Photo courtesy of River Drifters

A land sale proposed by Weyerhaeuser exposes the divide between two Wild and Scenic River advocates, private landowners, and federal river managers on the White Salmon River.

By Dac Collins. Nov. 28, 2019. If you paddle boats in whitewater, you will inevitably experience moments when tunnel vision sets in and living in the present is unavoidable. Moments when your field of vision narrows and your grip on the paddle tightens as you commit to a drop borne of water, rock and gravity.

It’s only after your boat crashes through the hole, seething with energy and spraying water in your eyes, that your surroundings re-appear. The trees, the shoreline and the sky come back into focus, and the ecstasy of living in the moment is replaced by the dull sense of self-awareness — the mind’s usual flitting between past and future — that permeates our day-to-day.

It’s no wonder, then, that so many of us return to the river again and again, paddling toward the brief escape into the present waiting at the next horizon line.

There is a danger, though, in succumbing to the hypnotic forces of moving water without occasionally taking the time to look around. Experiencing a river is one thing, but knowing a river and caring for it requires us to look beyond the confines of its banks to the tributary creeks, seeps and springs…the cliffs, trees, organisms and upland areas that are just as much a part of the river as the stream of cold water that shows up as a squiggly blue line on a map.

Wild and Scenic “in name only”

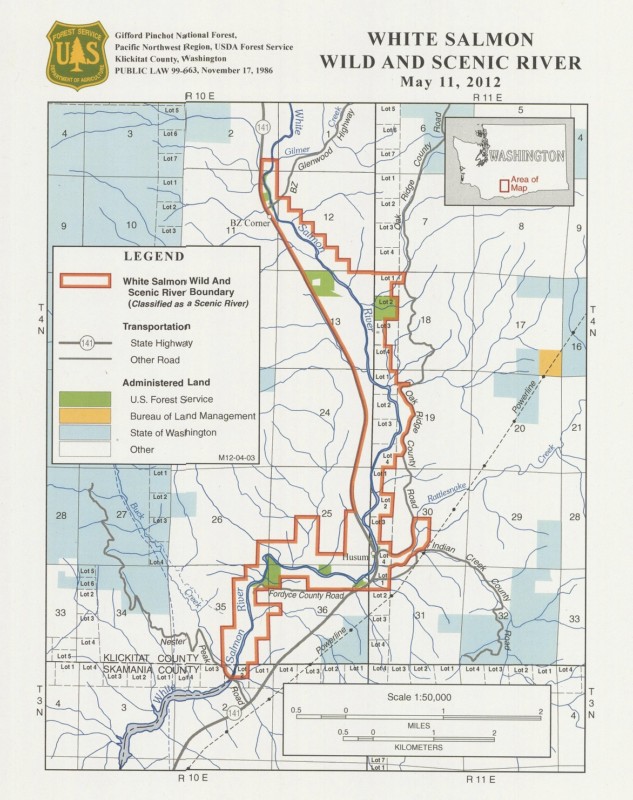

The White Salmon River is one of only three congressionally designated Wild and Scenic Rivers in the state of Washington. A 7.7 mile segment of the White Salmon (from Gilmer Creek at river mile 12.7 to Buck Creek at river mile 5) was brought into the National Wild and Scenic River System in 1986, after it was determined that this stretch possessed the following “outstandingly remarkable values”: whitewater boating, cultural resources, resident fisheries, hydrology and geology.

Many residents of the White Salmon River Valley — along with other proponents of healthy, free-flowing rivers — viewed this designation in a positive light, as the Wild and Scenic River System was established 18 years prior in order “to preserve certain rivers with outstanding natural, cultural and recreational values in a free-flowing condition for the enjoyment of present and future generations.”

Today, the White Salmon is still recognized as a hydrological wonder and whitewater mecca in the Northwest. Meltwater from glaciers on Mt. Adams, combined with a plethora of natural springs, provide in-stream flows that are consistent enough to paddle year-round. (It’s estimated that roughly 25,000 boaters use the river each year.) The breaching of Condit Dam in 2011 also brought national attention the river, as it opened up a new stretch for paddlers, and allowed salmon and steelhead to return to upriver areas that were inaccessible for nearly a century.

In an era when most of our nation’s rivers have either been dammed, diked, polluted, over-allocated or mistreated, the White Salmon River is still in a class of its own.

A summer steelhead jumps Husum Falls on the White Salmon River. Photo by Jurgen Hess

But two of the White Salmon’s longtime champions will tell you that the river is still in jeopardy. They say that due to a combination of corporate greed, increasing demand for residential development and a history of mismanagement by a federal agency, the White Salmon River has become Wild and Scenic “in name only”.

