The Dalles’ aluminum smelter closed in 1987 but aluminum recycling and dump sites are still a concern for workers and community

Fumes and flames: A 2019 Oregon EPA inspection of the Hydro Extrusion facility in The Dalles, Oregon, led to a $1.3 million fine for violations of the Clean Air Act. Photo by Oregon EPA

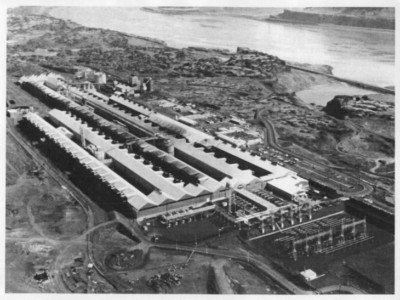

By Valerie Brown. February 4, 2021. Since the early 20th century, The Dalles has been an industrial town, a Carl Sandberg kind of place, muscular, full of the promise of growth based on the spectacular amount of energy available from its own local hydroelectric dam. World War II brought the aluminum industry to the Pacific Northwest, and the Harvey Aluminum smelter (acquired by the Martin-Marietta Aluminum Co. in 1970) became a major employer in The Dalles. Completed in 1958, it kept up to 500 workers in jobs that were steady and paid well.

But soon The Dalles’ other bedrock industry, orchards, was suffering catastrophic failures of crops because the smelter was emitting so much fluorine that blossoms could not set fruit. In the early 1950s there were about 500 acres of peach orchards in the area. None remain today.

The problem was so bad that beginning in 1961 orchardists sued Harvey Aluminum (and then Martin-Marietta) at least 14 times. The plaintiffs weren’t after money—they wanted their clean air back.

Eventually they got some of it back. But The Dalles was still exposed to enormous amounts of pollution from the aluminum smelter, so much that the smelter became a Superfund site when it closed in 1987. It remains subject to monitoring and supervision for the foreseeable future to ensure that cyanide, fluoride, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and sulfates don’t move into surface water, groundwater and soils.

Many residents of The Dalles assume their air quality these days is affected mostly by the AmeriTies railroad tie plant, which sends the odor of mothballs into the air from its use of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, such as naphthalene.

But there’s still an aluminum company in The Dalles. Hydro Extrusion, recycles aluminum—known as “secondary processing” in regulatory parlance—and employs about 70 people. The plant is a subsidiary of Norsk Hydro, a Norway-based multinational.

In January 2020, the Oregon Department of Environmental Quality hit Hydro Extrusion with a $1.3 million fine, the largest fine in the history of the agency, for multiple and flagrant air quality violations, which lasted for more than a year. Following announcement of the fine, an April 2020 Columbia Insight investigation explored community and worker health issues associated with exposures to the chemicals, including aluminum itself, used in recycling.

Dangers of contaminated aluminum scrap

Everybody is exposed to aluminum—it’s the third most abundant element in the earth’s crust. After steel, it has become the second most important metal in modern manufacturing. There are many sources of aluminum exposure, including drinking water, antiperspirants, tea, tobacco smoke and cosmetics.

For most people aluminum comes and goes fairly rapidly, but some of it accumulates in bones and the brain.

Over time, people who work in aluminum processing and residents of neighborhoods near processing sites are likely to be more exposed than the general public to both larger amounts of aluminum and other chemicals used in the industry.

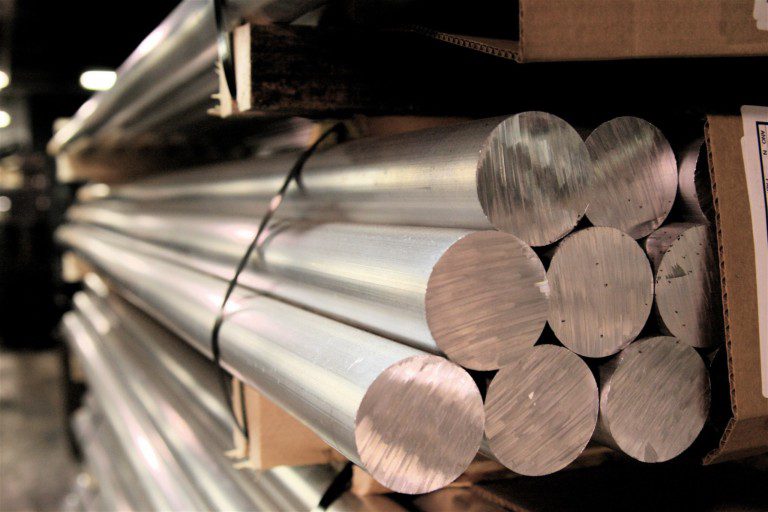

Recycling is considered “green” by comparison to primary smelting of bauxite ore and alumina, demanding only 5 percent of the energy required for the original processing. Hydro Extrusion uses scrap industrial aluminum such as that produced by the Tesla automobile factory in California. The scrap is shredded, melted then shaped into new ingots meeting customer specifications.

