Our conversation with historian Thomas Cox covers a lot of ground, including reasons the Greater Idaho movement is “nonsense” and why Samuel Boardman is still an Oregon hero

Getting along: More than 85% of Oregon-grown wheat is exported, making it the #1 product shipped overseas through the Port of Portland. The relationship between interests east and west of the Cascades isn’t always so cut-and-dried. Photo by Jurgen Hess

By Don Campbell. October 8, 2020. You’d be forgiven for thinking, like many, that most of Oregon’s vitality resides in the fertile hills, valleys and coastline on the west side of the state’s majestic Cascade Range. Much of its economic fuel, political and cultural energy and population density are produced in this western swath—from the Columbia River, south through the Willamette Valley and down to the California border.

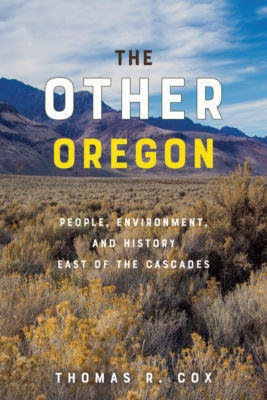

But up over those mountaintops to the east spreads a unique and compelling grandeur that historian Thomas Cox captures in his highly readable and well researched book, The Other Oregon: People, Environment, and History East of the Cascades, published last year by Oregon State University Press.

Cox begins by noting how the Cascade Range splits the state “into two dissimilar entities. The land east of the Cascades makes up some two-thirds of the state, yet somehow it is not viewed as part of the ‘real’ Oregon.”

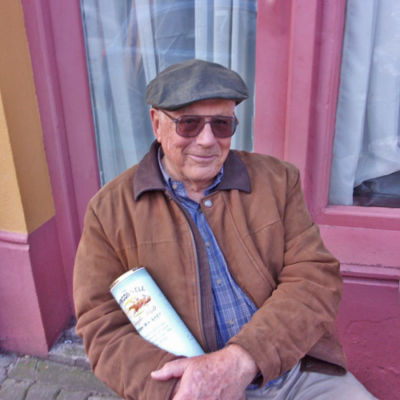

Cox, who grew up in Central and Eastern Oregon and now lives in Idaho, deep dives into the region’s geography, environment, economy, culture and, perhaps most importantly, the people who have attempted to survive, tame and thrive in this wild country.

Columbia Insight: What compelled you to tackle a book on the complexities of this region you call a “hard, haunting, somehow beautiful land”?

Thomas Cox: Growing up in Central Oregon and traveling far and wide east of the Cascades I developed a deep, abiding love for the region. Over the years I continued to be intrigued by how different “the dry side” is from the rest of Oregon. Finally, after a long career as an environmental and economic historian, I felt I had to wrestle with the what and wherefore underlying these differences. It is a story that revolves around the relationships of the people and the land and as such has lessons not just for folk living east of the Cascades, but for people everywhere.

Boundless resource: Cox’s book functions as both an academic and popular history.

CI: Why do you think there’s such a cultural divide between Oregon’s east and west sides of the Cascades? And what might it take for both sides to bridge that divide, specifically in terms of thinking about things like resource extraction, salmon habitat, climate change and other environmental issues?

TC: There are huge differences between the lands east and west of the Cascades, differences that transcend the internal variety within each. These differences and the varied opportunities they present attracted different brands of settlers to Eastern and Western Oregon. These settlers brought cultural values with them that shaped social norms—and have continued to shape the societies down through the years. The differences shape much of today’s contrasting political and environmental discourse on the two sides of the Cascades.

CI: Was there anything you found in your research that changed your perception of the region where you grew up?

TC: The more I dug, the more the commonalities among the various parts of Eastern Oregon became evident—and the more the differences between it and Western Oregon became manifest. The differences proved both more enduring and deeper, the similarities fewer than I had expected to find. I had anticipated a gradual convergence as the pioneer period passed; it occurred, but never to the point that similarities outweighed the contrasts.

CI: What do you feel are the most pressing environmental issues east of the Cascades and into Idaho?

TC: Today the most pressing need is to find ways to bring together people with differing ideas and agendas so that mutually acceptable solutions to environmental issues may be found. No one group has a monopoly on an understanding of the land. The need for this cooperative approach is especially evident in the area’s timber country, but is present elsewhere as well.

CI: How did the events at the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge influence your writing? It made a compelling final chapter to your book.

TC: The takeover of the Malheur Wildlife Refuge in 2016 provided a vivid example of what can happen when cooperation is replaced by a “my way or the highway” approach. It showed how outsiders and locals, seeing things from different vantage points, can arrive at solutions sharply at odds with one another.

At the same time, both here and elsewhere in my study, I argue that all too often federal authorities have failed to appreciate—and incorporate—the understanding of problems that is possessed by those who actually live on the land. Such a failure can—and in the case of the Malheur Wildlife Refuge did—contribute to unfortunate outcomes.

CI: What are your thoughts on the resurgent “Cascade movement” to make Eastern Oregon part of Idaho? What drives it and is there any credence to it?

TC: The Cascade or Greater Idaho movement is nonsense. Today Oregon’s outback and Idaho may both have a tendency to vote for conservative Republicans, but that is about all they share. Oregon has long prided itself in its public schools and has funded them relatively well; Idaho’s schools rank near the bottom of the fifty states. Oregon has rejected a sales tax time and again, largely because it is so sharply regressive in nature; Idaho leans heavily on the sales tax, and the large landowners and big businesses are anything but overtaxed.