Dave Thies, president of the Columbia Gorge Audubon Society, and Dennis White, the Society’s Washington Conservation Chair, have fought for the protection of the White Salmon River for over 30 years now. White, along with his wife, Bonnie, and other residents of the Trout Lake Valley, founded Friends of the White Salmon in 1976 when the river was being threatened by hydropower development. And he was directly involved with efforts to add the White Salmon River — and also the nearby Klickitat River — to the National Wild and Scenic River System.

Securing that designation, though, was only the first in a series of contentious battles over how the river and its surrounding forests should be managed. Over the course of the last few decades, Thies and White have squabbled with developers and timber companies, as well as the US Forest Service, the federal agency that was chosen by Congress to manage the Wild and Scenic River.

“We’ve earned our reputation. And there’s a lot of opinions about us out there, some of which aren’t very nice,” says the soft-spoken Thies, a White Salmon resident who takes pride in having worked in nearly every phase of the wood product industry. “I’ve been a logger and a carpenter, and I’ve worked in tree nurseries and sawmills,” he continues.

Thies has also, at times, resorted to using his imposing 6’ 3” frame as an obstacle. He and White recall a battle in the late 1980’s over a tract of privately owned forest surrounding Spring Creek, which falls within the federally protected Wild and Scenic Corridor. The creek is one of the major fish-bearing tributaries of the White Salmon, and it flows through an area where the Forest Service was (at one point) planning to develop hiking trails and a picnic area. But the land was — and still is — owned by SDS, and the timber company intended to log the second-growth forest, just as it had done with many of its other holdings scattered throughout the White Salmon Valley.

So White and Thies dug their heels in. They picketed the Heathman Hotel in Portland, which, at the time, was owned by a member of the Stevenson family, and they formed a blockade against the logging trucks.

“We stopped that logging operation,” White says. “After we stopped it, the Forest Service wrote them a letter saying, ‘you can’t do that.’”

[perfectpullquote align=”full” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]“Then a few years later, guess what? They came back in and logged the hell out of it.”[/perfectpullquote]

The logging that occurred around Spring Creek, which White calls the “crown jewel” of the Wild and Scenic White Salmon, is at the heart of his and Thies’ frustration with how the river has been managed over the years.

The Weyerhaeuser tract

Their most recent campaign involves another timber company: Weyerhaeuser, which is one of the world’s largest private landowners with over 12 million acres of commercial timberland in the United States. The publicly-traded corporation has always been a big name in the state (and especially in southwest Washington), but its presence in the White Salmon Valley increased substantially when, in 2013, it purchased Longview Fiber for $2.6 billion and acquired roughly 645,000 acres in the Mid-Columbia Region.

Weyerhaeuser is now attempting to sell off some of that land, including 240 acres located on the east side of the river. This acreage can be accessed via Oak Ridge Road, and it neighbors the property where the Whites have lived since 1979.

Weyerhaeuser has divided the 240 acres into three 80-acre tracts, and one of those tracts is currently listed with Copper West for $339,000. Of those 80 acres, 30 of them fall within the present boundary of the Wild and Scenic Corridor. The tract also straddles the White Salmon River, with a small chunk of it located on the river’s west bank.

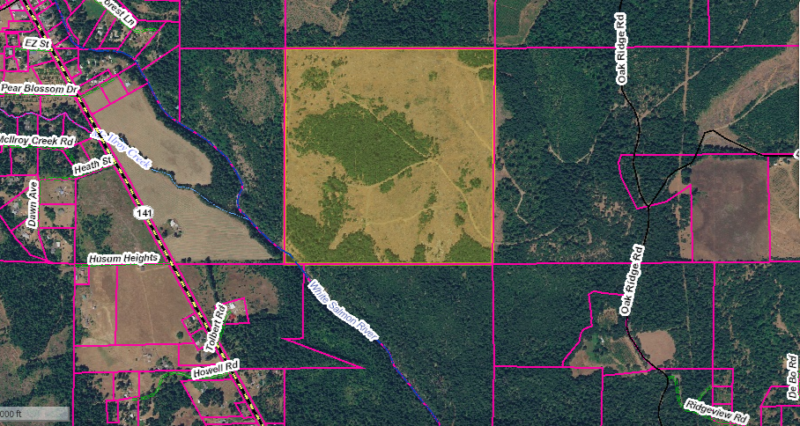

The highlighted 160-acre tract, owned by Weyerhaeuser, has been divided into two 80-acre tracts, both of which are currently listed for sale. Map courtesy of Klickitat County

White brought the land sale to the attention of the Forest Service’s National Scenic Area Office this summer, as he believes the sale would lead to residential development on the property, which could threaten the overall health of the Wild and Scenic River Corridor. He is hoping the Forest Service will acquire the land, and has been in contact with the agency and the Weyerhaeuser Corporation in an effort to broker some sort of deal.

