Photo by Jurgen Hess

By Dac Collins. Feb. 20, 2020. Search Google images for “climate change” and you will see burning forests, melting glaciers and a hurricane pinwheeling off the coast of Florida. Keep scrolling and you’ll find photoshopped images of the Earth catching fire, along with despondent polar bears adrift on icebergs. Scroll a little further and you’ll see the Statue of Liberty standing neck-deep in New York Harbor.

These are all creative depictions of the effects of climate change. Are some of them over-dramatized? Surely. Straight out of Hollywood? You bet. But to quote one of today’s most unquotable philosophers: “Our art is a reflection of our reality.”

Now scan through these images once more and you’ll notice another recurring theme: pictures of power plants and industrial smokestacks spewing clouds of pollution into the air.

These pictures have become so synonymous with the notion of human-caused climate change that they have become its go-to symbols — its scapegoats, if you will. And for good reason.

But no matter how far you scroll through this seemingly bottomless well of images, you will not find a single picture of an automobile, a diesel truck or a crowded highway.

Which seems strange, if not wrong…seeing as transportation is now the biggest source of carbon emissions in the United States.

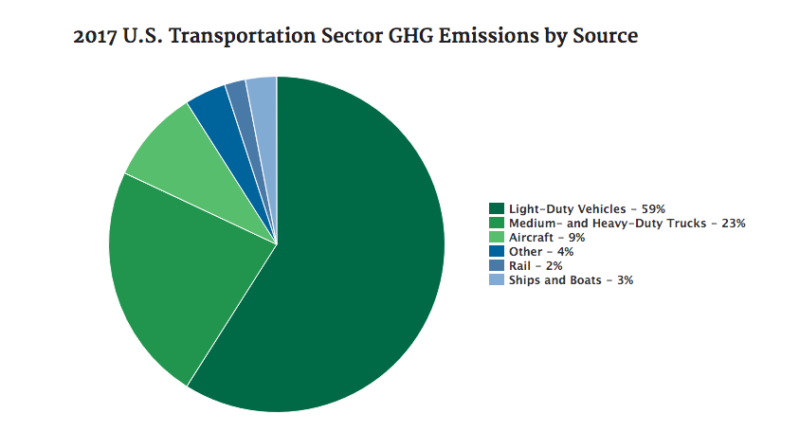

According to the Environmental Protection Agency, the transportation sector made up 29% of the country’s greenhouse gas emissions in 2017. And of that percentage, a majority of those emissions were released by what the EPA calls “light-duty” vehicles — our rides, pickups, wheels, jalopies, coupes, clunkers, whips and minivans. Our daily drivers.

Graph courtesy of the EPA

So why the disconnect?

Is it because we would rather view climate change as a byproduct of some force that is beyond our control? Because we’re so used to blaming energy companies, greedy corporations and incompetent presidents pushing corrupt policies? Or is it simply that Americans — the free-spirited inventors of the Mustang and the monster truck — love our cars far too much to blame them for the mess we’ve found ourselves in?

Perhaps it’s a mixture of all three. But any country whose citizens spend their weekends drinking light beer and losing their hearing while stock cars race around in a circle 200 times should probably take some time for self-reflection.

A culture steeped in Cadillacs

Now that we’re looking in the rearview, we can see that for the last century or more, we’ve built our transportation systems around a pillar of American culture: the private car.

It’s hard to determine exactly when America fell in love with the automobile, but it probably happened sometime between the invention of the Model-T in 1908 and the first recording of “Not Fade Away” in 1958. (At one point in the song, Buddy Holly sings that his “love’s bigger than a Cadillac”…but he never got to see the 2020 Escalade ESV.) A number of artists would follow suit, writing hits about the quintessential Caddie during the latter half of the 20th century — from Johnny Cash and Bruce Springsteen to The Clash and Outkast.

By 1980, roughly 87 percent of American households owned one or more vehicles. And in September of 1997, The New York Times ran this headline: “Number of Cars is Growing Faster Than Human Population”.

This advertisement for a Cadillac Sedan deVille ran in a 1959 issue of Life Magazine. Photo by Brian

Fast forward to today, and we’re still singing about Cadillacs.

