This is Part 1 of Impervious, an Envirogorge series on transportation. Writer Valerie Brown explores what it takes to create ease of movement in the Columbia River Gorge. SEH & EKK

You’re on a home improvement kick. You pour a new concrete driveway, put on a new roof black asphalt shingles, clean your rain gutters making sure the downspouts feed into the stormwater drains, spray Roundup on the weeds in the seams, then seal the concrete.

Unfortunately this way of imposing order on the chaos of nature and human habitation has a downside for vital human and ecosystem resources: water and soils. By covering your property with hard surfaces you’re interrupting the natural water management system. In the Gorge this adds insult to injury because the beautiful landscape is underlain and shaped by the Columbia River Basalt.

Rain falling on the cliffs along Interstate 84 “will just run off into the Columbia without much resistance,” says Bill Mason, a hydrologist with the Oregon Department of Environmental Quality, because basalt resists erosion. The few areas flat enough to be floodplains that could accumulate sediment and create topsoil are often overlain by gravel, sands and silt swept down the river in the massive post-glacial Missoula floods. Thus laying down impervious surfaces further obstructs a geological landscape that was already quick to release water into the river.

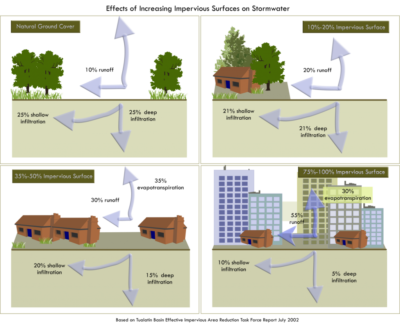

In a landscape unaltered by humans, water percolating through rocks, sand and soil is cleaned and delivered downstream slowly. In general, only about ten percent of rain turns into immediate runoff. But an urban landscape that’s 75% impervious turns more than half of its precipitation into runoff immediately. The sheer volume of water moving faster than normal erodes streambeds and banks and moves vast quantities of sediment downstream.

Read Part II of our Impervious series?