Progress is slow, but successful tests at the most polluted site in the Western Hemisphere are encouraging

The Hanford Site’s 568 square miles include this hexavalent chromium dig site undertaken to protect groundwater and the Columbia River. Photo U.S. Department of Energy

By Jurgen Hess. September 23, 2021. From the outside, the long and convoluted process of cleaning up the decommissioned Hanford nuclear site in southeastern Washington can seem endless almost to the point of hopelessness.

But a pair of milestones achieved this past summer in the ongoing cleanup saga at Hanford Site is worth knowing about.

In May, the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) announced the site’s Vitrified Low-Activity Waste Facility, known on-site as the Vit Plant, had successfully completed an “effluent management facility” test.

In June, the agency announced a major, remote-controlled crane that handles nuclear-waste canisters had also passed an operating test.

Used to move low-activity-waste canisters, this remote-controlled crane is now in operational order. Photo DOE

Together, the achievements mark important steps toward the goal of creating vitrified nuclear waste at Hanford by 2023.

Conducted remotely by technicians in a control room, the vitrification process at Hanford mixes radioactive waste with sand and other materials. Over a two-month period, the mixture is heated to 2,100 degrees Fahrenheit, a process that melts the sand.

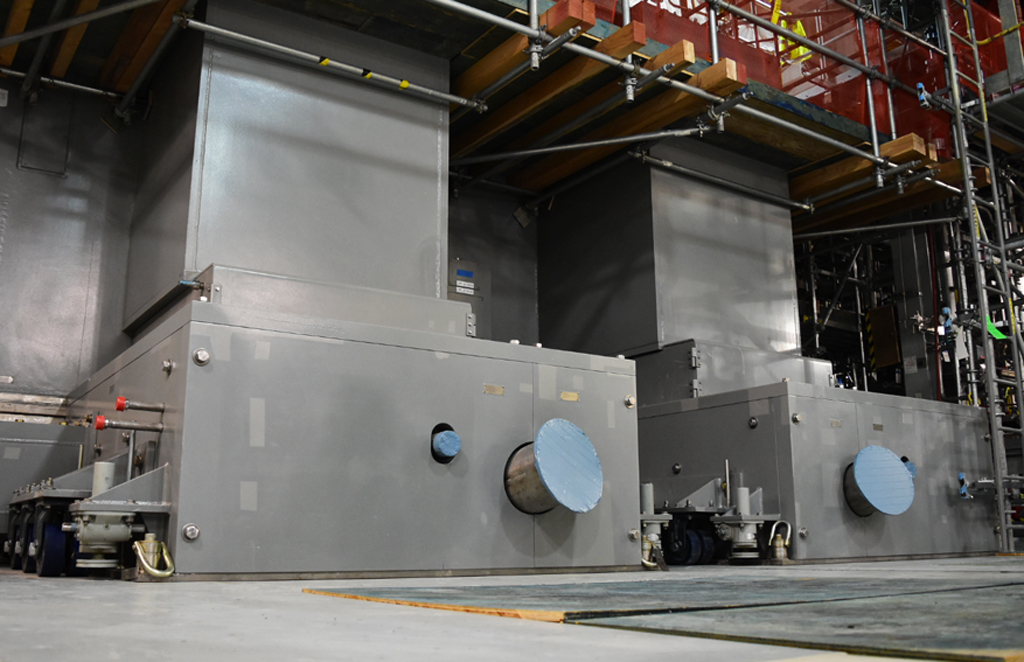

Liquified waste will flow from massive melters into these storage canisters. Photo DOE

The radioactive liquid is then poured into 7-foot-tall, 4-foot-diameter stainless steel canisters that when filled weigh more than seven tons.

As the liquid cools the mixture forms a solid and stable radioactive glass material.

Once online, a pair of 30-ton melters at the Vit Plant are expected to fill 1,100 canisters a year. The canisters will be stored at the Hanford site forever.

Testing is carried out to ensure equipment and systems are functional and in safe working order.

All of this is welcome news at a site with a checkered history.

Toxic legacy

Plutonium production began at Hanford in 1943. Initially, the plutonium was used to build the atomic bomb dropped by the United States on Nagasaki, Japan, on Aug. 9, 1945, effectively bringing an end to World War II.