So it’s only natural that when we start having real discussions about how to tackle climate change — and how each and every one of us can decrease our own carbon emissions — the private car takes center stage. A nation of innovators, we point to electric vehicles and hydrogen fuel cells as the best possible solutions. And they are certainly part of the solution.

But electric vehicles and alternative fuels have their own challenges and limitations (more on that in an upcoming story*). And while changing our cars will be a priority in the years to come, we also have to consider another, more comprehensive approach: changing our culture and embracing public transit.

To put it simply, buses and trains can move more people with fewer vehicles. And fewer vehicles translates to less carbon emissions. According to the Federal Transit Administration: “Public transportation produces significantly lower greenhouse gas emissions per passenger mile than private vehicles…with light rail systems [producing] 62% less and bus transit [producing] 33% less.”

Efficient public transit systems are also extremely effective at easing congestion on city streets and highways, thereby decreasing the amount of vehicles idling in traffic. The Winnipeg-based Climate Change Connection explains it this way:

“During rush hour in Winnipeg, there is an average of 1.2 persons per car. At that rate, 100 cars and 550 meters of traffic lane are required to accommodate 120 people. Only 2 buses and 25 meters of traffic lane can do the same job, reducing congestion, noise and greenhouse gas emissions by over 90%.”

And from a rider’s perspective, taking the bus or train cuts down on the cost of fuel and vehicle maintenance, making it a viable way to save money. It also makes for a more enjoyable trip across town. Ask anyone who’s rolled past bumper-to-bumper traffic in the bus lane while reading a book or taking a nap.

Just another day on 1st Avenue in downtown Seattle. Photo by Oran Viriyinci

These benefits are already catching on in some of our nation’s more congested cities, and Seattle is a prime example. After pouring billions of dollars into expanding its light rail and bus systems, the city has seen a steady increase in ridership over the last ten years. It’s been called “America’s Bus-Lovingest Town”, and according to the Seattle Business Magazine, nearly twice as many people are now taking public transit to work than are driving alone.

But we don’t all live in cities, and as the American Public Transportation Association points out: roughly 45 percent of Americans have no access to public transportation.

So a key challenge for smaller towns and rural communities today is not just building and implementing public transit systems. It’s getting people to recognize, appreciate and use a system that they’ve never had before — one that is directly at odds with our Cadillac culture.

Incentivizing public transit in the Columbia River Gorge and beyond

Columbia Area Transit (CAT) is one of the many local transportation districts in the region that is meeting this challenge head-on. Formally known as the Hood River County Transportation District, CAT has has been providing public transit services in the county since 1993. In recent years, however, those services have expanded in a big way.

Up until 2017, the local bus functioned as a Dial-a-Ride system, and people wanting to ride the bus had to call and make reservations ahead of time.

Today, CAT has three fixed routes serving different parts of the Gorge. There is the Hood River City route, which stops at 13 different places in Hood River and runs on weekdays until 8pm. There’s the Upper Valley and Gorge-to-Mountain routes connecting Hood River to the upper valley and Mt. Hood Meadows. And there’s the Columbia Gorge Express route, which connects the Dalles to Portland with stops in Hood River, Cascade Locks, Multnomah Falls and Troutdale. (The Columbia Gorge Express was traditionally run by ODOT, but CAT took over the route in November of last year.)

Hood River resident Dillon Simmons uses the Columbia Gorge Express on a daily basis, taking the morning bus to get to work in Troutdale and returning home by bus in the evening. Photo by Jurgen Hess

Leanne Hogie serves as the Board Chair of CAT, and she explains that a number of factors have spurred the district’s recent growth spurt. One is the growing population of the Gorge, and the consequent increase in private cars and parking issues. She also points to the steady growth in tourist traffic, and notes that one of the best features of the Columbia Gorge Express is that it connects with some of the more popular trailheads and recreational communities in the Gorge.

“We thought there were a lot of different things coming together that might make this the time for public transit to really take off,” Hogie says.

Another factor that helped the CAT bus “take off” in recent years, she says, was the Oregon legislature’s creation of the State Transportation Improvement Fund in 2017, which provides an entirely new source of funding for transportation districts in the state.

“That [fund] is making a huge difference for us,” Hogie explains. “It’s adding about half a million dollars annually to our transportation budget.”