Hydro incurred the Oregon DEQ fine because it was using scrap contaminated with “organics,” a term for various carbon compounds like plastics, paper, rubber, grease, marker pen and paint. When burned, organics produce highly toxic dioxins, furans, volatile organic compounds and fluorine and chlorine compounds.

Hydro’s permit does not allow the use of contaminated scrap. DEQ has not indicated whether Hydro’s normal operations violated the Clean Air Act (CAA). But even in normal operations, aluminum recycling emits substances regulated by the CAA, many of which can damage human health.

The CAA encompasses some 187 chemicals that may not be emitted above levels the EPA asserts are protective of human health. Ironically, aluminum itself is not on that list, although it can be extremely toxic to humans, animals and plants.

Exposure to gasses

Recycling aluminum produces fewer, and somewhat different, forms of pollution than smelting its ore. Determining just what Hydro is emitting is not a straightforward process. The DEQ fine was based on observations by EPA and DEQ inspectors who witnessed thick smoke inside the building over two days in April 2019. The inspectors did not have to know what specifically was in the smoke; its very existence told them the scrap was contaminated and the plant was violating the CAA.

The EPA and DEQ inspectors witnessed conditions inside the plant that were unacceptable. For example, the EPA inspector’s report noted that the facility’s four induction furnaces were “open to the building with no exhaust gas ventilation ducting … all exhaust gasses vent into the building.”

Formidable foil: Aluminum scrap awaits processing. Photo by Oregon EPA

This means workers were directly exposed to these gasses, along with fumes and particulate matter. The EPA inspector talked with a 32-year employee who said, “the amount of smoke we were observing was typical.” The DEQ subsequently notified Oregon Occupational Safety and Health of the inspection results.

Since Norsk Hydro bought the plant in 2018, three workers’ compensation claims at Hydro Extrusions have been filed, including one claim for respiratory damage.

In February 2019, about six weeks before the EPA and DEQ inspectors made their site visit, an incident similar to the one inspectors observed in April occurred when thick smoke and fumes filled the room. An employee filed a complaint with OSHA on February 26. A former Hydro Extrusions employee, who spoke with Columbia Insight but declined to be identified for fear of reprisals, confirmed this incident.

One employee left work and went to the hospital, where he was diagnosed with metal fume disease, according to an anonymized claim provided by the Oregon Workers’ Compensation Division. Symptoms of this illness include nausea, fever, chills, muscle and joint pain and headaches.

Metal fume disease is usually “a self-limiting disorder, resolves in a couple of days and has no serious complications or long-term effects,” says Peter Spencer, professor of neurology and occupational health sciences at Oregon Health and Science University in Portland.

Oregon OSHA investigated the February 2019 incident on March 7 and found it to be a one-time occurrence and that the company had adjusted its practices. OSHA took no further action.

Particulates penetrate lungs

The exact chemistry of the furnace emissions in aluminum recycling varies depending on the customer’s requirements. Scrap aluminum usually contains other metals such as magnesium, manganese, copper, lithium and zinc. These may need to be removed or their proportions changed. This is accomplished by adding “flux,” usually fluoride or chloride powder. Flux reacts with unwanted ingredients and workers then scrape it off the top of the melt with paddles.

The products of fluxing become dross, the principal waste product of aluminum recycling. Dross comprises primarily aluminum, sodium and potassium chlorides along with various nitrogen, sulfur, phosphorus and carbon compounds.

Sometimes toxic fumes escape the melt if solid aluminum pieces aren’t submerged quickly enough, or if too much flux is added. The EPA inspector recorded video of such fumes on the day of the inspection. Fumes such as those produced during aluminum recycling are essentially ultrafine particles of metals mixed with volatile vapors.

