By Dac Collins. April 25, 2019. It’s no coincidence that Oregon’s most contaminated (and endangered) river happens to flow through its three most populated cities. Proximity breeds pollution, or so it seems. And aside from the million or more residents of Eugene, Salem and Portland who use or depend on the Willamette in some way, industrial development in the Portland Harbor has been particularly unkind to the river.

Over the course of the 20th century, these shipyards, factories and chemical plants created hundreds of jobs, ushering the port city into a new era of wealth and prosperity. But they left behind a toxic legacy, one that lives on in the surface water, groundwater and sediment of the urban waterway.

Ships fill the Portland Harbor at the turn of the 20th century. Photo courtesy of Wiki Commons

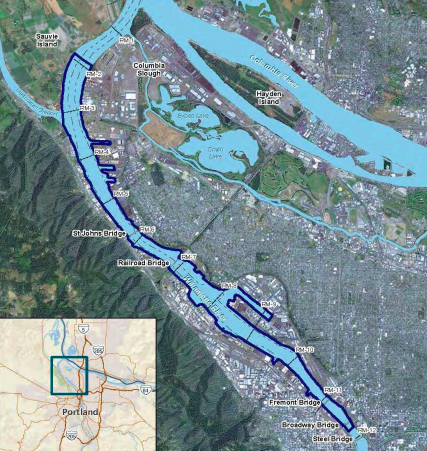

PCB’s, heavy metals, dioxins and mercury…lead, PAH’s, petroleum and pesticides. These and other harmful pollutants have settled at the bottom of the broad, slow-moving river, and they present significant health risks to humans and the environment. They are also the primary reason that the 2,000+ acre, 10 mile stretch of the lower Willamette — from the Broadway Bridge to its confluence with the Columbia — was designated as a Superfund Site in 2000.

17 years later, the Environmental Protection Agency issued its plan to clean up the Site.

Known as the Record of Decision, the agency’s plan lists over 150 companies and agencies as Potentially Responsible Parties (PRPs) — and because Superfund law dictates that polluters are held liable, these parties are responsible for implementing the cleanup and footing the bill. The plan involves dredging millions of cubic yards of sediment, capping large areas of the river bottom and banks, and monitoring other areas as they recover naturally. When completed — which, according to the EPA, will take a decade or more and cost approximately $1 billion — the cleanup will theoretically reduce the human health risks for Portland residents and improve the overall ecological health of the river.

But looking at this costly mess now, in 2019, a couple of questions come to mind…namely: What is the status of the cleanup today? And why does it seem to be taking so long?

Designing the cleanup

Suzanne Skadowski is a public affairs specialist with the EPA’s Region 10 office. She explains that when it comes to a site as large and complex as the Portland Harbor, there is no single solution for the contamination problem. There are instead a number of strategies that work better in certain situations. And because of the dynamic nature of a river, even these strategies can change shape over time.

A general overview of the Superfund Site. Map courtesy of EPA

“That’s part of designing the cleanup,” Skadowski says. “It’s a dynamic system, so you don’t just come up with a plan and then a few years later go for it. What we’ve been doing since we proposed this clean up plan is getting out on the river and in the water and river bottom sediments, and either confirming or updating our earlier data to see what has changed.”

She explains that progress has been made at some of the highly contaminated “hot spots” — also known as “early action cleanup areas” — throughout the 10 miles of river. She points to Rivermile 11 East, where PRPs such as the CBS Corporation, Cargill Inc. and Glacier Northwest Inc. have already come up with a design for how to move cleanup operations forward.

But she acknowledges that “the bigger-picture, long term site wide cleanup designs are still in the works.”

Skadowski says this big-picture plan is guided, in part, by what the agency calls a “community involvement plan”. This living document is the product of years of public engagement and continued interactions between the EPA and local communities.

The Willamette winds its way through Bridgetown. Photo courtesy of the Port of Portland

“We are now re-upping, revising and expanding that community plan,” she says. “We heard from community members that they wanted to sit down with us and have an opportunity to ask questions more often and hear what’s going on. So last week we held one of several quarterly forums with the community to give them the opportunity to come by and ask questions.”

During that forum, which took place at Portland State University on April 17, the EPA provided a general update of the work that is currently being done.

Skadowski says the next public forum is planned for June 12 (location TBD). She says that, in addition to hosting these forums, the EPA will continue to talk and meet with individual community groups and leaders to hear their feedback and concerns.

Cleaning up versus covering up

As the executive director of Willamette Riverkeeper, Travis Williams has been involved with this cleanup process since it began in 2000. And over the course of these 19 years, Williams has learned a lot about politicizing, strategizing and finger-pointing. But perhaps his biggest takeaway from the process is that the act of cleaning something up can be interpreted different ways by different people.

“I think what people too often get lost in is this isn’t really a clean up,” Williams says. “It’s a risk reduction exercise.”

Because of the sheer size and scope of the Superfund Site, it’s easier to look at it as a series of individual sub-sites. Each sub-site has a unique set of problems or health risks, as well as an entity (PRP) who is responsible for solving those problems…or, in Williams’ words, reducing those risks.

A bird’s eye view of the Swan Island industrial area. Photo by Travis Williams

“Right now we’re in a bit of a holding pattern as different entities negotiate with the EPA to move forward at individual sub-sites,” he says. He uses the same example that Skadowski points to when explaining how PRPs like Cargill and CBS (River Mile 11E) are, in a sense, ahead of the curve.

