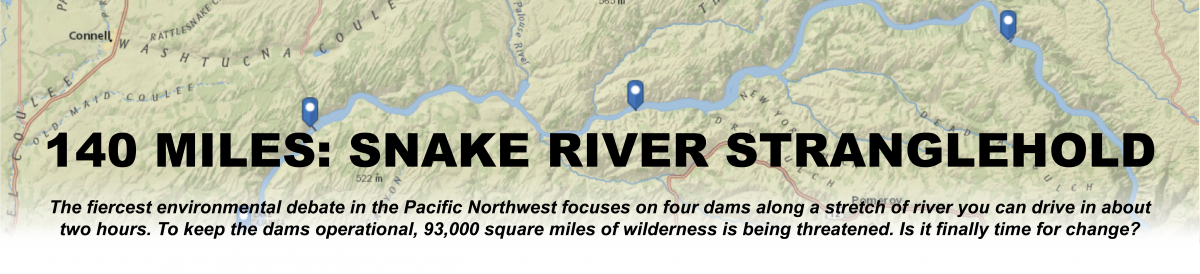

Thought the Snake River dams controversy had finally been put to bed? Environmental groups across the Columbia River Basin aren’t ready to go down just yet

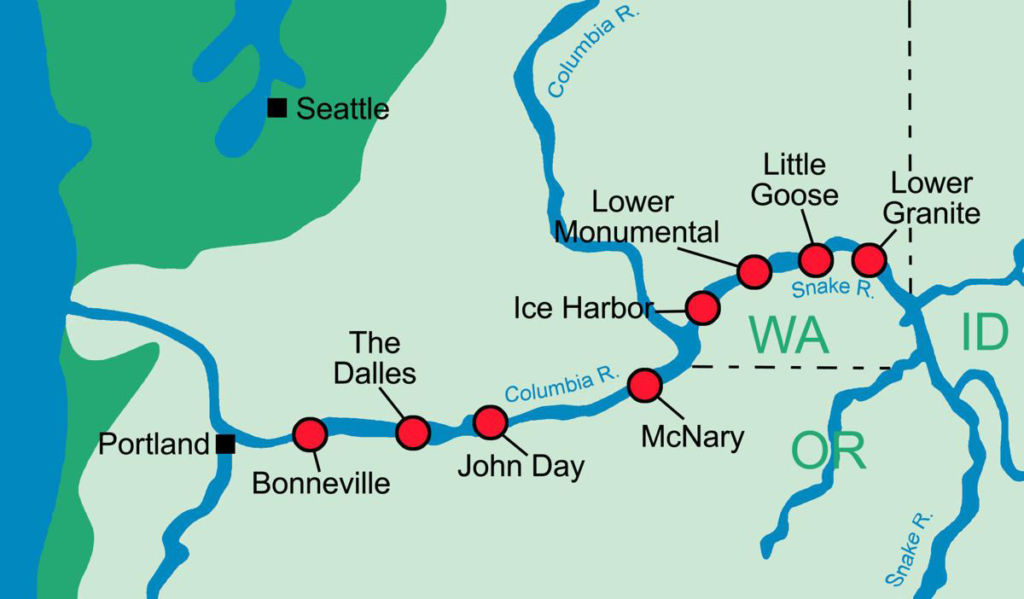

Hard lines: Starting with Ice Harbor dam and moving east (red dots indicate dams), a coalition of 11 groups wants four Snake River dams breached. The federal government isn’t budging. Courtesy of U.S. Army Corps of Engineers

By Chuck Thompson. October 29, 2020. If we learned one thing last week about the federal government’s insistence on maintaining operations at four controversial dams along the lower Snake River it was this: the opposition is unimpressed.

On September 28, following a four-year, court-ordered environmental study, a group of federal agencies announced its business-as-usual decision on the dams. On October 22, a coalition of 11 environmental and fishing organizations announced its intent to sue the federal government based on its opinion that the decision violates the Endangered Species Act.

The 60-day notice of intent to file a lawsuit Fed Ex’d to the heads of seven government agencies by legal firm Earthjustice marks at least the sixth incarnation of the long-running court battle focused on breaching the dams.