Smoke show: Oregon EPA 2019 inspection video of Hyrdro Extrusion facility in The Dalles.

Particulates are regulated under the Clean Air Act according to their size, and size matters a lot. For regulatory purposes, particulates fall into two categories: 10 microns in diameter and 2.5 microns in diameter. All sizes are known to cause serious lung injury, but those 2.5 microns and below can reach far deeper into the lungs.

Smaller nanoparticles, such as those in fumes—millionths of microns in size, in the range of viruses—can penetrate even deeper. They can also cross the blood-brain and placental barriers and even travel up the olfactory nerve in the nose to the brain. The CAA does not regulate metals directly but considers particulates an indicator of metal content.

The EPA inspector in 2019 was most concerned about particles 250 microns and larger. Oregon anti-nuisance law prohibits any party from allowing visible deposition on others’ property of particles larger than this. The inspector found that these particles were not traveling beyond the plant’s boundaries, but he also reported that large amounts of fugitive dust were released on the plant grounds while dross was being piled on trucks for removal, and the company was doing nothing to prevent the dust becoming airborne.

For workers, if not the community, this is concerning. Sadie Costello, an occupational and environmental epidemiologist at the University of California Berkeley, has found increased incidence of ischemic heart disease (caused by narrowed arteries) in workers exposed to particulates of 2.5 microns and smaller in aluminum smelters and fabricating facilities.

Ties to neurological disease

There are other, more long-term health risks associated with aluminum recycling, including numerous respiratory problems, neurological disorders, bone damage, cancers and kidney disease. In addition to the various chemicals used in processing, aluminum itself is associated with serious health effects, the most contentious of which is Alzheimer’s disease.

Aluminum is the most abundant material in the air in aluminum recycling plants. Scientists do not yet agree on whether aluminum should be considered a direct cause of Alzheimer’s, but many studies have associated aluminum exposure with neurological problems.

Scientists have known for decades that aluminum is both inflammatory and a neurotoxin.

A clear example comes from people with kidney disease who need frequent dialysis. In the 1980s it was observed that fluids used for dialysis inadvertently concentrate aluminum naturally occurring in water. Some patients receiving high doses developed “dialysis dementia.” Once this connection was recognized, the aluminum content of fluids was reduced and the problem largely disappeared.

Numerous studies have found cognitive decline among workers exposed to aluminum, including from welding and smelter occupations. A large Chinese study of smelter workers in 2019 found that blood levels of aluminum correlated strongly with degrees of cognitive impairment, although education level was identified as a moderating factor. About two-thirds of the subjects had low levels of education.

There is also some evidence that aluminum can have transgenerational effects if it is in the form of nanoparticles. A 2018 study of mice found offspring of mothers exposed during pregnancy to saline solution infused with aluminum nanoparticles suffered from developmental stunting, anxiety and learning and memory deficits. The mouse pups also had significantly higher levels of aluminum in the hippocampus area of the brain. The aluminum had crossed the placental barrier.

Although research is inconclusive, aluminum has also been suggested as a factor in autism spectrum disorder, Parkinson’s disease, multiple sclerosis and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.

Spencer of OHSU remains skeptical of these connections.

“In the ‘90s we’ve seen any number of studies suggesting there might be some association between aluminum intake and neuropsychological changes,” he says. “I would say the jury is still out on this. … It is recognized among workers that aluminum exposure has the potential to build up over time.”

[perfectpullquote align=”full” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]Activities that expose workers to the highest amounts of aluminum pollutants are adding scrap to a furnace and skimming dross from the top of a melt.[/perfectpullquote]

That buildup might make the brain more vulnerable to Alzheimer’s even if aluminum is not a direct cause, says Stephen Bondy, a professor of medicine and pharmacology at the University of California at Irvine. Brain inflammation increases naturally with age and aluminum exposures earlier in life may accelerate the problem.

“If you speed up aging in the brain with early inflammation, you’re speeding up the risk of Alzheimer’s,” Bondy says.

Little is known about the amounts of pollutants that actually get into the bodies of aluminum recycling workers. A British study found that workers in secondary aluminum processing had personal exposures of inhalable dust of 700-5,600 micrograms per cubic meter, about 13 percent of which was aluminum. There were also significant proportions of fluorine salts and smaller amounts of chlorine salts. The activities exposing workers to the highest amounts were adding scrap to a furnace and skimming dross from the top of the melt.