“We’re up against a big timber corporation that wants to sell off these lands for residential development,” he says. “First you have to get the Forest Service to even consider buying it. Then you gotta get Weyerhaeuser to agree to sell it to them at fair market value. And that’s a big leap.”

White and Thies view residential development as the worst possible use for this land. They say that aside from impacting wildlife habitat, and affecting the aesthetics and rural character of the Wild and Scenic Corridor, the development would require a number of wells to be drilled, which could impact the water table and potentially threaten one of the river’s outstandingly remarkable values: hydrology.

“This Weyerhaeuser property is full of springs that flow into the White Salmon River. Once the infrastructure is in there for housing development, each house will be on a permit-exempt well,” White explains. “And all those wells will be drawing down the water table”

Pat Arnold is the chair of the board of Friends of the White Salmon, and she echoes White’s concerns, saying, “All of this development really does damage the hydrology of the river. Everybody that drills a well drills into that shallow aquifer, and that’s where all those springs and seeps are coming from. And the springs and seeps are a very important part of the life of the White Salmon.”

She points to areas where wells have already been drilled close to the river, like the castle located on the east bank of the river south of Husum, and the newly constructed homes located north of Husum between the river and Highway 141.

“Trees grow back, but once the houses come in it’s lost,” Thies adds.

Satellite imagery of the area shows that Weyerhaeuser’s property has already been clearcut. The timber company did leave some Oregon white oaks on the property.

Weyerhaeuser declined to comment for this story, as did the listing agent for Copper West who is representing Weyerhaeuser in the sale.

Rachel Pawlitz, the Public Affairs Officer for the Columbia River Gorge National Scenic Area (CRGNSA), says, “We have the authority to acquire some more lands within the Wild and Scenic Corridor, and were asked to potentially intervene in that [land sale]. So we entered into talks with the seller, and at the last update that I got, we were still in conversation.”

“Essentially,” Pawlitz says, “we have some tentative interest in acquiring particularly the part that’s inside the river boundary. However, it’s highly unlikely that we would acquire and in any long-term way maintain the full parcel.”

White sees this “tentative interest” as a positive development, but says that due to the troubled history of federal land acquisition within the Wild and Scenic Corridor, he’s not holding his breath.

The pitfalls of private land

Almost all of the Wild and Scenic Rivers in the American West are located on public land. Rivers like the Rogue, the Deschutes, the Flathead, the John Day and the Salmon are all surrounded by federally owned lands, with most of these lands falling under the purview of the Bureau of Land Management (BLM). So when the Management Plans for these rivers were drafted, the BLM became the de-facto agency responsible for implementing the plans and enforcing the protections that were, essentially, put in place by Congress.

The White Salmon, on the other hand, was surrounded entirely by private lands when the 7.7 mile stretch of the lower river was originally designated in ‘86. This made drafting a Management Plan for the river significantly more challenging and complex.

It was decided early on that because of the river’s proximity to the Columbia River Gorge National Scenic Area, the US Forest Service would be the federal agency tasked with managing the Wild and Scenic waterway. The agency then began studying the river, and after seeking input from Klickitat and Skamania Counties, Washington State, the Yakama Nation, local residents and private landowners, the agency drafted a Record of Decision for the National Wild and Scenic River Management Plan in November of 1991.

The Forest Service then adopted boundaries for the Wild and Scenic River Corridor, which, according to the Record of Decision itself, was a contentious process:

“The planning team was challenged to strike a balance between adequately protecting and enhancing the river by maintaining the current character of the river area and providing long-term protection and enhancement of its outstandingly remarkable values, without unduly limiting other uses, including private lands, that do not substantially interfere with public use and enjoyment of the river’s values.”

Thies says that federal and state wildlife agencies initially pressed the agency to incorporate the maximum amount of acreage allowed by the Wild and Scenic River Act — “an average of not more than 320 acres per mile on both sides of the river” — while others urged the Forest Service to constrict the corridor according to Washington State’s Shoreline Management Act, which provides a continuous buffer of 200 feet from the river’s shoreline. The Forest Service eventually adopted Alternative 6, which brought 1,874 acres into the Wild and Scenic Corridor — an average of 244 acres per river mile.

This map shows the current boundaries of the Wild and Scenic Corridor. Photo courtesy of the USFS

It’s important to keep in mind that all of this acreage was privately owned at the time. So the Forest Service came up with a plan that would bring more of this land into public ownership.