“Then you have others who haven’t really done much,” Williams says. “And they are just kind of…for whatever reason, stalling.”

According to Skadowski, the majority of PRP’s (100+) have yet to initiate any sort of cleanup design. She says the EPA sent out a letter in March of 2018 asking those entities “to organize and step forward to conduct 100% cleanup design for 100% of the site,” but that “as of December 2018, we had gotten no offers to perform cleanup design, only additional sampling and in very small areas.”

This, of course, speaks to why the cleanup process continues to drag on. By filing formal disputes with the EPA or choosing to ignore to the agency’s requests, or by arguing that certain studies have to be repeated, a number of PRPs have ensured that timelines are extended and initial actions are postponed.

Complicating matters further is the fact that, nearly two decades after calling attention to the contamination problem, the EPA is still looking at a variety of different ways to address it.

One way is to dredge huge swaths of the riverbed, which means scooping up the toxic sediment and burying it in a disposal site (usually a permitted landfill) located far away from the river.

Another method is to “cap” the contaminated areas with concrete, gravel or some other material…which, by definition, is more akin to covering up the mess than cleaning it up.

Skadowski, however, explains that the capping process is more complicated, and that “capping can look a little different in different places.”

She says that in certain areas, where natural sedimentation is already covering up some of the contaminated riverbed, “we’re just helping it along.” In other places, though, she says “you might want to have several layers to make sure that you’re putting clean material down and it will stay down to contain the contamination away from river bottom organisms and fish.”

The general idea, Skadowski says, is that organisms living on a river bottom establish themselves on the upper layer of sediment. And “the deeper the [contaminated] sediments are, the better,” she continues, “especially in terms of the organisms that are living and feeding on that sediment.”

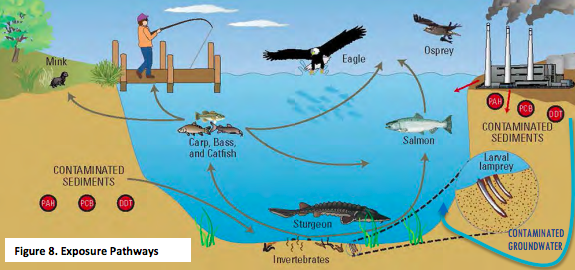

The cycle of contamination affects every link in the food chain. Photo courtesy of EPA

A third strategy is what the EPA calls “monitored natural recovery.” And while it is defined in the Record of Decision as the use of “ongoing, naturally occurring processes to contain, destroy or reduce the bioavailability or toxicity of contaminants in sediment”, it really just amounts to sitting back and taking water samples while the river cleans itself.

Of course this strategy of action by inaction leads to a slippery slope where explanations take the place of implementation. And the proposal that acting EPA administrator Andrew Wheeler put forward last fall is a perfect example of this.

Explaining that the change is meant to “ensure that the cleanup plan is current with the latest science to protect people’s health and the environment,” Wheeler announced in October that the agency is considering reducing the cleanup area around Portland’s Terminal 4 and NW Natural’s Gasco property. The modification of this particular sub-site would cut costs by approximately $35 million, and the “latest science” that Wheeler refers to is the consensus reached by a number of agency officials that benzo(a)pyrene (or BaP) is less risky — or less likely to cause cancer — than they initially thought.

(Skadowski says the agency is still deliberating and reviewing over 1,000 public comments received, and is expecting to issue a final decision on this proposal by the end of the year.)

And while environmental and human-health advocates worry about the implications of this particular announcement, there is more baseline sampling currently being done. One example is looking at the effectiveness of river flow and sedimentation from clean sediments upstream and flood events (like the one that occurred earlier this month) in flushing out and covering up some of the river’s toxic sediments.

A sign at Willamette Cove warns the public of the health hazards of swimming in or recreating near the river. Photo by Travis Williams

“Then the question is to what degree will the EPA make that information available,” Williams says. “Because there is a fear that some people who are sponsoring these baseline studies will come back and say: ‘Well the contamination based on our assessment is less than it was 5 years ago…therefore, the river is already on its way to recovering itself.’”

His concern is if that were to happen, the Record of Decision could open back up and the years-long process of soliciting input from PRPs and formulating a cleanup plan would start all over again.

“If that doesn’t happen,” Williams says, “what we hope to see is that those individual sites that have already come to agreements with the EPA will demonstrate to others that they need to do the same thing. And maybe we will begin to see barges in the water during the next low flow work window.”

[perfectpullquote align=”full” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]“I think what frustrates a lot of people in this process is we haven’t seen much of that yet.”[/perfectpullquote]

The frustrations that Williams and other cleanup advocates feel are warranted, especially when you think about everything else that we as a society have accomplished in the past 19 years.

We’ve witnessed the rise of smartphones, which have revolutionized the ways that people share information and interact with one another. We elected the first black president of the United States and we legalized gay marriage. We saw the first electric sports car hit the market…a model that now seems outdated compared to the spaceships Musk and his team are currently working on.

In the last twelve months alone, a researcher in China created the world’s first genetically edited babies. We also found signs of liquid water on Mars and generated the first ever image of a black hole.

But we’re still working on a plan to clean up the Willamette.

It seems that the EPA is intentionally dragging out the process. EPA needs to be more assertive and force the big PRP’s to get started which could be an example for others to follow.

Very good information on what’s the issue of footdragging and not getting started.