Both of Baker County’s bighorn sheep herds have been stricken but the source of the infection remains unknown

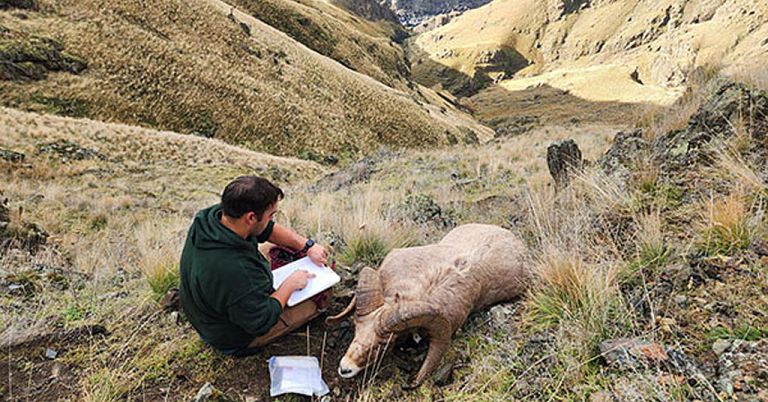

Unseen threat: On Nov. 19, Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife biologists found a dead bighorn ram a few miles west of the Brownlee Reservoir on the Oregon-Idaho border. File photo by Nick Myatt/ODFW

By Jayson Jacoby, Baker City Herald. December 1, 2020. State biologists have confirmed that the outbreak of pneumonia that has sickened and in some cases killed bighorn sheep in both of Baker County’s herds was caused by the same strain of bacteria.

Lab results last week showed that a sheep from the Burnt River Canyon herd that died in October was infected with Mycoplasma ovipneumoniae bacteria.

That’s the same strain of bacteria found in tissue samples from bighorn sheep in the Lookout Mountain unit that died last winter and spring, said Brian Ratliff, district wildlife biologist at the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife’s (ODFW) Baker City office.

The confirmation that the same bacterial strain infected sheep from both herds answered one question, but others remain, Ratliff said.

Biologists don’t know the source of the bacteria, which had not been confirmed in bighorn sheep in Oregon until February 2020, when a lab test detected the strain in a dead sheep found along the Snake River Road. That sheep was from the Lookout Mountain herd, which ranges north of Interstate 84 and west of Brownlee Reservoir.

There are more than 50 strains of Mycoplasma ovipneumoniae, and they have varying levels of lethality, Ratliff said.

He said biologists don’t know how many sheep have died, from either the Lookout Mountain or the Burnt River Canyon herds. At least a dozen Lookout Mountain sheep died this winter and spring, and at least three Burnt River Canyon sheep died in October.

Ratliff said biologists found a dead sheep in the Burnt River Canyon on Nov. 17. He said he hopes to have a more precise death tally later in December after taking helicopter flights in both areas to count sheep.

Baker City’s two herds

The Lookout Mountain herd has been Oregon’s biggest herd of the Rocky Mountain subspecies of bighorns, with about 400 sheep.

The Burnt River Canyon herd, which lives in the rugged canyon about 20 miles southeast of Baker City, consists of the California bighorn subspecies. The herd numbered about 85 animals.

Ratliff said bighorn sheep from both subspecies are susceptible to many types of bacteria and viruses that cause potentially fatal pneumonia. He said sheep can be infected by nose-to-nose contact with domestic livestock, typically sheep or goats.

Ratliff said the Mycoplasma ovipneumoniae is not known to be carried by cattle.

[perfectpullquote align=”full” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]The bottom line is “we just don’t know” the source of the bacteria that infected the two bighorn herds.[/perfectpullquote]

There are domestic sheep herds on private land in the Durkee Valley within a few miles of the mouth of the Burnt River Canyon, Ratliff said. None of those sheep has been tested for the strain of bacteria that infected the bighorns.

Ratliff said domestic sheep have lived near the Burnt River Canyon since ODFW reintroduced bighorns to the canyon in 1987, and there’s been no evidence of widespread pneumonia in the herd until this year.

Domestic sheep also graze on a public land allotment, overseen by the Bureau of Land Management, in the Lookout Mountain unit, Ratliff said. He said that allotment is actually closer to the Burnt River Canyon herd, albeit with Interstate 84 in between. None of the domestic sheep that graze on that allotment has been tested for the bacteria.

