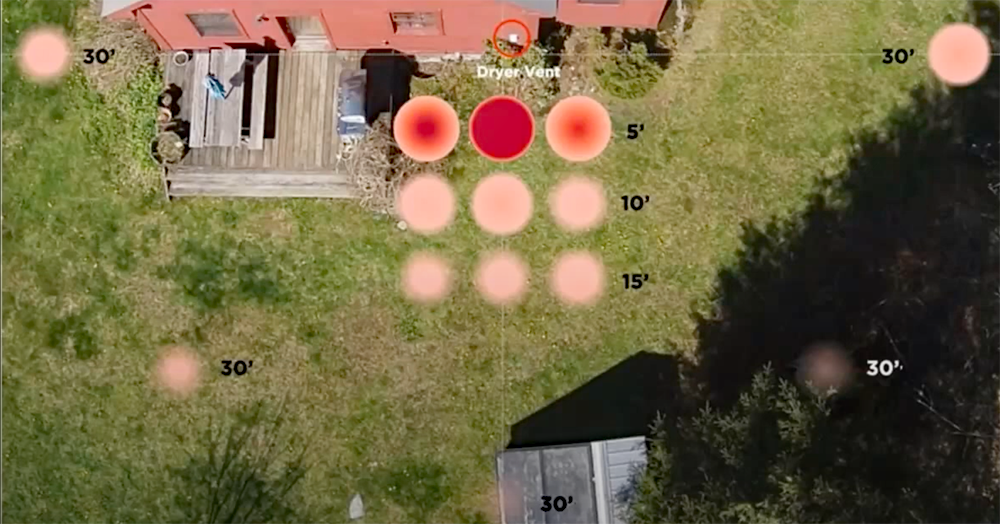

Fly away: Electric clothes dryers are an underestimated source of microfiber pollution. This augmented image shows typical microfiber dispersal from a residential dryer. Image: Kapp/Miller/Plos one

Those same synthetic fabrics can do double damage in the dryer, where they contribute more microfibers through so-called “city dust” or atmospheric deposition, which is blamed for microplastics found in locations as presumably pristine as Arctic ice.

Kapp’s recent experiments on clothes dryers have found microfibers from fleece are dispersed widely through outside dryer vents, even when using lint filters—pointing to dryers as a newly discovered major contributor to microplastic pollution.

Fish ingest plastics

Although microplastics may not be as visibly obvious a pollutant as larger debris, their impact can be more destructive.

To date, more than 200 different animal species are known to have ingested microplastics, including carp, bass, shrimp, albatross, sea turtles, oysters, chickens—even mayflies.

Unseen hazards: Snake River at Hell’s Canyon. Photo: LDELD/CC

Research into the environmental damage caused by microplastics is still in the early stages, but studies have shown they have a range of negative effects on animals, from increased mortality rates, malnutrition and stunted growth to reproductive and behavioral problems.

Pollutants go beyond the plastic itself—microplastics often contain or bond with other harmful chemical pollutants such as polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), fire retardants, pesticides and even pathogens and other disease vectors.

According to Kapp, we don’t yet know how higher levels of microplastics are affecting adjacent issues such as water temperatures, soil pH, soil water retention or root stabilization.

Minimizing your impact

Apart from cutting out all plastics, how can we best address this issue?

“Plastics aren’t going away—we need plastic,” Kapp said. “Plastics are very important in the hospital setting, for one, as we’ve learned during this pandemic. But it’s not necessarily important to eat your meals with plastic.”

MORE: Clamshells begone! Washington takes lead in reducing plastic, boosting recycling

As with many environmental crises, Kapp said, we can’t let a lack of a complete solution be an obstacle to trying to make a positive impact.

“It’s like going into the bathroom and discovering the bathtub is overflowing,” she said. “The first thing you’re going to do is turn off the tap before you start bailing the water.”

Among personal steps she advises to turn off that microplastic tap:

- Push elected officials to institute bans on bags and other single-use plastic items.

- Rethink your choices as a consumer—instead of taking a plastic stirrer for your coffee, use a metal spoon or even a piece of pasta.

- Reuse inherently disposable materials like wrapping paper, which often has a plastic lining, and can easily be replaced with reused fabric.

- Consider adding devices like an aftermarket filter or a Cora Ball, a microfiber-catching laundry ball that can help remove microfibers from wash water before it’s flushed down the drain. Disclosure: Cora Ball was a co-sponsor of the microplastics webinar. [Correction: An earlier version of this story inaccurately identified Dropps as the maker of Cora Ball. —Editor]

- Keep your dryer’s lint filter clean to help collect up to 90% of microfiber pollution.

- Take a hard look at your desire for fast fashion—buy less, wash less, mend more and try to avoid synthetic clothing that sheds microfibers.

Sadly, that last item means thinking critically about the negative impacts even of items we typically think of as helping the environment, such as recycled fleece.

“That’s a really difficult one to answer,” admitted Kapp. “Realistically, fleece is a good product, but it has microfibers that can enter the environment, and we don’t yet know if recycled fleece has a higher shed rate.

It’s the little things: Microplastics are frequently consumed by fish like this rainbow runner from the North Pacific. Photo: 5 Gyres Institute

“But don’t throw out your fleece! One action you can take is to wash your clothes less, wash them on cold cycles and then air dry them.”

That may seem like a minor effort, but the seemingly insurmountable fight against microplastics must start with a lot of single steps.

Charles Coxe has written about environmental issues ranging from ice road trucking in northern Canada to BASE jumping in the Snake River Canyon for publications including Rolling Stone, Life and Popular Science.

Another doohickey? Itself made of plastic? That only catches “up to 31%”? How did this thing make it into your paper? I think I can figure that out. Shame on you!

Hi Michael, I’m a board member with Columbia Insight. We’re an independent & non-profit news site. Like all our board members, we’re really grateful to the donors who keep us going. Our board gets a monthly report on donors and funding, and I can assure you that we’ve never taken any funds from the makers of the “plastic doohickey.” I was more struck by the article’s reminder that for all of us, we can start by doing as many small steps as we can to fight issues like microplastic pollution in the rivers and ocean. If an aftermarket filter of some kind can remove even 31% of microplastics, I’d like to do that, personally. On the funding issue again, we describe our editorial standards on funding and donations on our website (https://columbiainsight.org/policies-and-standards/). If a story is supported by a grant, that information is found at the end of a story. I share your concerns about still more plastics and appreciate you taking the time to read the story. Tracey T

Although the article states that part of the solution for micro plastics is to not buy synthetic fibers it goes on to say that “realistically fleece is not a bad product”, which is misleading.

Synthetic fleece is a petroleum derived product and is bad not only because of its contribution to micro plastics but because of its contribution to CO2 emissions. There are other fibers that are have a significantly lower carbon footprint such as wool, cashmere, mohair, that are equally warm as synthetic fleece. In my humble opinion the best use for synthetic fleece recycled or otherwise is as a weed barrier in your garden, the stuff does not break down :)

A good discussion on the carbon footprint of the textile industry can be found here https://oecotextiles.blog/2011/01/19/estimating-the-carbon-footprint-of-a-fabric/