Wolves, water, wildfire. Extremes kept on getting more extreme

By Chuck Thompson. December 26, 2023. In May, Aja DeCoteau, a citizen of the Yakama Nation, became the first Native American to serve on the National Park System Advisory Board.

In July, a cougar was spotted on Haystack Rock at the Oregon Coast.

In December, Washington purchased 20,000 acres of logging lands west of Longview, the state’s largest timberland acquisition in more than a decade.

And this photo of the Tunnel 5 Fire in the Columbia River Gorge taken by Columbia Insight board member and in-house photographer Jurgen Hess was chosen as a finalist in the Professional Photographers of America’s International Photographic Competition (winners will be announced in January).

Important events, for sure, but each was edged out by 10 others on our annual list of the year’s biggest environmental stories.

Photo: WDFW

No matter the month, wolves made news. In April, Washington biologists confirmed the existence of a wolf pack on the western flank of Mount Spokane. In July and August, Oregon wildlife officials killed six gray wolves in eastern Oregon—after preying on livestock, the wolves were caught with foothold traps then shot by U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Wildlife Services staff. In November, conservation groups filed a petition to stop the U.S. Forest Service from hunting wolves from helicopters in Idaho, and Washington’s Klickitat County Sheriff Bob Songer ginned up fears by claiming wolves were being introduced into his county (they aren’t). In spite of the agitation, wolves continue to rebound—in December five wolves captured in Oregon were released into the wilds of Colorado as part of that state’s recovery program.

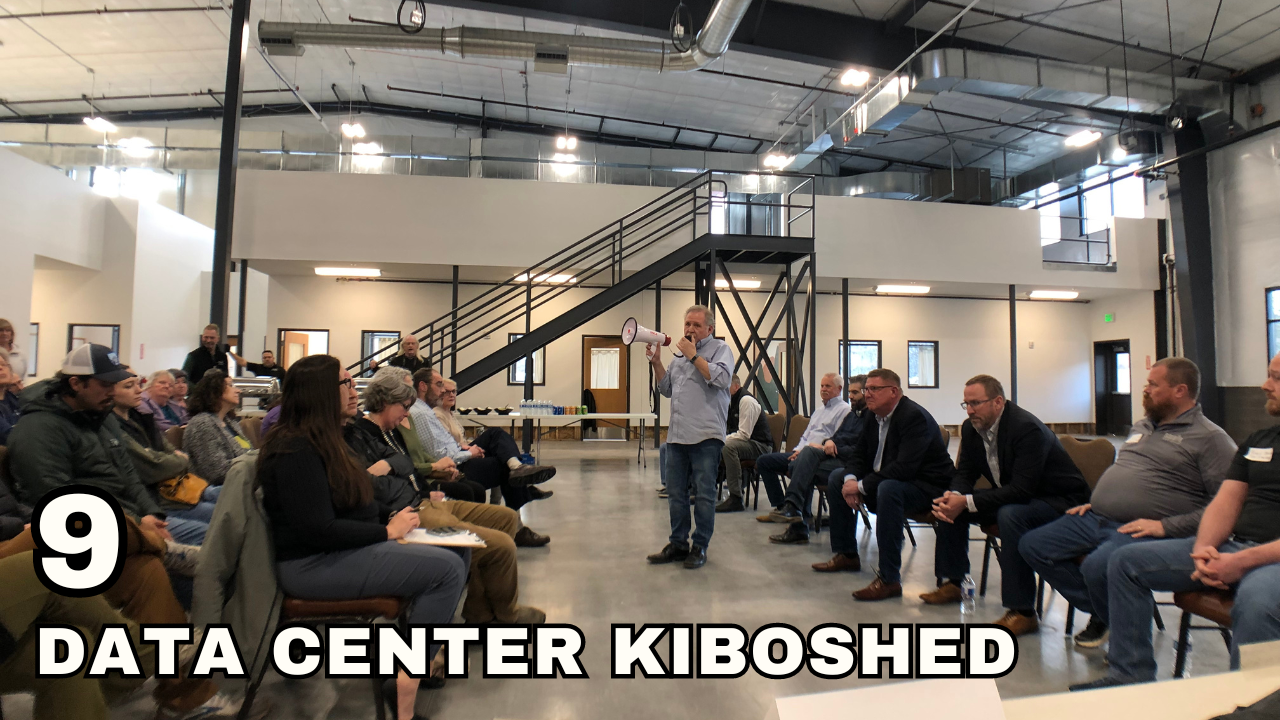

Roundhouse CEO Stephen D. King addresses Cascade Locks residents. Photo Nathan Gilles

In March, Columbia Insight reported on a $100 million data center proposed by a startup company called Roundhouse in the Columbia River Gorge town of Cascade Locks, Ore. Many locals expressed concerns about the company, the checkered past of its CEO Stephen D. King and the financial and environmental impacts of the data center set on the banks of the Columbia River. In July, after intense local pushback, the Port of Cascade Locks and Roundhouse jointly announced the decision to discontinue the project.