Sheep from two other domestic flocks near Richland, at the north end of the Lookout Mountain unit, were tested earlier this year and none was carrying the Mycoplasma ovipneumoniae bacteria. A llama owned by a resident along the Snake River Road was also tested, and was also negative for the bacteria.

The owners of those animals volunteered for the tests, which ODFW paid for, Ratliff said. He welcomes owners of sheep and goats in either area to call the ODFW office at 541-523-5832 if they’re interested in having animals tested.

Tracing the illness

Ratliff said it’s plausible that the Baker County bighorns were infected by contact with other bighorn sheep, possibly from Idaho.

The bottom line, he said, is “we just don’t know” the source of the bacteria that infected the two bighorn herds.

Ratliff is confident, however, in saying that whatever the source, sheep from the Lookout Mountain herd were infected first.

The reason, he said, is timing.

Lookout Mountain bighorns were infected some time before Feb. 13, the day biologists, responding to a report from a passerby, found a dead bighorn ram lying on the Snake River Road near Connor Creek, about 18 miles north of Huntington.

Ratliff said the first evidence of illness in Burnt River Canyon bighorns didn’t show up until October.

Although he acknowledges it’s possible that bighorns from each herd were infected separately, from different sources, Ratliff said he thinks that’s highly unlikely.

He’s skeptical of that scenario largely because evidence is mounting that Burnt River Canyon and Lookout Mountain bighorns mingle more often than biologists had believed.

The two herds generally are 10 miles or so apart, and with Interstate 84 between them. But early this summer, two young rams from the Burnt River Canyon herd tried to cross the freeway from the south (Burnt River) side to the north, Ratliff said. One of the rams was hit by a car and killed. A tissue sample from that ram did not contain the Mycoplasma ovipneumoniae.

Ratliff said that had he been asked a year ago to estimate the relative risk of Baker County bighorns contracting a bacteria or virus from domestic sheep, he would have rated the Burnt River Canyon as more vulnerable because of the proximity of domestic sheep in Durkee Valley.

“I would have been wrong,” he said, citing his belief that the Lookout Mountain bighorns were infected first.

Recent ram death deepens mystery

Ratliff said that on Nov. 19, ODFW biologists found a dead bighorn ram near Little Deacon Creek, a few miles west of Brownlee Reservoir and near the geographic center of the Lookout Mountain herd’s range.

Ratliff said the ram definitely died from pneumonia, although he has yet to receive a lab result confirming the animal was infected with the same strain of bacteria.

But the more significant part of the story, he said, is that he’s all but certain—again, pending lab confirmation—that the dead ram wasn’t from the Lookout Mountain herd but rather from the Burnt River Canyon herd.

Ratliff said the ram, which was nine to 10 years old, is about one-third smaller, both in body size and horns, than a typical mature ram of the Rocky Mountain subspecies. The ram’s size was consistent, however, with the smaller California subspecies, and Ratliff believes the ram migrated from the Burnt River Canyon herd—further evidence that the two herds mingle.

What’s impossible at this point to determine, Ratliff said, is how the bacteria spread from the Lookout Mountain herd to the Burnt River Canyon sheep.

Either Lookout Mountain sheep crossed the freeway and mingled with Burnt River Canyon sheep and infected the latter, he said, or Burnt River Canyon sheep made the journey, became infected from contact with Lookout Mountain sheep, then returned to the Burnt River Canyon and spread the bacteria among that herd.

Biologists found the dead ram while working on a project to learn more about the prevalence of the bacteria in Lookout Mountain sheep. Biologists used tranquilizer darts to capture sheep, take tissue samples for lab testing and attach tracking collars to the animals.

ODFW has collared nine sheep during the operation, with about a dozen collars remaining.

Collaring bighorns will allow ODFW to employ the “test/cull” strategy if the illness is so prevalent, and lethal, that it threatens the future of the entire Lookout Mountain herd.

Biologists can track the collared sheep and test them occasionally for the bacteria. That’s important, Ratliff said, because some sheep are likely to be “intermittent shedders,” meaning they carry the bacteria but shed it only some of the time.

Those that are actively shedding bacteria could potentially be euthanized to prevent them from infecting others.

The Lookout Mountain herd was established in the early 1990s when a few dozen bighorns were captured elsewhere and released along Fox Creek. The animals have thrived in the steep canyons on the breaks of the Snake River.

Columbia Insight is publishing this story as part of the AP StoryShare program, which allows newsrooms and publishing partners to republish each other’s stories and photos.