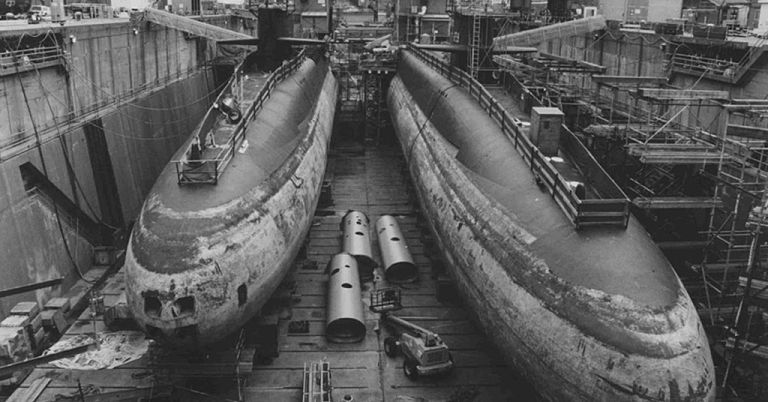

After World War II, Hanford shifted to a Cold War footing, eventually occupying 586 square miles. At its peak, nine reactors were creating most of the plutonium used in the U.S. military’s nuclear arsenal.

The last of Hanford’s reactors ceased operation in 1987, ultimately claiming a key role in the Cold War victory, but leaving behind an unprecedented legacy of environmental pollution.

Constructed during WWII, B Tank Farm was covered with soil to contain radioactivity. The tanks are now leaking. Photo DOE

During Hanford’s four-decade-long heyday, 450 billion gallons of radioactive waste were dumped on the site’s arid shrub-steppe adjacent to the Columbia River. That’s an amount equal to the volume of 682,000 Olympic-sized swimming pools.

With 56 million gallons of radioactive waste stored in 177 leaking underground tanks, Hanford is now regarded as the most toxic site in the Western Hemisphere.

Some liquids have been pumped from single-wall to double-wall tanks, which more effectively contain waste, but a mess of radioactive sludge remains in leaking tanks.

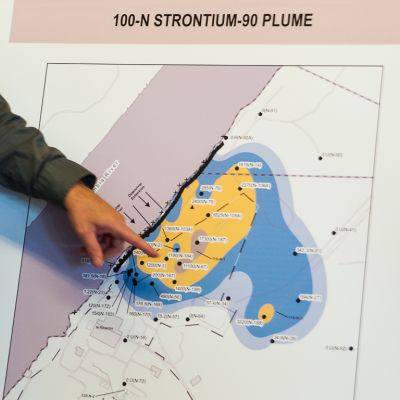

Chart indicates strontium-90 radioactive waste plume entering Columbia River at Hanford 100-N site. Photo by Jurgenhessphotograph.com

Plumes of tritium, chromium, strontium-90 and uranium have reached the Columbia River.

In 1977, the DOE took over administration of what is now officially called the Hanford Site. The 1989 Tri-Party Agreement between the DOE, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and Washington State Department of Ecology governs cleanup of the site, defining roles and responsibilities.

In a 2019 study, the DOE predicted total cleanup costs at Hanford Site would range from $323.2 billion to $677 billion, with DOE continuing an active role until 2095.

The agency has spent about $2.5 billion per year on cleanup. Total personnel involved with the cleanup ranges between 8,000 and 12,000 workers.