I find it revealing that when my older nieces were growing up in Ontario [Oregon], they looked on Idaho with disdain; they were hardly alone. On the other hand, the argument that Idaho would benefit because it would then have a seaport that would give its economy a boost is specious. Idaho already has a seaport, Lewiston, while Coos Bay, the seaport it would gain, has a limited hinterland that does not extend anywhere close to Idaho.

The political domination of the Portland-Eugene axis in Oregon’s politics fuels a lot of angst east of the Cascades, but it certainly does not make it a likely handmaiden of Idaho—which, by the way, has divisions of its own. It is often said that Idaho is the only state with three capitals—Salt Lake City, Spokane and Boise.

CI: I’ve long felt that, federally, one Democratic senator and one Republican best represent Oregon’s character and capture attitudes on both sides of the Cascades, especially in terms of the environment, environmental justice and the like. Your thoughts?

TC: That Oregon has both Democratic and Republican members of Congress should come as no surprise in light of the regional differences within the state. But one should be cautious about reading too much into this. Democrat Al Ullman long represented Eastern Oregon in Congress. Republican Tom McCall was from Central Oregon—in spite of his career as a Portland newsman—and his conservative, prop-business nemesis Victor Atiyeh was from Western Oregon.

Historically, party machines have been notoriously weak in the state. Politicians built their own support networks/allegiances, and to an extent they still do. I remember in Mark Hatfield’s day they had trouble finding someone to take the Republican state chairman position because it was so irrelevant. Hatfield had his own support network, there really wasn’t much for the state chairman to do.

CI: Growing up I was always proud of Oregon’s state park system, so I found chapter 14, “In Nature’s Realm,” fascinating in regard to Samuel Boardman and others’ foresight in capturing some of the truly spectacular landforms in Eastern Oregon. In light of climate change and economic greed, are we doing enough to preserve, maintain and promote Oregon parks?

TC: Oregon’s state park system is something to be proud of, and Sam Boardman and Robert W. Sawyer, who together laid the groundwork, continue to be two of my heroes. I detail the parks story in an earlier book, The Park Builders [1989]. What I say about parks and outdoor recreation in The Other Oregon builds on that. As patterns of travel (and) tourism change, the role of parks has evolved and, unfortunately, the level of state financial support has eroded.

Colorful career: A former president of the Forest History Society, Cox has worked as a firefighter, sawmill grunt and high school football coach. Photo courtesy of Thomas Cox

CI: Was it difficult researching the Native Americans who populated Eastern Oregon? It almost seems like a companion book could be written about their way of life in that region

TC: Dealing with the history of Native Americans is fraught with special difficulties. Sources, both Indian and white, need to be used with care, for they often are far from impartial, limited in perspective and almost invariably less than thorough.

Fortunately there have been good studies of the Klamath and Warm Springs reservations and of the Celilo fisheries for me to draw upon. There is little on the Umatilla Reservation tribes, less yet on the Burns Paiutes and almost nothing on the Fort McDermitt Reservation. I am in the process of trying to pull together a book on the Burns Paiutes. Hopefully, I will be able to properly represent all sides of the story, but it is a daunting, often frustrating undertaking that will probably take years.

CI: What are the common character traits, appetites, philosophies, idiosyncrasies and/or proclivities of those who live in Eastern Oregon?

TC: People east of the Cascades hold a variety of outlooks, attitudes and values. They are no more uniform than the people of any society. In The Other Oregon I attempt to demonstrate these variations and the conflicts that sometimes result from them.

If one must generalize, it would probably be safe to say that there is a connection to the land not seen to the same degree in folk who live in built environments or places like California’s Central Valley, altered to the point that even the land seems a manmade entity hard to love. I am inclined to believe that the long vistas and rugged landscapes of Eastern Oregon encourage a breadth of vision, a sense of place and a tendency to take one’s leisure in the out-of-doors to a degree seldom found west of the Cascades.

CI: How long did it take to research and write the book?

TC: Time? My wife would say “forever!” As I say in my foreword, I have toyed with the idea of doing such a study since I was an undergraduate in the 1950s, but I did not undertake real work on this book until after I retired and moved to Idaho—to a place rather like Central Oregon used to be.

I finished The Lumberman’s Frontier in 2010. Only after that did I start trying to pull The Other Oregon together, sometimes using materials from some of my earlier work, sometimes expanding and re-interpreting it and sometimes incorporating new material and ideas. The process was slowed—and aided—by the need to incorporate, or argue with, the outpouring of relevant work by others in recent years.

But using the 1950s as the gestation point for my original ideas, my wife comes closer to the truth than I care to admit—“forever.”

Don Campbell is a Pacific Northwest writer who currently lives in Mosier, Oregon.

I’m buying the book.

Hi Tom!

I really enjoyed reading your interview. I think of you, Mary, and Michael Often and miss your company. I’m going to order your new book, and hopefully see you all when this pandemic is finished running its course.

With respect, love and much appreciation,

Victor

From the interview I doubt the author really spent much time with real people. The cultural divide is wider than he thinks, especially where politics are concerned. People are more tied to the land in eastern Oregon and value their freedom more. There are commonalities but the differences are wider..

I’m not sure what in the interview led Duane Lee to the conclusions he draws. Suffice it to say, I think his critique misses the mark. “Real people”–and their views–dominate the book; technocrats and otger “experts” are taken to task time and again.