Pawlitz explains that at the heart of this plan was a three-way land exchange between SDS, the Washington Department of Natural Resources and the agency itself.

According to the Record of Decision: “A key decision is that the Federal government will acquire, through exchange, all lands within the boundary owned by SDS Lumber Company. This is more than 700 acres, amounting to almost 40% of the land within the boundary.”

But SDS backed out, and the land exchange never happened. Today, the Lumber Company still owns approximately 40 percent of all lands within the boundary. And in the time since the land exchange fell through, the Forest Service has acquired a total of 144 acres (or roughly 13 percent of the lands within the boundary) out of a potential 770 acres.

Casey Andrews is the Wild and Scenic River Coordinator for the CRGNSA, and she explains that, according to the Wild and Scenic River Act, “We’re only allowed to acquire 100 acres per river mile, and that would give us 770 acres that we could acquire.”

Pawlitz adds that the Management Plan “calls for us to work on a willing basis with sellers,” which means the agency has always avoided condemnation as a strategy for acquiring private lands.

According to the Record of Decision: “The Forest Service will not use condemnation to acquire scenic easements on, or fee title to, private lands unless that is necessary, as a last resort after all other measures have failed, and then only to prevent imminent, serious adverse effects to the river area.”

Pawlitz also explains that the Forest Service is not the sole authority in the valley. She says the agency is required to work hand-in-glove with Klickitat and Skamania Counties, as well as the State of Washington, when dealing with privately owned lands that fall within the Wild and Scenic River Corridor.

“The key here is that it’s a state, local and federal partnership,” Pawlitz says.

And according to Andrews, “It seems to be a common misunderstanding that we have the authority to regulate on private land along the river. Anything that is not the river itself, we monitor from the river. That’s the only legal place that we can monitor because we don’t have jurisdiction to go on the land.”

Andrews and Pawlitz say the CRGNSA Office is directing its limited resources toward monitoring activities on the river itself, and the agency runs an outfitter program that issues special use permits for commercial rafting trips down the iconic Wild and Scenic stretch.

As for purchasing private lands adjacent to the river, Pawlitz says they have a priority list of properties they’d like to acquire. At the top of that list is Northwestern Park, which is located at the southern terminus of the Wild and Scenic stretch (and is currently owned by PacifiCorp.) The park is a popular river access for rafters and kayakers, and it would be the third public river access acquired by the agency within the Wild and Scenic Corridor. The other two sites are located at BZ Corner and Husum Falls.

Rafters with Wet Planet get a taste of Husum Falls. Photo by Jurgen Hess

“We also have to work within our budget,” Pawlitz says, “and we recognize that there’s a balance between community needs, private landowners and the White Salmon River. The federal role primarily is to protect the river’s free-flowing character and the outstandingly remarkable values.”

Funding: the other F-word

For Thies and White, the controversy surrounding the Weyerhaeuser property is merely a symptom of a much larger problem: that the Forest Service has been either unable or unwilling to acquire enough private land to properly manage the Wild and Scenic River Corridor.

They also bring up the fact that in 28 years, the agency has never updated its Management Plan, even though the initial Record of Decision from ‘91 explicitly states that “the Plan will be revised no later than 15 years from the date of this Record of Decision.”

“The only way the Forest Service can implement their Management Plan is through land acquisition, fee title or conservation easements. With that in mind, they have failed miserably in acquiring necessary fee title lands and easements,” White says.

“Their record speaks for itself. 144 acres in almost 30 years, and not a single conservation easement.”

He says the management situation is even worse on the Klickitat River, where the Forest Service has only acquired one parcel of land that is within the Wild and Scenic Corridor but outside of the Scenic Area boundary.

Getting back to the White Salmon, though, Thies says he is still holding out hope that Weyerhaeuser will “do the right thing” and donate or sell the land to the Forest Service. He points to the corporation’s website, which states:

“We recognize that some lands have special value to the people who live in communities surrounding them. Respecting that, we seek opportunities to protect areas that have exceptional historic, visual, recreational, forestry or wildlife habitat attributes. We work with organizations like the Nature Conservancy, the Trust for Public Land and other environmental, recreational and wildlife organizations to complete conservation transactions. These transactions include conservation sales, conservation easements, land exchanges and the transfer of development rights.”

“If Weyerhaeuser were to say: ‘We really might be interested in bringing this property into public ownership, and we have already stated that we like to save special lands for communities.’ If they did that, well the Forest Service would have to start thinking about stepping up a little bit more. And conversely, if the Forest Service would say, publicly, ‘we’re interested,’ that would put Weyerhaeuser on the spot. But, so far, neither of them really want to go there,” Thies says.

