Too much fire, too little rain and political wrangling over wildlife marked a year of increasing upheaval. Somehow, the planet survived

By Chuck Thompson. December 23, 2021. In July, wildlife biologists in the Selkirk Mountains collared the first female grizzly confirmed in Washington in 40 years.

That same month, tribal leaders met at a “salmon and orca summit” organized by the Nez Perce Tribe and the Affiliated Tribes of Northwest Indians in one of many displays of resolve focused on saving a species—salmon—that unites indigenous and other peoples throughout the Columbia River Basin.

In October, The Dalles, Oregon, sued The Oregonian newspaper in an effort to keep crucial details the city’s $28.5 million water deal with Google hidden from the public.

These events didn’t make our annual list of biggest environmental stories of the year. But 10 others did.

MORE: 10 biggest environmental stories of 2020

Alan Schmierer/CC

In what The Seattle Times called a “surprise attack” and the “Trump team’s parting shot at the Northwest,” outgoing President Donald Trump eliminated protections on more than 3 million acres of northern spotted owl habitat in the final days of his administration. The ruling called for opening large areas of owl habitat in Washington, Oregon and California to logging. After proposing then delaying overturning the order, in November the Biden administration formally withdrew the Trump dig, restoring (for now) habitat protections for the long-embattled birds.

MORE: Spotted owl habitat hatchet job reversed

Cole Burston

After local temperatures hit 121 degrees in late June and more than 29,000 lightning strikes flashed across the province in a 24-hour period, wildfires consumed Lytton, British Columbia, burning almost every structure in the small town. International media descended (above). Lytton had only about 250 inhabitants, but more than 1,000 people lived in surrounding Indigenous reserves. As reported by CNN, every structure in one settlement largely made up of Nlaka’pamux people was completely wiped out, save for one fireproof home.

MORE: Smoke is alive says new wildfire study

Tim Otten/Oregon State University

Three dogs died after playing in the Columbia River. Four others died after swimming in a lake in eastern Washington. Idaho closed popular recreation areas. In one of the year’s most bizarre stories, a family and their dog mysteriously died while on a day hike around California’s Merced River. In each case, toxic algae, or HAB (harmful algal blooms), was the suspected culprit. With spiking temperatures, algal blooms can rapidly rise to toxic levels often marked by a green-ish or brown foam. Human exposure to HAB-inhabited water can cause a range of reactions, from allergic responses to liver and kidney damage. Pets are at more severe risk. Though not a new phenomenon, experts believe temperature levels and proportional HAB growth are steadily rising in lakes across the Columbia River Basin.

MORE: HAB is becoming the acronym of the summer. Now it’s Idaho’s turn

U.S. Department of the Interior

In November, the U.S. Senate unanimously (so they can agree on some things) confirmed Chuck F. Sams III as the first Native American director of the National Park Service. A member of the Cayuse and Walla Walla tribes, which are part of the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation, Sams was selected for his distinguished career in state and tribal land and resource management and sworn in on Dec. 16 by Pueblo of Laguna tribal member and Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland. As Walla Walla’s Union-Bulletin reported: “In Indian Country, Chuck Sams’ nomination to the National Park Service director position represents more than a symbolic victory: it’s a chance to substantively change the way the park service works with American Indian tribes.”

MORE: Umatilla Tribes lead the way in reacquisition of treaty lands

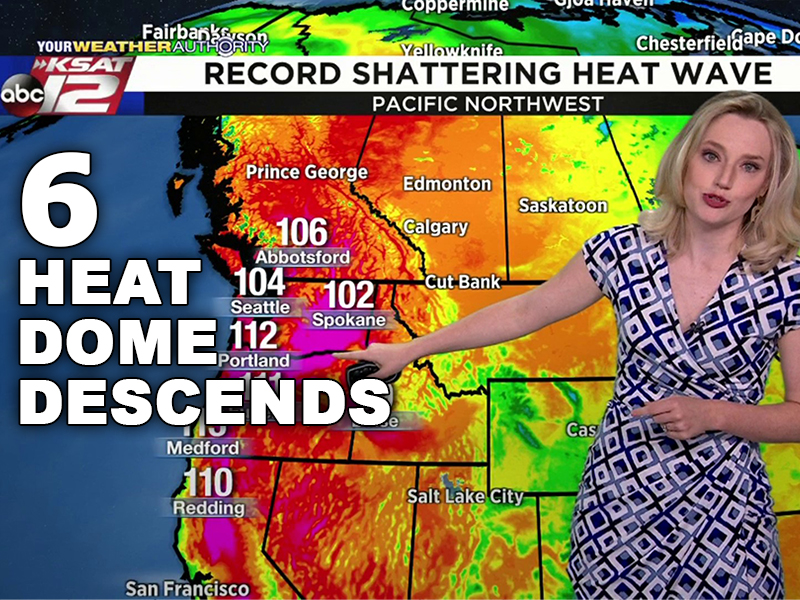

KSAT-TV screen grab

Summer came before summer officially began, with May temperatures in the 90s and consecutive days of triple-digit temps stretching across the Pacific Northwest by mid-June. Record high temperatures were shattered when an unusual weather pattern called a “heat dome” descended over the region, making weather news in such traditional summer hot boxes as Texas (above, San Antonio’s KSAT-TV). The heat was blamed for more than 500 deaths in British Columbia, Oregon and Washington. Crops fried on the vine, livestock and poultry perished, recreation areas were closed. On June 29, Portland recorded its all-time high of 116 degrees, its third day in a row setting a new record. Explained National Geographic amid the crisis: “A heat dome is effectively what it sounds like—an area of high pressure that parks over a region like a lid on a pot, trapping heat.”