Photo: Quagga mussels. Photo: Andrea Miehls/USGS

In October, the Idaho State Department of Agriculture launched a comprehensive treatment plan to eradicate invasive quagga mussels from the Snake River, first detected near Twin Falls in September. “If nothing were done, quagga mussels would quickly take over waterways. They would irreparably harm water use in Idaho,” said the ISDA. The obliteration effort involved dumping a highly toxic chelated copper product called Natrix into the river that was expected to kill most of aquatic life, plants and fish along a six-mile stretch of water. “The Snake River is Idaho’s lifeblood, and we are doing everything we can to eradicate quagga mussels from our waters,” said Idaho Gov. Brad Little. Officials won’t know if the $3 million purge was successful until spring, when water warms up and sampling surveys resume.

Photo: Saddle Mountain, Oreon. Photo: Richard Felley

In August, the extent of the past two decades of clear-cutting in the Oregon Coast Range was revealed in a report produced by nonprofit Oregon Wild and NASA DEVELOP. The cuts, which remove vital forest canopies, have had a detrimental effect on drinking water across 80 watersheds along the coast. “Logging operations are widespread across the Oregon Coast Range and conventional logging practices pose a risk of contamination to surface water quality,” according to the report summary.

Fire suppression practice, Yakima Training Center. Photo: U.S. Army

Popularly known as “forever chemicals” or “PFAS,” per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances have been in commercial production since the 1950s. They’re everywhere, including in our water, clothes and cookware. But concerns about their link to health risks—including kidney and testicular cancer, hormone disruption, liver and thyroid problems and abnormal fetal development—exploded this year after major exposés in national media including The Washington Post. Regionally, outlets such as the Yakima Herald-Republic and The Seattle Times doggedly raised awareness, tracking PFAS contamination of water from the San Juan Islands to Spokane; reporting on its legacy use at Seattle-Tacoma International Airport; and following the State of Washington’s legal battle with the U.S. Army to clean up sites where it’s used PFAS firefighting foams in training exercises.

Photo: TC Energy

In October, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) approved expansion of the GTN Xpress natural gas pipeline, which will bring more fracked natural gas to the Pacific Northwest. The pipeline runs through Washington, Oregon, Idaho and northern California. FERC’s approval of the proposal by Calgary-based TC Energy ignited fierce opposition among state officials and residents. In November, state attorneys general in Oregon, Washington and California pressured federal energy regulators to reconsider their approval of the project.

Photo: Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy

In October, after a fiercely contested national competition, Oregon, Washington and Montana were announced as recipients of $1 billion in federal funds to build eight hydrogen production sites. The Pacific Northwest will become one of seven hydrogen hubs across the country. Advocates say hydrogen could replace natural gas to heat buildings and power trucks and ships. Production sites will include Bellingham, Centralia, East Wenatchee and Kennewick in Washington; Portland, Boardman and Baker City in Oregon; and St. Regis in Montana. According to The Seattle Times, these “nodes” will provide access to hydrogen along transportation corridors, like Interstates 5 and 90 and Interstates 82 and 84 in Central Washington and Oregon.

Ice Harbor Lock and Dam. Photo: USACE

In December, the White House released a highly anticipated agreement with states, Tribes and enviro groups to boost salmon recovery in the Lower Snake River and develop renewable energy in the Columbia River Basin. While the agreement doesn’t call for breaching four controversial dams on the river—only Congress can authorize that—it clearly supports the idea. The deal—the culmination of 22 years of conflict encompassing four different lawsuits—calls for up to $1 billion in investments along the Lower Snake River for salmon recovery and renewable energy development to replace hydropower lost from the dams. “President Biden understands that the Columbia River System is the lifeblood of the Pacific Northwest, and for the first time under his direction, federal agencies are putting all hands on deck to support regional and Tribal efforts to restore wild salmon in the region,” read the White House announcement.

Tunnel 5 Fire: Photo: Jurgenhessphotography

Just when we thought we’d gotten used to “fire season” (aka summer), May ushered in record-setting fires in western Canada—twice as bad as any other season on record—that The New York Times dubbed a “Canadian Armageddon.” By August, half of Washington and large swaths of Idaho and Oregon were blanketed by unhealthy air caused by those and other wildfires. In July, the Tunnel 5 Fire raged in the Columbia River Gorge National Scenic Area, prompting an inspection visit from Washington Gov. Jay Inslee. Throughout the summer, highways were closed and evacuations were ordered from Washington’s Okanogan County to Oregon’s Deschutes County. No story brought the West’s wildfire epidemic into sharper relief than that of 53-year-old Mary Kaneko, who lost two homes to wildfire within 10 days—one in Spokane County and one a vacation rental in Lahaina, Maui.

Dry grazing field near Klamath Falls, Oregon. Photo: Associated Press

Due to early snowmelt and lack of rain, Washington declared a drought in 12 counties while Crook County, Ore., declared a drought emergency and asked the state for disaster-relief funds … in January. So began a water-challenged year that included Seattle Public Utilities, in desert Southwest fashion, asking customers to conserve water by taking fewer showers and refrain from watering lawns. The Oregon Senate passed a historic bill in July placing strict water regulations on large livestock operations—under the bill, meat, dairy and egg farms will no longer have unlimited access to water and must submit detailed water supply plans as part of their permit applications. As reported by Oregon Capital Chronicle, Justin Iverson, a groundwater manager with the Oregon Water Resources Department, told an Oregon House Committee that if permitting rules don’t change, it’s possible up to 50,000 Oregon wells that are 50 feet below the water table or less could go dry. The water agency is seeking to update rules of the state’s 1955 Groundwater Act. Many of the Pacific Northwest’s groundwater basins are being sucked dry faster than water can be replaced.