Looking upstream at the confluence of Spring Creek and the White Salmon River. Photo by Dac Collins

One thing that the Forest Service, Thies and White can all agree on, however, is that an overall lack of funding lies at the root of these management concerns. White explains that since the CRGNSA Office is charged primarily with managing lands within the National Scenic Area, it is difficult for the agency to set aside enough funds for the Klickitat and White Salmon Rivers, which lie outside the boundaries of the Scenic Area.

“The problem is that because the Columbia River Gorge National Scenic Area is there, and because it’s big and it has a lot of needs, all the money goes there. And the Wild and Scenic Rivers just starve to death,” White says.

Arnold has noticed the same underlying problem during her tenure as executive director of Friends of the White Salmon:

[perfectpullquote align=”full” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]“There’s many, many political currents that make these things go the way they go. And part of it is just the dearth of public funding.”[/perfectpullquote]

“Any Forest Service acquisition that can happen at this point is a good thing,” Arnold says. “A purchase would hopefully begin to get a ball rolling. And then there needs to be enough pressure coming from this direction saying, ‘This is important, this funding needs to happen, these purchases need to happen.’ And unfortunately, the way you do that is you show people how bad it’s getting, which is not too hard to do anymore.”

“It’s a real quandary for us,” White says. “What do we do? Just sit back and watch the degradation of the river corridor, or do we make it public and say, ‘Hey, this is what’s going on, people.’”

Nice piece of writing, Dac. I got hooked into the full read by your point about the present moment.

Well done, Dac. Great job digging into this complicated situation and reflecting the sense of urgency we feel about protecting the Wild and Scenic White Salmon and Klickitat rivers. One small correction. I am the chair of the board of the Friends of the White Salmon River, not the executive director.

Thanks, Pat. The correction has been made.

Thanks so much. Was not aware of the problem prior to your excellent story.

Five themes became evident in the Forest Service quotes for this story: to balance protection and private land use; to limit management to “the river area”; there will be no condemnation; there will be no monitoring, except for river use; and the focus of these acquisitions will be limited to facilitating whitewater recreation. The Forest service has used these themes to subvert the legal requirements of the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act for the White Salmon and Klickitat National Wild and Scenic Rivers.

The agency’s focus on “the river area” alone has served as a signal to SDS and developers that all of the private land that is not in the river area is open to clear-cut logging and residential development. Over the years it has become apparent that this “river area” actually means the river itself (between the confines of its banks) and a few trees overhanging the river canyon — which is only a percentage of the overall management corridor that was designated by Congress in 1986.

This tunnel vision management style of the river corridor is why so many clear-cuts have occurred, and it explains why residential development has been an ongoing problem — and is now becoming an even greater threat in both the riparian and upland areas of the management corridor. If this mismanagement and neglect is allowed to continue, the Forest Service will eventually use the very damage that is currently befalling the ORVs as the reason for limiting the Wild and Scenic River Boundaries to the river area. In fact, I believe that has been their plan all along.

At the center of this story is the Weyerhauser property that is now for sale. In the story, the Forest Service says, “We were asked to intervene in that [land sale]…and we have some tentative interest in acquiring particularly the part that’s inside the river boundary.”

For the record, Columbia Gorge Audubon Society asked them to intervene in that land sale, and the Forest Service apparently had no knowledge of it until we brought it to their attention. The Forest Service should have more than a “tentative interest” in this land. It has already been clear-cut of marketable trees, and the land is being marketed for residential development.

In the time since this story was published, Columbia Gorge Audubon Society has requested that our U.S. Senators and Representatives investigate blatant Forest Service neglect and mismanagement of the White Salmon and Klickitat National Wild and Scenic Rivers.

In conclusion, it is a little-known fact that when Congress was considering the creation of the Columbia River Gorge National Scenic Area, the Forest Service tried to avoid becoming the lead management agency of the NSA (and the adjoining Wild and Scenic Rivers). We believe that they knew from the outset that they were not the right agency for the job. The agency with the traditions and management style to do the job right is the U.S. Park Service, and that is the agency we recommend to take over the management of our National Wild and Scenic Rivers.

After wading through all the agencies mentioned in this article that affect what may happen to this extremely unique river habitat, “the dearth of public funding” mentioned by Arnold, is probably the main reason why more can’t be done to protect the area. It would seem to me that an agency like the Nature Conservancy would be willing to pay a substantial sum to acquire such a pristine asset. Is enough being done to convince the Conservancy? Is Weyerhaeuser the only entity going after their money?