The unexpected finds in Chelan County have important implications for biodiversity and knowledge about expanding ranges

Newby: The scopa on the abdomen of this female bee and its heavily pitted “terga” with inflated edges help to identify it as Dianthidium singulare. Photo: Autumn Maust

By Kiyomi Taguchi/UW News. October 28, 2025. Bee experts wouldn’t have previously expected to find the likes of Osmia cyaneonitens, Dufourea dilatipes and Stelis heronae in Washington. But this year, researchers added eight new bee species to a list of the state’s native pollinators.

While collecting pollinators in Chelan County to study how climate and wildfires affect native bee populations, Autumn Maust, a University of Washington research scientist of biology, discovered eight bee species never recorded in Washington and 100 species that had not previously been documented in Chelan County.

“Six of the eight bees we identified are pollinators,” said Maust. “The other two, Coelioxys funerarius and Stelis heronae, are cleptoparasitic, or ‘cuckoo’ bees, that lay their eggs in the nests of pollen collecting bees.”

The six pollinators identified are likely not new to the state, according to Maust, and instead had not been previously recorded due to under-sampling.

The finds were part of a larger effort undertaken by 67 Washington Bee Atlas volunteers, who collected over 17,000 specimens on more than 600 different host plants.

“While many of these bees have yet to be identified, there have already been several remarkable discoveries, including a bee which had not been recorded in the state since 1917 and one that had never been found in Western Washington, in addition to 15 species which had never been collected in the state before,” according to the Washington State Department of Agriculture.

Expert taxonomists from Utah to British Columbia helped Maust identify the bees, which were photographed in high resolution for her research.

“It’s a really exciting moment. Sitting with an expert taxonomist to determine the identity of an undocumented bee filled me with awe,” said Maust, who completed this research as a UW doctoral student of environmental and forest sciences. “They cited subtle characteristics that I would not have even known to examine.

“The findings also have important implications for biodiversity. It’s difficult to conserve a species when we don’t know its name or native range.”

Collect calling: Autumn Maust conducting fieldwork near Mount Rainier. Photo: UW News

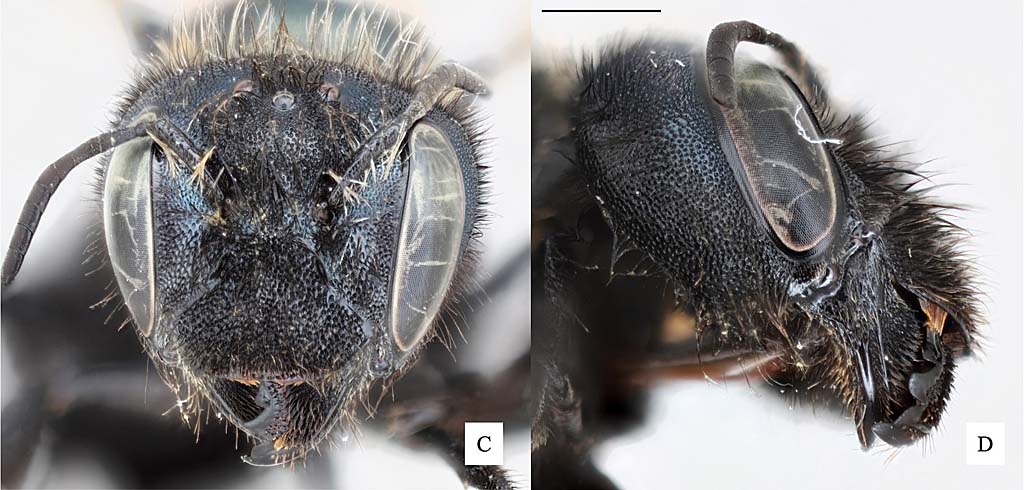

Taxonomists refer to detailed sets of characteristics to differentiate bees by family, genera and species.

The morphological qualities of bees are incredibly diverse, and individual species can vary in small but significant ways.

Bees can be distinguished from each other by the shape and structure of wing veins, hair color on the “terga”—plates forming the bee’s abdomen—and the location of “scopa,” or pollen carrying hairs.

“This work highlights the importance of targeted bee research in understudied regions of the state,” she said. “Such work would allow conservationists to have a complete understanding of regional bee populations, particularly in light of globally and regionally documented bee declines.”

If you’re interested in bees, Maust said, the Washington Bee Atlas trains volunteers to find, collect and identify native bees. Individuals can also share bee photos and observations on sites like iNauralist where the data is made available to researchers.

Depicted below are two of the new-to-Washington bees Maust observed and the characteristics scientists focused on for classification.

This fierce-looking female Osmia cyaneonitens has huge mandibles (teeth) and flashy blue coloring. Osmia, in the mason bee family, use their large mandibles to move mud or cut leaves or petals to build nests. Their bodies are often metallic blue and green. Photo: Joel Gardner/WSU

This Dufourea dilatipes Maust collected belongs to a rare group of the Halictidae family, commonly called “sweat bees” because they’re attracted to the salt and moisture in the sweat of mammals. All members of this family have a strongly arched basal vein on the forewing. Dufourea dilatipes exclusively forages on Calochortus flowers for pollen and nectar. Photo: Josh Milnes/WSDA [An earlier version of this photo incorrectly identified the position of the basal vein. —Editor]