Slow going

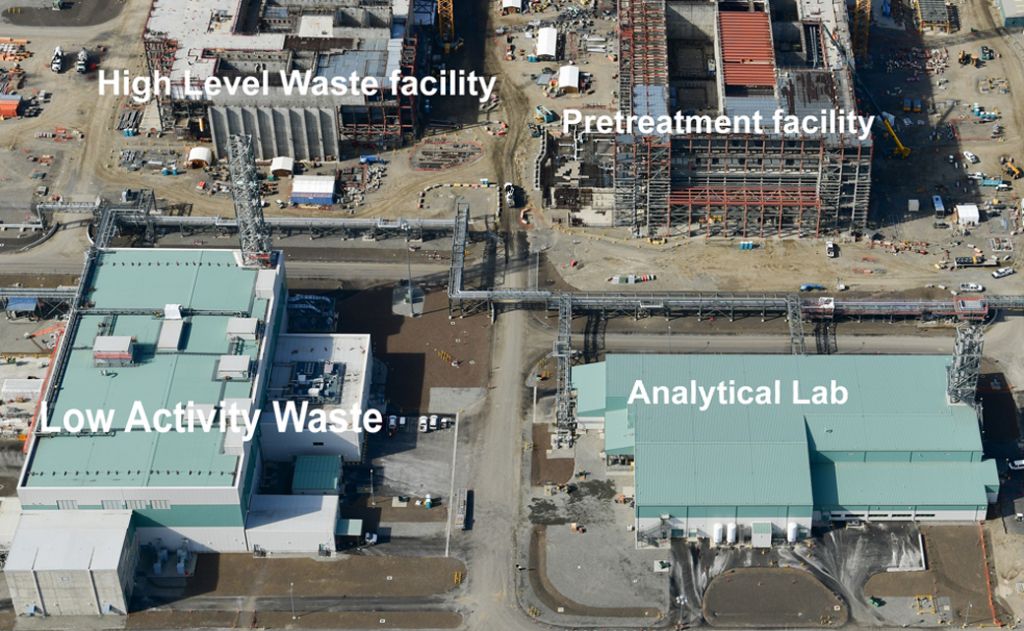

Waste from leaking tanks is treated by Hanford’s $548.4 billion Waste Treatment Plant (WTP). The WTP has four main facilities: High-Level Waste Vitrification Facility, Radioactive Waste Pretreatment Facility, Analytical Laboratory and Low-Activity Waste Facility (Vit Plant).

The Vit Plant is intended to treat 90% of the 56 million gallons of waste stored in the underground tanks.

Its startup is both symbolic of progress being made and a major step in cleaning up Hanford. But it’s nothing close to an immediate fix.

“While it’s great that startup is close, it will likely take more like 40 years to treat all the low-activity waste,” says Jeff Burright, an Oregon Department of Energy radioactive waste remediation specialist.

Former Oregon DOE Administrator Ken Niles says the cleanup has “never felt closer, yet the end is farther away.”

Dan Serres, conservation director and Hanford Site technical expert with Columbia Riverkeeper, has complained that the DOE’s cleanup schedule is too slow to protect soil and groundwater from tank leaks.

Faster fix?

Even as startup of the Vit Plant appears on the horizon, the DOE is studying a cheaper method of stabilizing low-activity waste by using a cementitious grout mixture.

The grout method could potentially save money and stabilize waste faster, but it requires further study. Although the National Academy of Sciences has analyzed the method, the Oregon DOE wants more information about the concept before getting on board.

The Hanford Site Waste Treatment Plant complex. The Low-Activity Waste Facility is expected to begin creating vitrified nuclear waste in 2023. Photo DOE

Hanford tank B109, a single-shell tank, contains 13,000 gallons of liquid radioactive waste currently leaking into adjacent soil at a rate of 1,200-1,500 gallons per year.

Heart of America Northwest, a Hanford environmental watchdog group, is promoting the use of grout to get waste from the tank treated sooner.

The group says low-activity waste can be treated 50 times cheaper and faster with grout than vitrification.

“Federal and state hazardous waste laws say leaking tanks have to be emptied immediately. But USDOE refuses to plan to empty the waste,” wrote Gerry Pollet, Heart of America Northwest director, in an email. “I urge USDOE prioritize funds to remove drainable liquid waste from leaking tank B-109.”

Serres of Columbia Riverkeeper says the grout process likely would be performed at a Perma-Fix Northwest treatment facility close to nearby Richland, Washington. He’s concerned about problems created by moving radioactive waste off-site from Hanford to a remote facility.

Liquified waste will be heated to 2,100 degrees Fahrenheit in these 30-ton melters, then transferred into storage canisters. Courtesy DOE

Serres says he’d rather the DOE construct more double-shell tanks, which are less prone to leaking than single-shell tanks.

DOE’s Burright says the decision whether or not to use grout for dealing with leaked waste from tank B109 will ultimately come from the DOE and Washington Department of Ecology.

No matter what fixes are ultimately implemented, however, this summer’s successful tests at the Vit Plant indicate progress is happening in Hanford Site cleanup … however slowly.

Jurgen Hess is on the Board of Columbia Insight and a member of the Oregon Hanford Cleanup Board. His views are his own and do not reflect positions of either Columbia Insight or the Oregon Hanford Cleanup Board.

Deal that our government has really let the people of Washington n Oregon down. This is too many years of horrible leakage n health problems Seems the dollars are totally waisted on doing nothing for way too many years. This is just pure negligence

Happy to hear of some progress, finally!!