That money allowed CAT to buy the buses and hire the drivers that are key to its new fixed route systems. But it didn’t actually get people to ride those buses, and Hogie says that’s been the district’s biggest hurdle over the past couple of years.

“It’s a cultural shift,” she says. “We’re in a place where many people grew up and they never used public transit.”

So in an effort to incentivize public transit, the transportation district made a big announcement earlier this month and rolled out the annual GOrge pass. For the introductory prices of $30 (for adults) and $15 (for children 17 and under), pass-holders get unlimited rides on CAT’s fixed routes through the end of 2020.

(These prices are available until May 18. Click here to learn more about the GOrge pass or to buy a pass online.)

When you consider that it costs a little over $5 (taking into account the cost of fuel alone) to drive from Hood River to Portland in a 2020 Subaru Outback, $30 for unlimited round-trips starts to look pretty appealing. Which is exactly the point, Hogie says.

[perfectpullquote align=”full” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]“We want to remove the financial impediment as much as possible because we really want to get riders on this bus. The more people we get on this bus, the better it is for us, and the better it is for the environment.”[/perfectpullquote]

And looking beyond the Columbia River Gorge, it seems that a growing number of Northwest cities and towns are having success increasing bus ridership using similar incentives.

Olympia’s Intercity Transit took it one step further and got rid of fares entirely at the beginning of 2020. Now, instead of paying $1.25 for local routes and $3 for a ride to Lakewood or Tacoma, anyone can ride the bus for free. (Well, sort of. Funding for the bus system actually comes from an increase in the local sales tax that Thurston County voters approved in 2018. Which means that passengers are essentially paying for their bus fares when shopping.)

The buses on Camano and Whidbey Islands are also fareless, as is the City of Missoula’s Mountain Line — it’s been that way since 2015. But it was another college town that really paved the way, proving that the right incentives can go a long way in getting more people to take the bus instead of driving their own cars.

The Corvallis Transit System (CTS) went fareless on Feb. 1, 2011, and the effects were almost immediate: ridership increased by nearly 38% over the next 12 months.

As Corvallis’ Transit Coordinator Tim Bates explains: “The impetus for this was the Corvallis Sustainability Coalition, which was looking for ways to reduce our carbon footprint and operate more sustainably.”

“One of the suggestions was to get more people on the bus, which led to this idea that the biggest incentive for doing that would be to eliminate fares,” Bates continues.

Corvallis was able to achieve this by enacting a Transportation Operating Fee, which raises the the monthly charge for the City’s utility customers and serves as the funding mechanism that allows for fareless transportation.

Strolling past a bus stop in downtown Portland. Photo by Ian Sane

In the years since, CTS has also used money from the State Transportation Improvement Fund to expand its service area. Bates says this “windfall of money” has allowed them to grow their system by roughly 30% over the last two years, which means the buses can now start earlier and run later.

But looking back on when the City of Corvallis implemented the Transportation Operating Fee in 2011, he recalls that the most common complaint they received was from people who didn’t want to pay a monthly fee for a transit service they never planned to use.

“So, our response was — and would still be now— that even if you don’t use it, it means less cars on the road and less fighting for parking spaces downtown. It’s also reducing our carbon footprint and helping the climate,” Bates says.

“And now, if you fast forward nine years…it’s just wildly popular. We’ve heard from social services people who could not do without it, and the same from lower income people. Even people who have sold their car and are going completely car free, they can do that with a fare-free system.”

Of course, going car-free might not be an option for many of us at this point. But having access to a dependable and affordable public transit system at least gives us the freedom to choose. And isn’t that what America’s all about?

Well, that and…Cadillacs.

*This is the first in a series of stories about the role of transportation in combatting climate change.

Thanks susan. A real education for me, and upping the probability of riding the buses in the future. GOtta go

buy that annual pass.

Great overview of the actual energy requirements of transportation. You may want to consider the true total cost of driving when doing the comparison, including depreciation, amortization, maintenance plus fuel, by factoring those costs, a round trip from Hood River to Portland will be closer to $50 for the most economical car. Even extending this to hybrids and electrics, it is impossible to make the round trip for less than $30.