Critics say the dams must be breached in order to restore endangered salmon and steelhead throughout the Columbia and Snake River watersheds. The four dams, each located in Washington, block fish passage from the Columbia River along the lower Snake River into cold-water spawning streams in central Idaho.

MORE: The return of Clearwater coho

The watershed once produced the world’s largest salmon run. Sockeye salmon, chinook salmon and steelhead are now listed as threatened or endangered in the Columbia and Snake Rivers.

“The failure of this federal plan to adequately address the rapid extirpation of salmon and steelhead in Idaho and the Snake River Basin cannot be overstated,” said Nic Nelson, executive director of Idaho Rivers United, in a press release that accompanied the Earthjustice announcement. “Instead of proposing solutions that get us to an abundance of wild fish, this continues down the decades-long path of failed recovery efforts.”

“Independent researchers who have studied the economics of restoring a free-flowing lower Snake River and renewable power replacement options favor dam removal,” according to Earthjustice.

Hanging on: Secretary of Commerce Wilbur Ross was one of seven federal agency heads to receive an Intent to Sue notice from Earthjustice. Photo by Gage Skidmore

In its court-ordered Environmental Impact Statement, the government also determined that breaching the dams would be the best way to restore salmon. But in assessing dam operations, the agencies said they weighed environmental issues against the impacts to flood risk management, water for irrigation, shipping, hydropower and recreation.

In its September joint Record of Decision, three federal government agencies that control the dams—the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Bureau of Reclamation and Bonneville Power Administration—said that rather than breach the dams they would increase the amount of water spilled over them in spring to aid juvenile fish heading downstream.

Environmentalists immediately voiced displeasure.

Signatories to the new legal challenge are: American Rivers, Idaho Rivers United, Institute for Fisheries Resources, NW Energy Coalition, Northwest Sportfishing Industry Association, Natural Resources Defense Council, Pacific Coast Federation of Fishermen’s Associations, Sierra Club, National Wildlife Federation, Columbia Riverkeeper and Idaho Conservation League.

What’s different this time?

Environmental groups have vigorously opposed the dams since even before the Corps of Engineers built them in the 1960s and ’70s. But legal efforts as well as campaigns to generate widespread public support for their cause have so far failed to budge the federal government from its own intransigent position.

So what gives opponents optimism this time around? Why might a sixth legal challenge produce a different result than the five previous efforts?

Critics such as writer Steven Hawley and producer Michael Peterson argue that largely due to the emergence of wind and solar power, the dams are now money losers that have become hydroelectric redundancies on the larger power system. In 2019, the pair made the documentary Dammed to Extinction, which directly linked the dams to the decline of endangered Southern Resident orcas in Puget Sound, whose diet relies almost exclusively on the chinook salmon from the Columbia-Snake system.

MORE: Hydro hypocrisy: ‘Dammed’ filmmakers tie Snake River dams to declining orcas

For backers of the renewed legal challenge, however, part of the problem is simply that what’s old is new again.

“This plan looks a lot like the plan the court looked at in 2016 and said doesn’t comply with the law,” Todd True, senior staff attorney at Earthjustice’s Northwest regional office in Seattle, told Columbia Insight this week. “If, like I am, you’re familiar with the history of this controversy in court, the (government) plan does not look like a serious effort to do what the court said to break the logjam. It looks like more logjam.”

“It is disappointing—but not at all surprising—to see the same litigious special interest groups attacking this administration’s robust, transparent, science-based environmental review of the Columbia River system, just as they did with the Obama Administration’s previous review,” Washington Rep. Dan Newhouse (R) told the Idaho Statesman.

True rejects that interpretation.

“Some of the reaction to the 60-day notice was, ‘Well, these guys can’t be serious about wanting to work with people if they’re going back to court.’ That’s just dead wrong,” said True. “In our view having the accountability a legal challenge can provide … is an important backstop to that effort to bring people together and solve the problem. Because one thing is for sure if we just keep kicking the can down the road the salmon will go extinct.”

Chuck Thompson is the editor of Columbia Insight. Columbia Insight‘s series focusing on the Lower Snake River dams is supported by a grant from the Society of Environmental Journalists.

” The four dams, each located in Washington, block fish passage from the Columbia River along the lower Snake River into cold-water spawning streams in central Idaho.” Forgot to mention the fish ladders on the four dams in question.