Little information exists regarding the amounts and types of exposure to Hydro’s pollutants experienced by local residents or whether they are suffering from health problems associated with aluminum recycling materials. The relatively small size of The Dalles’ population would make it difficult to obtain statistically significant data for specific neighborhoods. Most available epidemiological data from the Oregon Health Authority does not include data at the city level.

One interesting correlation—not necessarily demonstrating cause and effect—is that the census tract with the lowest life expectancy (73.9 years) in Wasco County (The Dalles is the county seat) is the tract where Hydro is located. The tract with the highest life expectancy (83.2) is in the least populated southern part of the county.

According to the EPA’s environmental justice profile, residents of The Dalles are in the top 2 percent of cities in the state in their proximity to a Superfund site, but lower than the Oregon average for ozone and diesel particulates. This lack of data makes it difficult to determine community-wide effects of emissions.

“The potential drift from the industrial process is one of many concerns for communities near industrial sites,” says Costello. “I expect that aluminum processing particulate exposures to the community would be orders of magnitude lower than exposures to the workers. Thus, for healthy adults, it may not be too concerning, but when one considers babies, children and ill people, then low doses 24/7 can be more of a concern.”

More study needed

One way to answer questions about Hydro’s impact on The Dalles’ air quality and the effects its emissions may be having on public health would be to actually test the ambient levels of pollutants inside and outside the factory and to determine the body burdens of these pollutants in both workers and community members.

Sick burn: Smelting operations took place at the 305-acre Martin-Marietta Aluminum Plant in The Dalles between 1958 and 1987. It’s now a Superfund site. Courtesy of Washington Rural Heritage

“The way to get at this is to use the precautionary principle,” says Spencer, “which is to monitor workers exposed to aluminum fumes or other sources to make sure their urine levels or potentially their plasma [blood] levels are not exceeding what we consider to be acceptable.”

Costello thinks measuring air levels is the most direct way to assess and improve conditions for workers.

“I would encourage factories to conduct good air sampling in the factory, update their equipment to the highest standards and provide personal protective equipment and training for all their workers,” she says.

A former Hydro employee noted that when Norsk Hydro bought the old Northwest Aluminum Specialties and renamed it, new management did provide personal protective equipment to replace the “long-sleeved shirts” that were formerly employees’ only protection.

It is unclear whether Hydro has modernized its venting system to direct gas and fumes away from workers.

After the two severe smoke incidents in 2019, Hydro management introduced further training materials. But these incidents were treated as unusual and not indicative of ongoing worker or community exposures. It’s not known whether Hydro has not conducted any worker bio-monitoring or measured ambient pollution levels inside the plant. The company declined to provide information or consent to an interview with Columbia Insight for this story.

In addition to lack of data about thousands of similar sites across the nation, there are numerous problems with regulation of hazardous chemicals. Occupational health regulations are often geared toward accidents rather than chronic exposures; acceptable exposure levels are calculated separately for each chemical and don’t take into account the effects of combinations of chemicals; and they miss the diversity of chemical exposures’ consequences depending on people’s age, sex and other traits—for example, pre-natal exposures may trigger adult-onset diseases many decades later.

Workers and residents may want to consider ways to get more information about just what hazardous chemicals Hydro is emitting in what quantities and whether they are carrying body burdens of those substances at levels that might affect their health. A way to do this would be to create a crowd-funded project and partner with relevant researchers. The website www.scistarter.org helps citizens devise scientifically valid studies about community issues.

One thing is certain: no matter what such efforts might reveal, the need for jobs and the proud history of The Dalles will temper the community’s choices.

Information in the original version of this article regarding dates and companies involved in aluminum smelting in The Dalles has been corrected and/or clarified. —Editor

Valerie Brown has covered environmental health for more than two decades, publishing in Environmental Health Perspectives, Scientific American, High Country News and elsewhere.

Columbia Insight‘s series focusing on the aluminum industry in the Columbia River Gorge is supported by a grant from the Society of Environmental Journalists.

Columbia Insight‘s series focusing on the aluminum industry in the Columbia River Gorge is supported by a grant from the Society of Environmental Journalists.

I worked at Harvey Aluminum during the 60’s as an electrician and found great esprit de corps by all.I hope somebody replies to my email,Inc. Jack,Hugh,Kenny, Dave,Dennis John, Frank,Wally and many more.I was referred to in many ways and not always as that English man.