MORE: Another extreme heat victim: Cherries

Courtesy of F4WM

National controversy erupted in May when Idaho Gov. Brad Little signed a law permitting the state to hire contractors to kill up to 90% of Idaho’s wolves. The purpose of the new law is to protect cattle and other agricultural assets. “These wolves, there’s too many in the state of Idaho,” said Republican State Senator Mark Harris. The killing of wolves continued across the Columbia River Basin in the wake of the anti-wolf rhetoric. In December, Oregon’s Department of Fish and Wildlife announced a reward of nearly $50,000 for information leading to an arrest related to the poisoning of all five members of Oregon’s Catherine wolf pack and at least three other wolves earlier in the year.

MORE: It’s a trap! Politics, science collide as Idaho wolf law takes effect

W. Tipton/Flickr

March brought news of an audacious proposal by a Wall Street-affiliated company seeking to acquire private water rights throughout the Columbia River watershed in Washington. “The application from Crown Columbia is being considered by (the state’s) Ecology’s Office of Columbia River (OCR) as a way to ‘streamline access to water supply in the Columbia River Basin’ under a single water rights permit,” reported the Methow Valley News. After substantial public blowback, Ecology suspended the proposal. The brazen attempt to grab water rights nevertheless stoked fears across the region about the ongoing gobbling of land and water rights by deep-pocketed private investors, including Bill Gates and the Church of Latter-day Saints.

MORE: As West withers corporations consolidate land and water rights

Courtesy of Mike Simpson’s office

The decades-long fight by environmentalists to breach four dams on the Lower Snake River in order to restore salmon runs got a rocket boost in February when Idaho Republican Congressman Mike Simpson called for breaching the dams as part of his proposed $33 billion Energy & Salmon Concept. Giddy conservationists and liberal politicians including Ore. Gov. Kate Brown lined up in support of the plan. Others, including Wash. Gov. Jay Inslee, rejected it. In May, The Oregonian reported a feud had broken out among GOP lawmakers over the dams. In October, attorney Bryan Smith of Idaho Falls said he’d use the dams to unseat Simpson in their 2022 Republican primary. “I believe that this issue will be the dividing issue that will help me win this race,” Smith told the Idaho Statesman.

MORE: ‘The stars are aligned’: Rep. Mike Simpson breaks down plan to breach Snake River dams

InciWeb

Oregon had the Bootleg Fire. The Red Apple Fire scorched parts of Washington. The Deer Fire burned just east of Boise. It felt odd being on first-name basis with so many fires. But even when you couldn’t remember all the names—nearly 300 burned simultaneously in British Columbia in August—2021 reaffirmed fire season as a 21st-century rite of summer. For a while the Washington town of Winthrop had the poorest air quality in the United States; recreation areas across the region were closed; and evacuations were ordered somewhere in every state (as well as B.C.) in the Columbia River Basin. By mid-August, Northwest Interagency Coordination Center statistics showed the 2021 fire season outpacing even the massive toll exacted by 2020 fires, with Washington and Oregon already having over 20 times more land burned by wildfires than the same time the year before. Final statistics aren’t yet available but no matter what the year’s damage tally wildfires once again made their permanent mark on the region.

MORE: Done fighting: Inside the ‘great exodus’ of wildland firefighters

AP Photo/Nathan Howard

At least 16 Washington counties recorded the driest water year in their history between March and August. “Spring and summer precipitation in Oregon neared the lowest ever level recorded in 127 years of data,” reported Oregon Public Broadcasting. “Meanwhile, high temperatures fueled more evaporation of surface water supplies.” Farmers were hardest hit as reservoirs and irrigation channels ran dry. Faced with record drought in parts of the state, Washington’s winter wheat harvest came in 47% lower than 2020’s yield, and was the worst in at least 30 years, according to the USDA. Idaho’s Magic Valley endured its shortest growing season in seven decades. One of the most severe droughts in the Columbia River Basin’s history is already expected to diminish 2022 harvests. Between June and August, Portland went 51 days without measureable rain. That wasn’t a record but it was a rarity and a spooky indication that even on the “rainy” side of the Cascades water is becoming an ever more precious commodity.

MORE: How a federal program contributed to southern Oregon’s groundwater crisis

With your support Columbia Insight will continue reporting on the most critical environmental issues affecting the Columbia River Basin in 2022.

Chuck Thompson is editor of Columbia Insight.

Leave the wolves alone. Karma can be a bitch,